Journal of Geomancy vol. 4 no. 3, April 1980

See end of article for source. An online document (in German) gives an overview of research at the chapel, including a criticism of Brachvogel’s work. – MB, March 2016

{8}

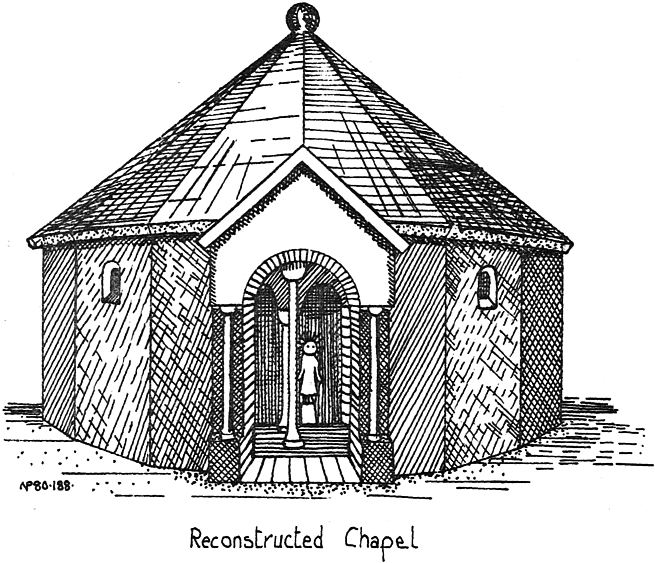

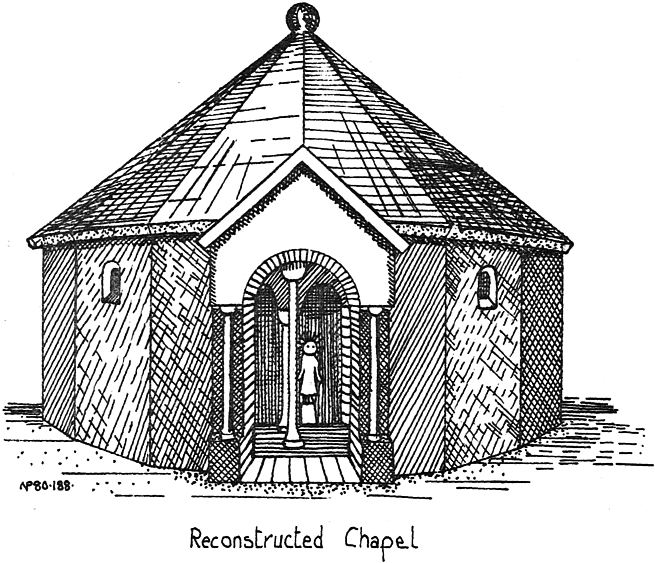

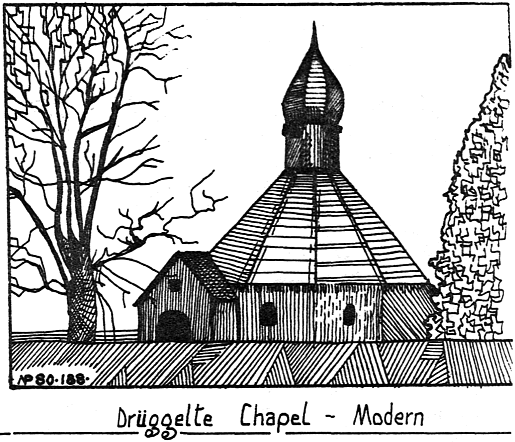

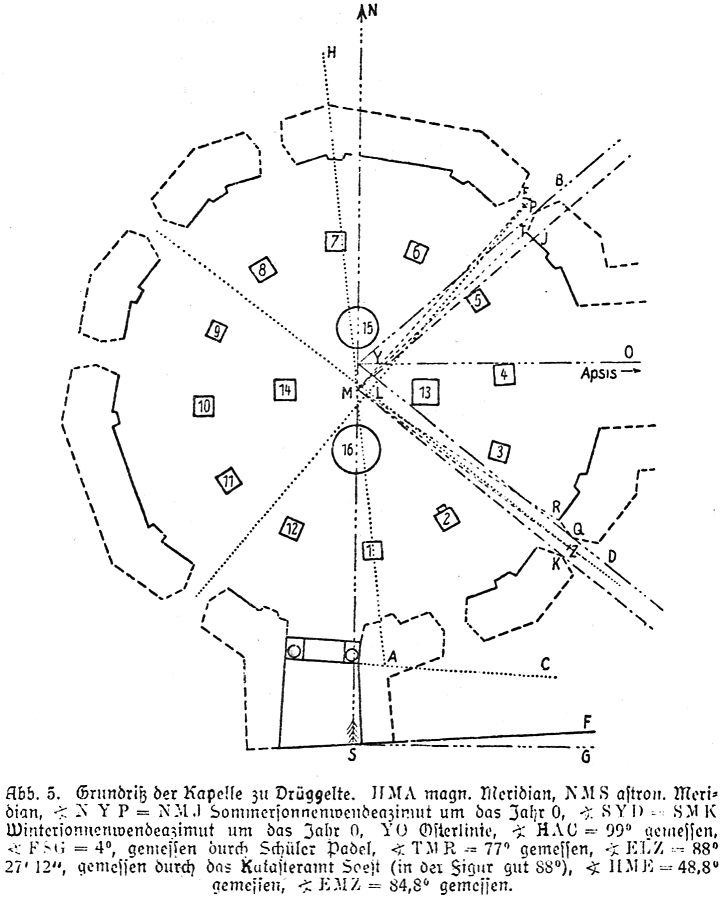

South of the beautiful old town of Soest, on top of the Haarst Mountains, lies the village of Drüggelte, consisting of a few farmhouses. In the midst of these farmhouses lies a small chapel. This was discussed by Dr W. Müller in the periodical Germanien, nos. 4 and 5, 1937. A visit was proposed and prompted me to undertake with my pupils of the Hamelin High School for Boys a survey of the groundplan of the chapel. On the basis of these measurements, which consisted almost entirely of sides of triangles, I was able to draw most of the groundplan on our return to Hamelin. The drawing included the feet of the pillars and the entrance, but only part of the surrounding walls and unfortunately not the layout of the northeast and southwest (southeast? – tr.) windows. Through my pupil Albrecht Padel, sadly killed in the Polish campaign, I had the orientation of the threshold measured. He found a 4° deviation northwards from true west. This result suggests that the N–S line goes through the two thick masonry pillars of the chapel. This was gratifying, because in the extra size of these pillars I saw a preference over the other directions, and it seemed clear that the preferred direction ought to be N–S.

That was a different result from what Dr Müller had stated. But this was not all. The above-mentioned essays expressed the opinion that the lines of sight were solsticial lines and formed a right-angled cross, i.e. were perpendicular to each other. A check showed that the solstice directions for the latitude of Drüggelte are not perpendicular; this is rather the case for higher latitudes. Thus I was compelled to disagree with Dr Müller’s statement that we are dealing here with solsticial lines; indeed I found that at best only the winter solstice line went through the SE window, while the other one met the wall.

I had the discovery of these discrepancies communicated to Dr Müller, but received the reply that he was having precise measurements taken through the official survey office of Soest. This was done, and confirmed my opinion. Dr Müller then published a new essay on the chapel, the Kleine Kostbarkeiten edited by Plotzmann, which took account of my objections, but was unable to escape from a contradiction. This contradiction I have resolved below.

Because I did not receive any report from Dr Müller direct, I decided to make in the chapel the few measurements that I lacked, and to test again the question whether or not the findings of mathematical astronomy supported the theory that we are dealing with a temple of summer and winter solstices. So far they had not done so, and this contradicted all other reasons Dr Müller could adduce that it was nonetheless a solsticial temple. I sympathized with Dr Müller’s approach, but could not agree with his conclusions.

During a holiday with my wife at Soest in the summer of 1940, I took the opportunity of obtaining, with her help, the missing measurements. I found AH (Abb. 5 – figure 5) to be the direction of the magnetic meridian. The Geophysical Institute in Potsdam informed me that the magnetic deviation for mid-1940 in the region south of Soest amounted to 6.44°. This meant that the astronomical N–S line was the line joining the midpoints of the two thick masonry pillars, as I had found previously. Angle HMN = 6.44°. On this N–S axis I then drew angles for the azimuths of the summer and winter solstices (i.e. sunrises – tr.), first from my own calculations, later, as also in this article, using values from Dr R. Müller’s graphical representation in Astronomical Orientation in Nordic–Germanic Territory, viz. for the year 0. I found once again that the summer solstice line passed south of the window B and hit the wall at J, although the winter solstice line went through the windows D. My wife and I measured the angles: HAC = 99°, TMR = 77°, HME = 48·8° and EMZ = 84,9°. Thus we were back in the situation reached by Dr Müller’s {9} work in the Kleine Kostbarkeiten, which, however, was unsatisfactory and consequently forced me to think further.

Suddenly I had a startlingly simple idea, which resolved the contradiction. I drew through P a line parallel to the summer solstice line MJ, and through Q a line parallel to the winter solstice line MK, and found that they intersected at a point Y on the N–S axis. My reason for choosing the points P and Q was that according to an old tradition the sun was supposed to shine through the window to the centre of the chapel only on St John’s Day. Therefore its rays could only just graze the south edge of the window B and the north edge of the window D. If it were to shine within the angle EMP it would reach the centre of the chapel on more than one day.

Thus the contradiction is avoided, and, for the first time, the hypothesis stated by Dr Müller in his first work, on the basis of folk traditions, etc., that we are dealing with a temple of the summer and winter solstices, is confirmed by the findings of mathematical astronomy. However, it was not at the chapel’s midpoint M that there was some kind of symbol, lit by the rising sun only at the solstices, but at Y, while the geometric midpoint M perhaps indicated the observer’s position. Y would then be the ritual midpoint. This may perhaps explain a cubical projection, about 1 metre high, carved out of the same stone as the pillar 2. For this pillar is the only one from which one can see through to Y midway between two inner pillars.

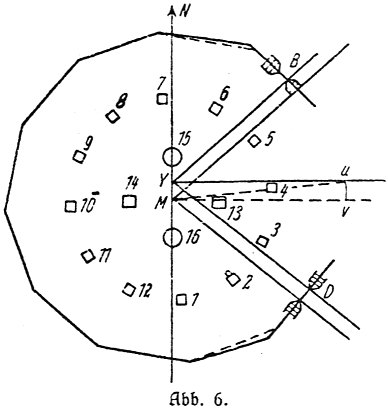

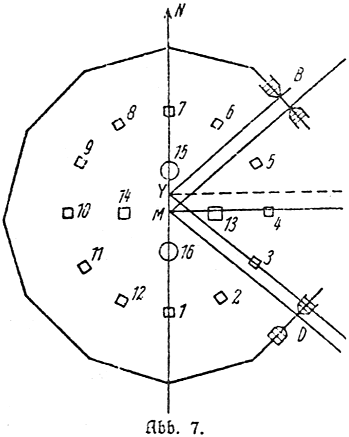

But still more. The line DY, bisecting the angle between the solstice lines, is the Easter line. It grazes across the north side of pillar 4, and thus indicates once again a grazing entry of light. And in this fact I would seek the reason why the outer colonnade is rotated anticlockwise relative to the inner one through a small angle vMu (Abb. 6). Abb. 6 & 7 (figs. 6&7) show how this comes about. In Abb. 7 the inner ring of pillars is not rotated relative to the outer. It can be seen that in this case two mutually perpendicular sight lines through the caps of the pillars are possible, much nicer than the actual sight lines emphasized by Dr Müller. The relative displacement of the two rings of pillars cannot therefore be explained by the requirement of good sightlines. The measurements of the survey bureau gave the angle ELZ between the two sight lines as 88° 27′ 12″. In my drawing ELZ turns out to be somewhat over 88°! That is good agreement.

Furthermore, Dr Müller expressed the opinion that the chapel’s present entrance could not be the original one, and gave his reasons. He states that only a detailed architectural study could make things clear. The same also applies to the chancel, which in his opinion was laid out later.

In Abb. 6 & 7 I have used a regular dodecagon for the outside plan. If in fig. 7 one draws lines from the midpoint M towards the solstices, it will be seen that the windows B and D just admit light in a grazing fashion at the solstices. Here then is no reason to rotate the outer ring of pillars. However, the Easter line would be blocked by pillar 13 and again by pillar 4, if M were the ritual midpoint.

But if I displace the Easter line the same way to the north parallel with itself, until it passes slightly to the north of both pillars, the ritual midpoint would then move northwards along the N–S axis, and now the windows B and D would no longer be correctly sited, while pillar 3 would lie on the winter solstice line. If I now turn the ring anticlockwise through the small angle uMv, then none of the holy lines comes up against a pillar. But now the outer wall must be turned round by the same amount, so that the windows allow a grazing entry of the light, and that in fact is what was done. Then in order that the window 8 shall also lie in the middle of the wall, we require a slight contraction of the wall at B. In fact, the groundplan its not a precisely regular polygon; the breadth of the wall at B measures 2·39 metres as against 2·53 metres for the next side to the north. Likewise the wall at D is only 2·39 metres wide. {10}

The condition that no holy line shall run into a pillar, and that the windows at B and D shall ensure grazing light, is fulfilled by this rotation of the outer wall and the outer ring of pillars relative to the inner ring. But then the Easter line strikes against the outer wall, in the region of a corner roughly in the centre of the altar recess. Since there exists a tradition that the temple contained a statue of the three-headed deity Triglar, one may conjecture that this stood at the point Y with one of its faces looking down each holy line. However, this is not to say that it was a Slavonic symbol; on the contrary the symbol pointing in three directions is here proved to be Germanic. Again, recent researches have deprived the Slavs of a three-headed deity. Thus e.g. Wienecke, Forschungen and Fortschritte, 1939; Schuchhardt, Vorgeschicht von Deutschland, 1934, p. 333. (In the Kleine Kostbarkeiten is an article by Walther Wust, entitled The Triple face, evidence of Aryan sun-worship. The triple face described therein doubtless represents the sun).

If I have used solstice azimuths for the year 0, this should not be taken to imply a precise dating. Since the azimuths are constantly, though very slowly, changing, this implies a motion of the point Y along the N–S axis. The chapel could thus be used for a long time as a temple of the solstices and the equinox (Easter); for the motion of Y is only very slight. Besides, the purpose could be maintained by small alterations to the edges of the windows.

For a determination of the age, a knowledge of the exact position of Y and of the solstice lines actually used would be needed; and also modifications to the azimuths required by the profile of the horizon would have to be taken account of. But the precise layout of the oldest solsticial lines and the point Y is not known. Therefore, a dating by astronomical methods is not possible.

Originally published in Mannus 34, p. 115–122, 1942.

Translated by Michael Behrend, March 1980, edited by Nigel Pennick.