Journal of Geomancy vol. 1 no. 4, July 1977

First published in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 35, 368–371 (1879), and reprinted in Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, Series 1, 4, 537–540 (1880). A PDF of the reprint can be viewed free of charge through the Archaeology Data Service. For better quality, the image below was scanned direct from the JBAA rather than from the JoG. – MB, March 2015

{82}

This remarkable, though little known, megalithic monument is situated at Gunnerkeld*, a mile and a half north of Shap, in Westmorland, and four or five hundred yards off the Appleby Road, where it crosses a hollow three-quarters of a mile east of the point at which that road leaves the one from Shap to Penrith. The site is in the midst of a valley dipping towards the north-north-west, on a low, grassy tongue formed by a gentle depression on one side, and a little wady** on the other. It is on the border of a region fertile in prehistoric antiquities beyond most others in Britain. A mile to the south of Shap, the remains of a fine megalithic circle may be seen close to the fence of the railway which has swept away the larger part. Proceeding northward, close to the village, are the relics of what must once have been a grand parallelithon, second only, among our insular antiquities, to those at Avebury, and trending toward two massive boulders a furlong apart, – the farthest called THUNDER STONE, – which lie on rising ground about a mile to the north-west. In another direction, a mile to the east of Shap church, poised on a brow of rock, is a third boulder which, though it may have been placed there by human hands, is much more likely to be a bloc perché, for reasons to be presently given. The chain of heights bounding the Shap valley on the east, crowned by tumuli alternating with stone circles and a British camp, looks down into a group of inclosures, regarded as the remains of aboriginal settlements, which are scattered over the lower slopes on the other side.

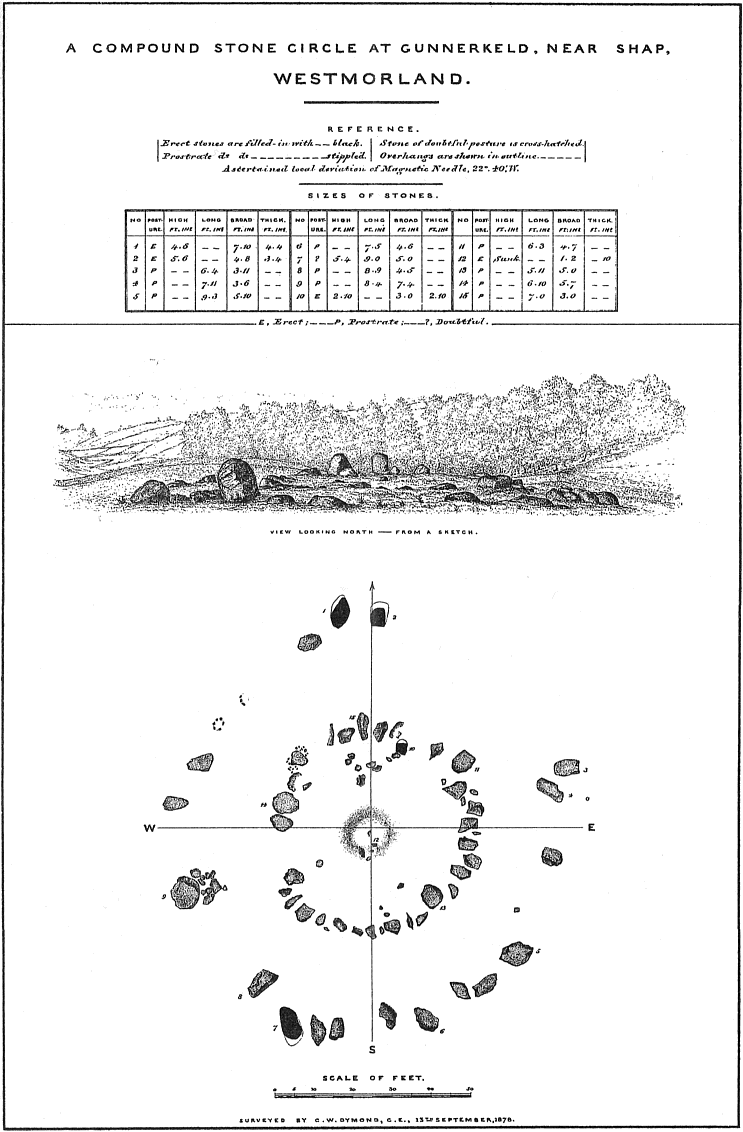

The plan, of which the accompanying illustrative Plate is a reduced fac-simile, has been laid down with the utmost care from elaborate measurements. The local deviation of the compass was deduced from repeated special observations made in the district, – the needle being found to be influenced by circumstances which made this precaution necessary.

So far as my researches have extended, no plan of this megalithic group has hitherto been published; nor, save in a local guidebook, have I ever seen it mentioned. It belongs to a class of which there are but few examples in Britain — a class characterized by concentric monolithic rings. Yet it is not quite unique even in its own district; for, while exploring the fells at the distance of three miles and a half, I found another executed on a similar plan, of which the principal points are noted below***.

*In local parlance this word simply means ‘sportsman’s spring’.

It should properly be Gunner’s Keld; but the possessive s

is usually dropped by the people of the north-west country.

**There is no English equivalent.

***¼ mile south of Oddendale, 2½ miles SE of Shap. 2 concentric rings,

outer ring 86 feet in diameter, 27 stones; inner 23 feet in diameter, 23

stones.

{83}

The outer ring of Gunnerkeld circle (if it may so be called) is 106 feet in diameter from north to south, and 97 feet from east to west. It consists at present of 18 large stones, all prostrate*, except two at the north point, which form a fine pylon. The seats of two more which have been removed are distinctly visible on the north-west side; and large gaps indicate that several others also (perhaps as many as 8 or 10) have probably disappeared. In front of No. 9 there is a group of weather-worn stones lying loose on the ground in a manner that gives no clue to their original arrangement. The inner ring – 52 feet in diameter from north to south, 48 feet from east to west, and nearly concentric with the outer one – has, exclusive of five or six fragments, 30 stones, generally of smaller size than those composing the outer ring. All of them are prostrate, and the number nearly complete; for there is only room for three, or perhaps, four more in the small gaps that interrupt the continuity of the ring. Within its northern arc, eight stones – most of them lying loosely on the surface, and all, save one, small and prostrate, are segmentally ranged. Their intent can only be conjectured, as there is no disturbance of the ground in the area which they inclose, to indicate that it may have been devoted to separate sepulture. A few other fragments are dispersed over the floor of the inner circle, in the centre of which is a pit, evidently made by the rifling of one or more graves. A stone, No. 12, small, flat, and thick, its top level with the surface of the ground, remains rooted in situ at the southern edge of the pit. It was, doubtless, one of the side or end stones of a destroyed cist. The question arises, with respect to the prostrate stones,were they originally erect, and have they been overthrown? I have no hesitation in expressing my belief that they were never set up on end; and if so, these rings are of a type differing, perhaps of set purpose, from the true peristalith.

No. 7, the giant of the group,and a few smaller stones, are red granite. The remainder appear, for the most part, to be composed of igneous or metamorphic rock of various structure. The rock of the site is a thin-bedded Carboniferous limestone; but, to one who has taken note of the immediate surroundings, and has walked over the limestone heights toward the south, the source from whence these large blocks were obtained is evident. Every wall in the neighbourhood is mainly built of similar stone; and boulders of red granite are sprinkled by thousands on the uplands to the east of Shap, several miles away from the mountain-beds from which they were torn, and within comparatively easy reach of Gunnerkeld. This extensive local occurrence of erratic blocks deepens into conviction a conjecture which I entertained when surveying Long Meg and Her Daughters, that the stones there seen were not transported by human agency, but were found on the spot. The closest scrutiny has not revealed the existence of artificial marks on any of the stones at Gunnerkeld.

Much of the ground inclosed by the concentric rings has been somewhat disturbed. The floor of the inner area is slightly higher than that of the surrounding annular space; and there can be no doubt that it was a stone-cinctured sepulchral barrow. The purpose of the outer ring is not so evident. Emphasized as it is by the pylon, it suggests processional observances. At the same time we find the Oddendale circle wanting in that prominent feature which is the main support of such an idea. The position of the gateway and of the segmental chamber may be compared with those in the Keswick circle.

*One stone, No. 7 on the plan, is therein marked as doubtful; but, although in the view it has the appearance of being erect, its height and breadth are nearly equal, while its horizontal length is much greater than either. It should, therefore, properly be classed among the prostrate stones.