Journal of Geomancy vol. 3 no. 4, July 1979

{91}

WODEN’S SWASTIKA

Nigel Pennick

Although the swastika is one of the most ancient and venerable of symbols, its recent association with German National

Socialism has rendered research into it somewhat taboo. However, serious students of prehistory recognize that recent

uses or misuses of symbols have only a superficial bearing on the correct interpretation of ancient usages.

The present article was prompted by a graffito brought to the author’s attention in the church at Sutton in

Bedfordshire. The inscription in question is medieval in date and thus long after the suppression of paganism in

England, and of course is inside a Christian building. The graffito is of a bearded man with flowing long hair

performing what is perhaps a dance. One hand is upraised and in form resembles the carvings of hands which adorn the

walls of the Royston Cave in Hertfordshire. Upon his coat is a swastika of a very precise type. This swastika pattern

would appear to be a decorative variation on the familiar heraldic/religious symbol which occurred everywhere from Roman

mosaics through Victorian stained-glass, British World War One savings stamps to the Nuremberg Rallies and pro-Communist

Vietnamese Cao Dai shrines. However, research has shown that this variation of the emblem was not a fanciful doodle made

by a bored pagan during a compulsory church service. Although it adorns a Christian medieval wall, the symbol traces

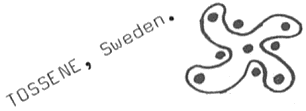

back to prehistoric times in both Britain and Scandinavia. In the nineteenth-century book by Holmberg,

Skandinaviens Hällristningar, an identical swastika is illustrated on plate 32. The

Hällristningar, rock scribings of prehistoric date found all over Scandinavia, comprise a series of as yet

inexplicable symbols which may have had a religious meaning, may have been writing, calendrical notation, magical

invocation or divinatory purpose. What is known about these enigmatic graffiti which occur upon stones, rock faces and

in caves, is that they are the direct forerunner of the magical system of writing known as Runic (see the author’s

Ogham and Runic, available through IGR). The symbol in question was found at Tossene on the coast of Sweden

to the north of Göteborg.

The present article was prompted by a graffito brought to the author’s attention in the church at Sutton in

Bedfordshire. The inscription in question is medieval in date and thus long after the suppression of paganism in

England, and of course is inside a Christian building. The graffito is of a bearded man with flowing long hair

performing what is perhaps a dance. One hand is upraised and in form resembles the carvings of hands which adorn the

walls of the Royston Cave in Hertfordshire. Upon his coat is a swastika of a very precise type. This swastika pattern

would appear to be a decorative variation on the familiar heraldic/religious symbol which occurred everywhere from Roman

mosaics through Victorian stained-glass, British World War One savings stamps to the Nuremberg Rallies and pro-Communist

Vietnamese Cao Dai shrines. However, research has shown that this variation of the emblem was not a fanciful doodle made

by a bored pagan during a compulsory church service. Although it adorns a Christian medieval wall, the symbol traces

back to prehistoric times in both Britain and Scandinavia. In the nineteenth-century book by Holmberg,

Skandinaviens Hällristningar, an identical swastika is illustrated on plate 32. The

Hällristningar, rock scribings of prehistoric date found all over Scandinavia, comprise a series of as yet

inexplicable symbols which may have had a religious meaning, may have been writing, calendrical notation, magical

invocation or divinatory purpose. What is known about these enigmatic graffiti which occur upon stones, rock faces and

in caves, is that they are the direct forerunner of the magical system of writing known as Runic (see the author’s

Ogham and Runic, available through IGR). The symbol in question was found at Tossene on the coast of Sweden

to the north of Göteborg.

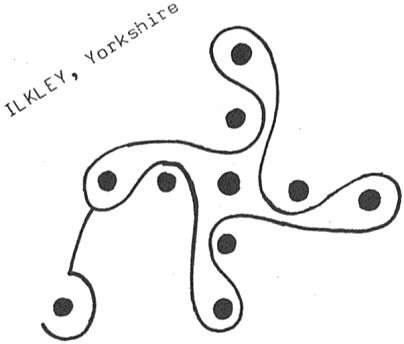

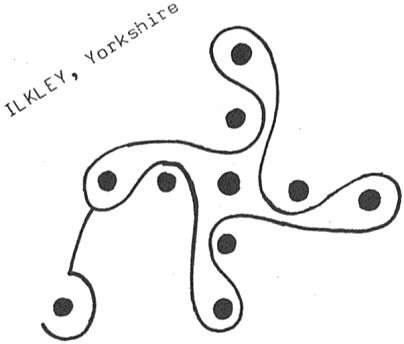

However, the British connexion is not restricted to the pagan dancer at Sutton. On a prehistoric rock near Ilkley in

Yorkshire was found another, identical swastika.

J. Romilly Allen, the Victorian antiquary and expert on ancient

Celtic art, wrote: “About a mile to the west of the Panorama Rock, on the extreme edge of the cliff forming

the north boundary of Addingham high moor, and overhanging the valley of the Wharfe, is a large block of gritstone

19 ft. long by 7 ft. broad, by 4 ft. 6 ins. thick. At the east end of the stone are two rock basins

1 ft 3 ins, across, and at the other is carved the very unusual device shown on the accompanying drawing (the

swastika). I consider this to be by far the most interesting of all the Ilkley sculptures … The

“swastica” occurs on the foot of Buddha … and the Ilkley device appears to be a modification made by

doubling the lines and curving the arms. The “swastica” was engraved on a very large number of the spindle

whorls found by Dr. Schliemann at Troy. The “swastica” or “fyllot”

is said to be a symbol for Baal or Woden.”

This last piece of information is of the greatest importance. Its connexion with pagan religion, a survival in folk

customs long after the Christian religion had been imposed on an unwilling audience by the state, explains the identity

of the symbol in ancient and historic times.

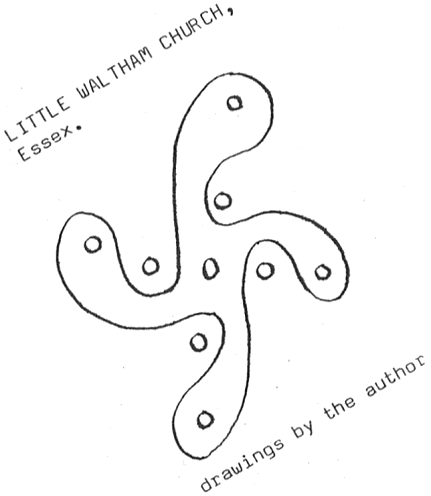

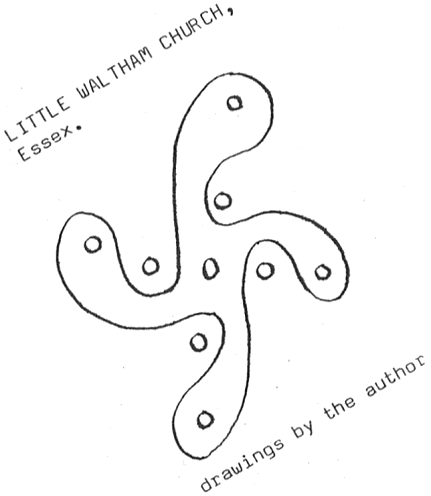

In Little Waltham church in Essex, the symbol again appears, this time without the dancer.

The standard form of swastika has been equated with the summation of the four seasons, the positions of the circumpolar

stars known now as the Plough or Great Bear, a constellation of the utmost significance since the time of Ancient Egypt.

It was this constellation which provided the orientation-point for Egyptian temples, and was known as the

{92}

time as the Bull’s Foreleg. This leg connexion can still be seen in the three legged swastika or

triskele which forms the national emblem of the Isle of Man.

The emblematical nature of ancient knowledge is nowadays often misunderstood. Just as the constellations of the heavens

are still used and form a valuable mnemonic for recalling star names and positions, so much of the ancients’

figurative names for terrestrial and celestial phenomena was also not to be taken literally, as modern pundits do almost

invariably. Earth energies were personified as dragons or Yarthlings; Devas, spirits, fairies, gremlins, gnomes, angels,

‘Black Shuck’, ‘Wills’ Mother’s’, Miles’s Boy, Old Nick, The Wild Hunt and

other such folk-memories may be a way of explaining or describing forces and energies which are of this type. Research

into such matters is only now being freed from the deadhand of Victorian materialism which has hindered it by banal

literal acceptance.

To return to the pattern. Is there any clue now available to us for its interpretation? The answer is yes. Current about

the beginning of this century was a certain piece of lore well known to schoolboys. It was couched in the terms of a

puzzle of the kind which required a pictorial solution like the Königsberg Bridge Problem or the Gas/Water/

Electricity to three houses trick. These two are insoluble, but the following is not: “Four rich men and four poor

men had their houses symmetrically situated at the corners of two squares, one inside the other, with a pond in the

centre. The rich men determined to build a wall which should exclude the poor men, who had their houses close to the

water, from the use of it, and at the same time permit the rich men free access, as before. How was this done?”

It was done by the swastika pattern of Sutton. This riddle has the makings of a degenerate legend or a mnemonic

exercise. Its potency as a symbol certainly survived not only the

{93}

Christianization of England but even its known function and meaning. In geomantic terms it appears to symbolize the

central axis of the universe with its circulating forces. The eight dots around the world axis or omphalos

may refer to the prechristian eightfold division of the year (and the day) still observed by pagans: Autumnal Equinox;

Samhain; Winter Solstice; Candlemas; Spring Equinox; Beltane (May Day); Midsummer Solstice and Lammas. An article in a

later issue of JOG will deal more fully with the eightfold division of space and time in pagan England. The swastika of

Sutton was obviously a symbol worn on a garment of a dancer sacred to Woden or Baal (Bel, Celtic god of light). Does

this graffito represent a May dancer or the spiritual forerunner of Morris Dancers? Future research into

astronomical/geomantic symbolism may yet reveal the true meaning of this enigmatic emblem.

If any reader has any information on other examples of this symbol, I would be grateful to hear from them.

The present article was prompted by a graffito brought to the author’s attention in the church at Sutton in

Bedfordshire. The inscription in question is medieval in date and thus long after the suppression of paganism in

England, and of course is inside a Christian building. The graffito is of a bearded man with flowing long hair

performing what is perhaps a dance. One hand is upraised and in form resembles the carvings of hands which adorn the

walls of the Royston Cave in Hertfordshire. Upon his coat is a swastika of a very precise type. This swastika pattern

would appear to be a decorative variation on the familiar heraldic/religious symbol which occurred everywhere from Roman

mosaics through Victorian stained-glass, British World War One savings stamps to the Nuremberg Rallies and pro-Communist

Vietnamese Cao Dai shrines. However, research has shown that this variation of the emblem was not a fanciful doodle made

by a bored pagan during a compulsory church service. Although it adorns a Christian medieval wall, the symbol traces

back to prehistoric times in both Britain and Scandinavia. In the nineteenth-century book by Holmberg,

Skandinaviens Hällristningar, an identical swastika is illustrated on plate 32. The

Hällristningar, rock scribings of prehistoric date found all over Scandinavia, comprise a series of as yet

inexplicable symbols which may have had a religious meaning, may have been writing, calendrical notation, magical

invocation or divinatory purpose. What is known about these enigmatic graffiti which occur upon stones, rock faces and

in caves, is that they are the direct forerunner of the magical system of writing known as Runic (see the author’s

Ogham and Runic, available through IGR). The symbol in question was found at Tossene on the coast of Sweden

to the north of Göteborg.

The present article was prompted by a graffito brought to the author’s attention in the church at Sutton in

Bedfordshire. The inscription in question is medieval in date and thus long after the suppression of paganism in

England, and of course is inside a Christian building. The graffito is of a bearded man with flowing long hair

performing what is perhaps a dance. One hand is upraised and in form resembles the carvings of hands which adorn the

walls of the Royston Cave in Hertfordshire. Upon his coat is a swastika of a very precise type. This swastika pattern

would appear to be a decorative variation on the familiar heraldic/religious symbol which occurred everywhere from Roman

mosaics through Victorian stained-glass, British World War One savings stamps to the Nuremberg Rallies and pro-Communist

Vietnamese Cao Dai shrines. However, research has shown that this variation of the emblem was not a fanciful doodle made

by a bored pagan during a compulsory church service. Although it adorns a Christian medieval wall, the symbol traces

back to prehistoric times in both Britain and Scandinavia. In the nineteenth-century book by Holmberg,

Skandinaviens Hällristningar, an identical swastika is illustrated on plate 32. The

Hällristningar, rock scribings of prehistoric date found all over Scandinavia, comprise a series of as yet

inexplicable symbols which may have had a religious meaning, may have been writing, calendrical notation, magical

invocation or divinatory purpose. What is known about these enigmatic graffiti which occur upon stones, rock faces and

in caves, is that they are the direct forerunner of the magical system of writing known as Runic (see the author’s

Ogham and Runic, available through IGR). The symbol in question was found at Tossene on the coast of Sweden

to the north of Göteborg.