Journal of Geomancy vol. 3 no. 2, January 1979

{31}

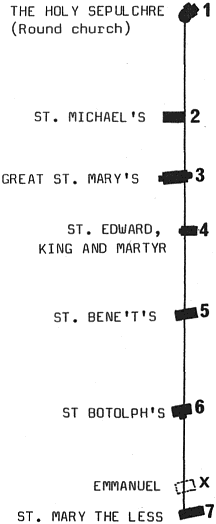

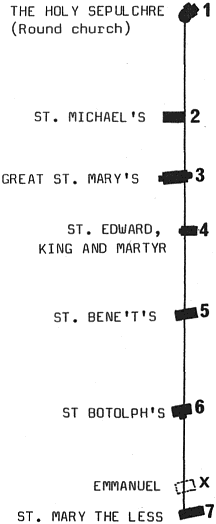

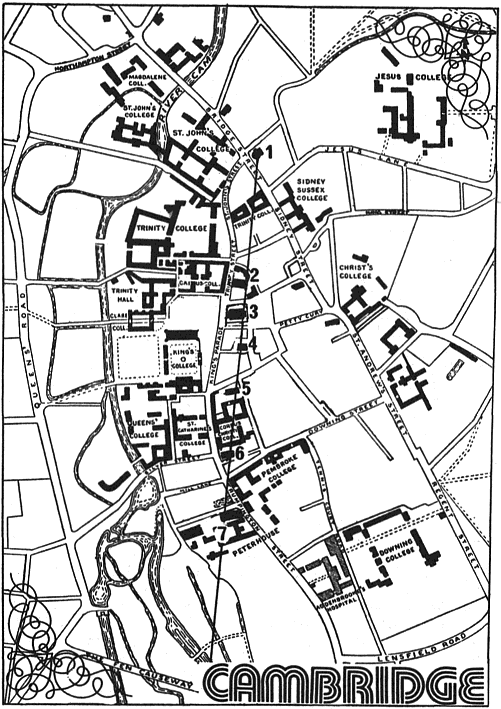

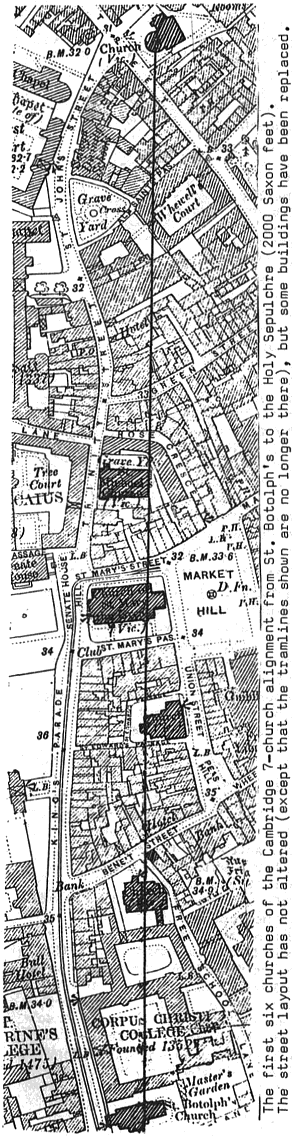

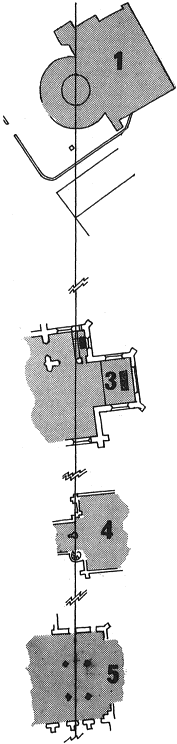

Since the rediscovery of aligned sites by William H. Black and the formulation of a coherent theory of alignments by Alfred Watkins, the bane of ley research has been accuracy. Mathematicians can put forward randomness tests and discern the likelihood of an alignment being chance or designed, but, owing to the large scales involved, it is rarely possible to state with a great degree of accuracy the exact position which a ley line passes through any building placed upon it. This difficulty is of course most pronounced in long alignments in country districts where large-scale plans are difficult to obtain, if indeed they actually exist. In cities, however, the Ordnance Survey have been busy, and extremely accurate maps and even plans have been made of them. Cambridge is one such city, and it possesses a remarkable {32} ley comprising no fewer than seven pre-reformation (and some pre-conquest) sites, the site of one of the gates of the medieval city and several other ‘pointers’. This ley was first noticed by Nigel Pennick in 1967, and was first mentioned in Cambridge Voice series 2 number 4, 1970, on a front cover feature. Its shortness (3000 feet) and existence in a single town makes it an admirable ley for close study, and this report is the result of detailed work both in the field and on maps up to 1:500 scale (OS circa 1886). The ley is of special interest because of its connexion with the Holy Sepulchre church, one of the few remaining round churches of the Knights Templar. The ley starts exactly at the centre of the rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre, at the point where the altar would have stood in Templar days, making the line a radial. The church is one of those based on the octagon, but the ley does not pass through the centre of one of the eight pillars, though it does pass through the more westerly of the two southern pillars. Passing through a wall, not a window, the ley crosses the graveyard towards Bridge Street, and cuts through the corner of a secular building, probably an ancient boundary, as the shops which now exist there are reconstructions of buildings dating back to at least the seventeenth century and maybe earlier. Across Bridge Street, it passes through several buildings including the Flying Stag, at present the home of Glyn Daniel, Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge University and staunch opponent of geomancy.

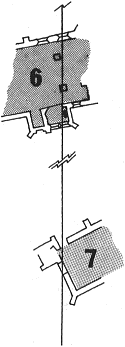

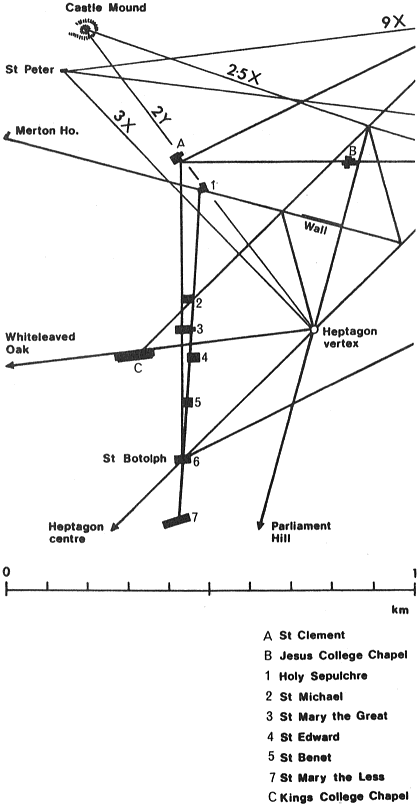

For several hundred yards the line crosses through various buildings and cuts All Saints Passage, Green Street and Rose Crescent. Beyond the crossing with Rose Crescent is St. Michael’s church, the only church on this line which no longer has regular Sunday services. The nave of the church was turned into a hall over ten years ago, and is totally desacralized, being used for jumble sales, Open University events and other profane happenings. The eastern end is still retained for worship, and the ley runs across the eastern end, outside the wall, through the buttresses. The east wall is exactly parallel with the line, which must have therefore determined the orientation of the whole church. Lines parallel with walls have an archaeologically-determined precedent – the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico, where a star-alignment is sighted along the outside of a wall (Horst Hartung, Die Zeremonialzentren der Maya, Graz, 1971). The church building is linked into the ley through the buttresses, so there is actual contact. From the centre of the round church to the axis of St. Michael’s is 886·5 English feet, 806·8 Saxon feet. The latter measure will be quoted throughout, as it appears to be significant in the laying-out of the line. From St. Michael’s (illustration 2 shows the east end in Caius College), the ley crosses through W.H. Smith’s book and magazine shop, across St. Marys’s Street, and into the church of Great St. Mary’s. This church is the so-called University Church, the place where official services for the University are held. It is the largest church on this alignment, and a circle cut in the southern buttress of the door at the west end (not on this line) is taken as the centre of the city of Cambridge, the point from which all distances from Cambridge are measured. Add to this the uncanny elevation of its incumbents to the status of Bishop, and the importance of the site may be gauged.

The line enters Great St. Mary’s along the edge of a small priest’s door on the north side of the St. Andrew’s Chapel. This is now blocked, and the site of an aumbry which, from the light burning above it, holds the reserved sacrament. This chapel is the venue for evening prayers each night at 6 pm. From the centre of the Holy Sepulchre church to the priest’s station before the altar of the St. Andrew’s chapel is 1002 Saxon feet – surely a significant distance, as further evidence will prove. The ley touches a pillar’s edge on leaving the St. Andrew’s chapel, crosses the chancel, the south chapel, and passes out of the church by means of a window. The ley then crosses the southern part of the churchyard, St. Mary’s Passage, and various buildings before entering the churchyard of St. Edward, King and Martyr. The ley penetrates the corner of the west end of St. Edward’s, travels through the staircase of the turret and leaves for the next site on its path – Bene’t’s. Before reaching St. Bene’t’s (St. Benedict’s to be precise), the ley touches the corner of the medieval Friar’s House, now a fancy goods shop, at the entrance to Free School Lane.

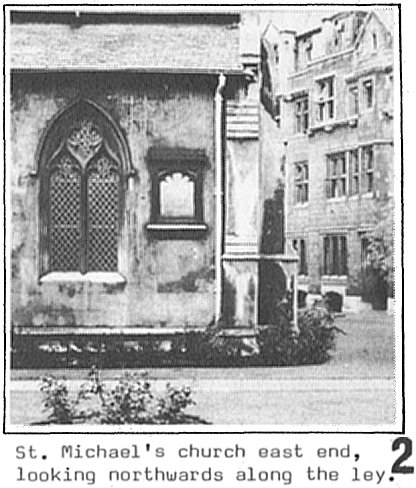

St. Bene’t’s is the oldest church in the city, having a Saxon tower dated to c. 1020. The ley enters through <a> wall and leaves just cutting the edge of a window. It misses the central pillars of the church. After St. Bene’t’s, the ley crosses Corpus Christi college before entering St. Botolph’s, which it enters by a window, passing through {33} the central panel of the three-panelled window. In the nave it crosses the radius of the landscape geometry heptagon (see Landscape Geometry of Southern Britain, IGR). The distance of this crossing from the Holy Sepulchre centre is 2162·8 English feet, 1968·3 Saxon feet. The ley then cuts directly through the centre of a pillar on the south side of the nave, cuts the edge of the wall at the entrance to the Holy Trinity chapel, and crosses in front of the altar of that chapel. Again, just as in the St. Andrew’s chapel of Great St. Mary’s, the line exactly passes in front of the altar, directly over the priest’s station at the position in which he would celebrate the Mass. The distance from the centre of the Holy Sepulchre is 1998 Saxon Feet. With an error of 0.2%, the centre of the round church is thus 1000 Saxon feet from the St. Andrew’s Chapel and 2000 feet from the priest’s station in the Holy Trinity chapel. Such a periodicity on an alignment is surely an indication of some important, if lost, practice, perhaps of activating the line by saying mass (or some other ritual formula) at fixed distances along it simultaneously. The ley leaves St. Botolph’s by a window, crosses Botolph Lane and goes through some buildings before emerging exactly through the corner of what is now the Penguin Bookshop. At this point, the ley traverses the junction of King’s Parade, Trumpington Street and Pembroke Street, the site of the erstwhile Trumpington Gate of the medieval city of Cambridge, the point where the artificial watercourse known as the King’s Ditch formerly crossed the road – an important point in the geomancy of any city, being the access point of spiritual as well as secular and military friends and foes alike. After the Trumpington Gate site, ley enters relatively modern buildings before passing through a Victorian church – the Emmanuel {34} United Reformed Church (formerly Congregational). The significance of nineteenth-century churches on ley lines remains enigmatic, but just a little further south is the medieval church of St. Mary the Less (formerly dedicated to St. Peter, the same dedication as a small, now redundant, church on the other side of the river in the Borough – the old Roman town). The ley entered St. Mary’s by a door, now blocked, and left by a window in the west end of the church. It was rebuilt drastically during the last century, and the whole of the west end now bears little resemblance to the former layout. However, the reconstructors saw fit to insert fragments of a pre-conquest stone cross in the wall at the point where the ley leaves the southern side of the church.

From St. Mary’s the line has been traced as far as the south coast. It passes 20 metres to the east of the former Trumpington mound, which has since been erased from both reality and the Ordnance Survey maps. It also misses the Thriplow tumulus by 25 m, this time, to the west.

The most important site which the ley traverses is the Palace of the Bishops of London at Much Hadham. The Bishops were bequeathed the manor in 950, so the present 16th century building may well be on the site of the former Saxon manor. The Saxon connexion is continued!

The ley crosses nothing else of any significance between Much Hadham and the south coast.

The ley is characterized by the following: Mainly within the precincts of the old City of Cambridge, it passes exactly through the centre of the round nave of the Holy Sepulchre Church. The east wall of St. Michael’s Church is exactly parallel to the line. It passes through two side chapels, both of which are still in use, crossing the priest’s station at each one. The separation of the centre of the round church and the two priests’ stations is 1000 Saxon Feet. There are 7 pre-reformation churches in the line, 1 post-reformation church, 3 corners of buildings, 2 road junctions, and the site of a city gate, all within 3000 English feet. Carried southwards, the line crosses no other significant pre-reformation site except the Palace of the Bishops of London.

The above points indicate a high degree of deliberation in the layout of this ley. Its azimuth, 4.31° east of true north, precludes any solar or lunar orientation, and foils any attempt to date it on astroarchaeological evidence.

It is often stated, sometimes on flimsy evidence, that leys tend to pass through walls by means of windows, doors, squints and other apertures. In this ley, we are able to analyze precisely (ie. correct to within 1 foot; 30 cm) the entry-points of the ley into the churches. Of potential ‘walls’, the line penetrates 6 whilst passing through 9 apertures. Of potential ‘pillars’ within churches, it hits 2 and misses 3.

The dating of the ley by astronomical evidence, which is the usual procedure for astroarchaeologists working on American or megalithic sites, is not possible.

The Saxon metrology (table below), points to a Saxon origin of the churches on the ley, yet the history of the city shows that it was not only Saxon but also Danish until the 11th century. In 875, the Danish navy wintered at Grantabrycge (as Cambridge was then called), and three years later it passed into the hands of the Danelaw officially under the provisions of the Treaty of Wedmore. It remained a Danish town – an important seaport, as the river was navigable from the Wash – with its dock area around the Holm, an area where St. Clement’s church now stands, just to the north of the Holy Sepulchre. In the year 1010, the town was burnt down, and the oldest surviving building, St.Bene’t, dates from the rebuilding of Cambridge at that period. Because of the destruction of 1010, nothing predating this exists. {35}

However, we have the problem of the Saxon feet. This is not so much a problem when it is remembered that the English foot was not instituted until an edict of king Edward I in 1305. Even then, he did not alter land measure, which remains to this day (barring metrication) based upon the Saxon foot. The fundamental measure was the Rod, which equalled 15 Saxon feet. Edward made the now English foot fit the Rod – 16½ of them. Thus the mile remained the same, being 5280 English feet instead of 4800 Saxon feet. As the Saxon foot was in current use until at least 1305, it tallies with the official estimate that the churches of Cambridge were all built by 1280, mostly in the 12th and early part of the 13th century.

The origin-point of the ley, the Holy Sepulchre, dates from between 1114 and 1130. It was built upon a pre-existing sacred site, the Churchyard of St. George. As a dragon-slaying saint, St. George is admirable as a dedication for an omphalos, as the Holy Sepulchre is a microcosm of the world, the centre of its rotunda being the omphalos about which rotates the flat circular earth (in medieval cosmology).

In Saxon feet, the ley analyzes as follows:

| Holy Sepulchre | centre | 0 | ·0 SF |

| St Michael’s | N.wall | 781 | ·0 |

| „ | Axis | 806 | ·8 |

| „ | S.wall | 832 | ·6 |

| Gt St Mary’s | N.wall | 991 | ·0 |

| „ | Priest’s stn. | 1002 | ·0 |

| „ | Axis | 1024 | ·6 |

| „ | S.wall | 1058 | ·1 |

| St Edward’s | NW corner | 1233 | ·6 |

| „ | staircase wall | 1267 | ·1 |

| St Bene’t’s | N.wall | 1540 | ·1 |

| „ | S.wall | 1595 | ·9 |

| St Botolph’s | N. wall | 1951 | ·0 |

| „ | Heptagon R. | 1968 | ·3 |

| „ | Priest’s stn. | 1998 | ·0 |

| „ | S.wall | 2004 | ·7 |

| Lt St Mary’s | N. wall | 2708 | ·8 |

| „ | Axis | 2726 | ·2 |

| „ | S.wall | 2743 | ·1 |

correct to 1 SF.

The ley ties in with the landscape geometry of the city (see diagram on right), which links the city churches and chapels with the rest of the country. The 7-church ley, and the 6-church ley, both of which have 5 churches in common, have a precise relationship to the heptagon, which defines the orientation of King’s College Chapel with relation to the Whiteleaved Oak, an important geomantic centre at the junctions of the counties of Hereford, Worcester and Gloucester (now officially abolished for bureaucratic reasons). Parliament Hill, an ancient holy site associated by some writers with ancient Druidic rites, and the Gogmagog Hill Figures are on projections of various alignments in the city of Cambridge, inferring that either the alignments are part of a very ancient survey system whose knowledge was perpetuated into mediaeval times, or that they are part of some earth energy system, naturally divined by those who had need to use it.

The use of pre-Edwardian measure in the ley, but post-megalithic dimensions infers a date around the millennium for the completed system. As most of the churches are later, it could be taken as evidence for a twelfth or thirteenth-century alignment. The laying-out of Salisbury Cathedral may indicate the survival of a former science {36} of surveying whose accuracy has been underestimated by modern historians. When the activities of the military garrison at Old Sarum became too troublesome for the clergy of the cathedral which also occupied the ancient earthwork, they decided to move the cathedral to a new site. Legend recounts how an arrow was shot from the ramparts and the cathedral’s new site was defined by the place of the arrow’s fall. However, the cathedral of Salisbury (or New Sarum) is on the alignment from Stonehenge to Clearbury Ring, which is surely of far more ancient provenance than the 1220 cathedral. The reference to the arrow may provide the key. In the late middle ages, the baculum or Jacob’s Staff was often called the ‘crossbow’ because of its superficial resemblance to that weapon. The untutored townspeople, observing the surveyors’ visit to Old Sarum in late 1219, may have mistaken the instruments for the weapon and given rise to the folk-tale. The alternative idea of chance, so gaily trotted out by the orthodox, is untenable in the face of the evidence. In the early 13th century, the system of measurement would have been in subdivisions of miles – furlongs, rods and saxon feet, the measure used in the 7 church ley in Cambridge.

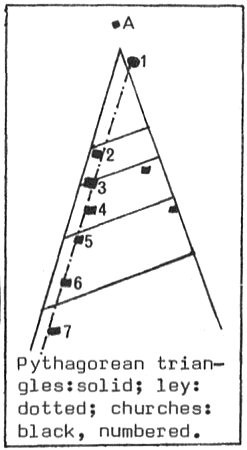

In the book Megalithic Software I, the Borsts list Cambridge as a ‘triangular town’. The diagram below is redrawn from the Borsts’ on p. 106. The small scale of their plan makes it difficult to reproduce accurately, but it appears that their hypotenuse line is parallel with the 7 church ley. The thesis of Megalithic Software is that the remains of former megalithic-period layout still underlies many cathedrals and cities in Britain. Cambridge is supposed to show in its general layout a number of 3,4,5 Pythagorean triangles, with moduli of 40, 70, 100, 140,and 200 Megalithic Yards. The apex of this triangle is between the Holy Sepulchre and St. Clement’s church, at approximately the position of the Mitre public house. The bases of the triangles form Green Street, Market Street, Bene’t Street and Downing/Pembroke Street. The hypotenuse appears to be parallel with the 7-church ley, so why did the Borsts choose a line to the west of this – perhaps because it coincides with part of St. John’s Street, and makes the triangles integral in megalithic yards. The Borsts admit that the geometry is probably not megalithic in age as a much more ingenious pattern of triangles would be expected.

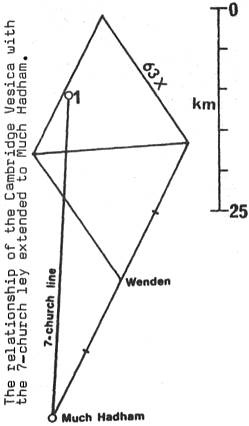

Finally, the 7-church ley’s extension to Much Hadham crosses an extension of the southeast side of the Cambridge Vesica at a point equal in length from the apex of the vesica to the side = 63x units.

..................................................

TEXT BY NIGEL PENNICK: CALCULATIONS BY MICHAEL BEHREND

..................................................

Behrend, M: The Landscape Geometry of Southern Britain. IGR Occasional Paper No. 1 (1975, repr.1976,1978).

Behrend, M: The Geometry of Cambridge in The Geomancy of Cambridge (Pennick ed.), IGR (1977).

Borst, L.B., & Borst, H.M.: Megalithic Software I, New York, (1975).

Hartung,H.: Die Zeremonialzentren der Maya, Graz (1971)

Pennick, N.: The Cambridge 7-church Ley, Arcana 5 (1973)