Journal of Geomancy vol. 1 no. 1, October 1976

{1}

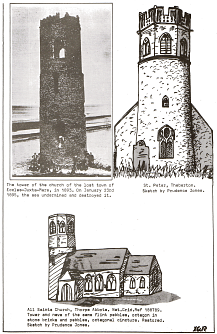

The counties of Norfolk and Suffolk are dotted with old churches of a remarkable design: 14th and 15th century naves having a west tower that is round and Norman at the base, octagonal and 14th century or so at the upper stage(s). Although there are a few octagonal towers in the rest of the country, such as those on a square base at Uffington in Berkshire and Doulting in Somerset, and the completely octagonal ones at Coxwold (Yorks.), Stanwick (Northants.) and Standlake (Oxf.), this particular design of round Norman (or pre-Conquest) base with later octagonal upper lantern is peculiar to East Anglia.

Round towers themselves are a perennial source of interest to antiquaries although there has been no serious architectural survey in depth. Thus, various estimates are available of the number of these churches, so short of checking out each church in East Anglia, I took the weighted mean from nine authors and found that there are thought to be about 42 such churches in Suffolk, whereas in Norfolk estimates vary widely, but there is a modal cluster around 134. There is an unspecified number in the neighbouring counties, particularly Cambridgeshire, and so we would probably be right to think in terms of about 200 round-towered churches in the area. Why then were the churches built to this plan?

It might be more sensible to ask why other churches were built with square towers, since non-ecclesiastical towers have generally been round. The followup from this line of lateral thinking is that the round church-towers were originally meant for some mundane purpose and only later had a church built on. In favour of this theory is the observation of flue and chimneys in several Norfolk round towers – were they kilns? – the fact that the towers generally predate the body of their churches, and their similarity to castle turrets (cf. city walls of Great Yarmouth, having exactly the same design of towers), which leads to the popular local speculation that the church-towers were originally watch-towers or defence-towers. This last theory is shaky, for although towers like that at Theberton in Suffolk, at the edge of a plateau 15 metres high overlooking the floodplain and marshes to the west, would be well-suited as lookouts, the tower, say, at Rickinghall (Inferior) in the same county, sitting at the bottom of a valley by a tiny unnavigable stream, is not very well situated at all. The towers’ battlements, where there are such, are always, as far as I know, several centuries later than the shaft of the tower, and the “arrowslits” that serve for windows are surely just a practical answer to the lack of glass in those times. (I am indebted to W.J. Goode’s paper in the report for 1974 of the Lowestoft Archaeological and Local History Society for a critique of the “defensive” theory.)

A favourite theory, begun it seems by Samuel Woodward, the Norwich antiquarian, in 1829, is that square towers could not be built in.areas lacking hard stone for the corner quoins needed. Rickinghall Inferior is again a counter example. The tower was built at around 950, the main (square) part of the church proper by 1010. The square-towered church at Rickinghall Superior was built at the same time. And round-towered churches extend a good sixty miles inland, into the hardstone areas. Possibly they spread inland from the coastal areas, otherwise the theory needs further substantiation by dates and locations of quarries compared with dates of the towers. {2}

But what concerns us here is more particular: those round towers that have an eight-sided upper storey. The octagons are all (to my knowledge) later than the main tower, and often were built while other embellishments were taking place as well. Not only octagons were added: the church at Haddiscoe has no fewer than five round stages, separated by girdles of stone, of which the top one is chequered in stone of different colours. Sometimes a double stage was added, as at Thorpe Abbots, where the upper stage of the octagon has windows on alternate (axial) sides. Rollesby has an octagonal tower down to the nave roof, with only one cincture of stone at the usual upper level. At Old Buckenham and at Buckenham Ferry the whole tower is octagonal, the first in Decorated style, the second is of two dates both indeterminate. (I refer to Charles Cox’s study of Norfolk churches.) Heckingham, another total octagon, is Early English, as is Toft Monks.

The round shafts of these towers are made of flint chips and pebbles, the octagons of various materials, particularly a kind of stone bricks, which are used at least for the edges, of course, whether or not flints are used to fill in the main part of the wall. Theberton church has a round cincture of stone at the base of the octagon, others have an octagonal cincture of straight stone (easier to work). A third stage of embellishment can be seen when elaborate battlements are added, e.g. the fifteenth century battlements on the fourteenth-century octagon of Raveningham’s round Norman tower! There are a few very late octagons. Bexwell’s octagon dates from 1730, Roydon’s also is “modern” to Cox, Clippesby’s was built in 1875, and the heptagon at Bylaugh dates from the 18th century. I do not know whether the whole church at Bylaugh is built ‘ad triangulum’ or not.

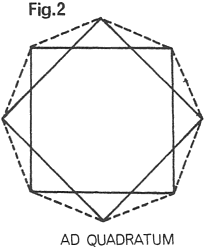

The octagon is a standard figure of church architecture, from the towers at Wymondham and the lantern at Ely to the familiar East Anglian octagonal font. It is formed by joining up the vertices of a reduplicated square, (Fig. 2). Buildings planned according to the layout of a square are said to be planned ‘ad quadratum’, which is the plan of most English churches. There are a few which are ‘ad triangulum’, such as King’s College Chapel, probably the most famous example. The mystic significance of geometric figures has always been with us, but it received an extra boost in England by the knowledge brought back from Arabic culture by the Knights Templar. The “pre-Socratic” teachings of the Pythagoreans had been absorbed by Arabic mathematicians and theologians, transmitted into their culture, and passed on to the West partly by monastic translations of Arabic works, partly by “heretical” Templar doctrines. The Arabic Qabalah teaches that the circle is the symbol of perfection, of deity and cosmos. The square on the other hand is all that is most fixed, the symbol of inertia and the Earth. In between them lies the octagon, result of the attempt to square the circle. It is halfway between subtle and gross, a mediator between divine and mundane. There may well, then, be some significance in the existence of these octagons, at the top of their towers between heaven and earth. There will then also be some meaning to the existence of the five towers that are octagonal to the base. And why are they placed on top of round towers not (except in the cases of Scoulton, Methwold, Upwell and Thuxton) on square ones?

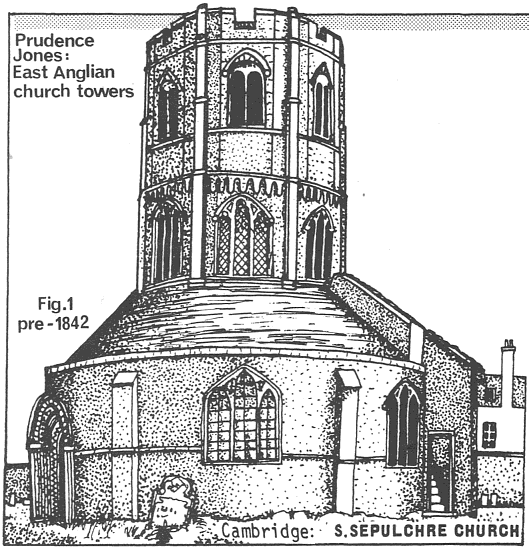

One tempting theory is to link these towers directly with the Templars. There was at least one commandery, that at Carbrooke, in Norfolk, and the knights could have set out from there to raise sacred buildings in the surrounding countryside. The octagonal-towered church at Rickinghall Inferior contains an effigy of Isabella, the “She-Wolf of France” #8211; “before”, says the guide-book, “she became the She-Wolf and persecutor of the Knights Templar.” {3} It is easy to hope that the octagons on the round towers echo the octagonal infrastructure of the Templars’ round churches, themselves built on the lines of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. However this won’t do, for examination of the chart of dates will show that of 49 dated octagons, three are 13th century, 20 fourteenth-century, 24 fifteenth century and four recent. The Knights Templar were dissolved in 1312, rather early in the thirteenth century, perhaps, for twenty out of 49 churches to have been built by that date. And of course, after the suppression, no-one would show any sympathy, in architecture or otherwise, with the Templars. Either, then, the octagons were so arcane as to be safe to build after the suppression of the Templars, or else they had nothing to do with that Order at all.

But there is another point to be kept in mind. It was in the fifteenth century that an octagonal upper lantern was built onto the Templars’ Round Church in Cambridge. (Fig. 1.) Is it part of the same wave of building that embellished our round towers, and if so what was the origin of that wave?

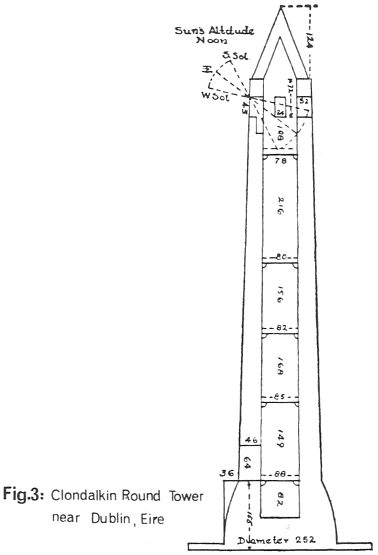

I have asked many more questions than I have answered. Still to be asked are these questions: whether any large-scale landscape geometry is involved in the siting of these churches; whether the octagon towers themselves have any solar or astral line-of-sight properties as in the Clondalkin Round Tower illustrated; (Fig. 3.) and of course whether the late – post-Renaissance – octagons are just copies or are built from the same principle as their originals,

My own research continues. Other people’s results and ideas would be welcome, either as articles for the Journal of as messages passed on in the Newsletter. And if the whole thing turns out to be a red herring then at least we shall all know not to waste our time on the topic any more.

| Church | main fabric | tower | octagon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acle | 14C | Norm. | Perp. |

| Burlingham St. Peter | Norm. | 15C | |

| Buckenham Ferry | |||

| Hassingham | late 14C | ||

| Witton | |||

| Breccles | Norm. | 15C | |

| Watton | Norm. | 14C | |

| Bedingham | Norm | 15C | |

| Heckingham | E.E. | E.E. | |

| Poringland | Norm. | Dec. | |

| Raveningham | Norm. | 14C | |

| Surlingham | Norm. | 14C | |

| Topcroft | Norm. | 15C | |

| Toft Monks | E.E. | E.E. | |

| Woodton | Norm. | ||

| {4} | |||

| Croxton | Norm. | 14C | |

| Feltwell St. Nicholas | Norm. | 15C | |

| S. Pickenham | Norm. | 15C | |

| Stanford | late Dec. | Norm. | 15C |

| Fritton | Norm. | 15C | |

| Beachamwell St. Mary | 14C | Sax. | Dec. |

| Bexwell | Norm. | 1730 | |

| W. Dereham St. Andrew | 15C | Norm. | 15C |

| Wramplingham | Norm. | 14C | |

| Intwood | 14C | Norm. | Dec. |

| Swainsthorpe | Norm. | 14C | |

| St. Benedict, Norwich | Norm. | 14C | |

| St. Etheldred „ | Norm. | 15C | |

| St. Paul „ | Norm. | 15C | |

| Needham | Norm. | 15C | |

| Roydon | Norm. | modern | |

| Rushall | Norm. | 15C | |

| Shimpling | Norm. | 15C | |

| Thorpe Abbots | Norm. | 14C | |

| Old Buckenham | Dec. | Dec. | |

| Quidenham | Norm. | Richard II | |

| Rockland St. Peter | Perp. | Norm. | 15C |

| Catton | Norm. | (later) | |

| Taverham | Sax./Norm. | 15C | |

| Kettlestone | 15C | 14C | |

| Burgh St. Mary | Perp. | Norm. | Perp. |

| Clippesby | Norm. | Norm. | 1875 |

| Mautby | Dec. | Norm. | Perp. |

| Repps | Sax./Norm. | 1275 | |

| Rollesby | 14C | Norm. | Dec. |

| W. Somerton | 1310 | Norm. | Dec. |

| Sedgeford | 14C | Norm. | Dec. |

| Brampton | Dec. & Perp. | Norm. | Perp. |

| Gresham | Dec. | Norm. | 19C |

| Matlask | Norm. | later | |

| Billingford | Dec. & Perp. | ||

| Morton-on-Hill | 13C 14C 15C | Norm. | 14C |

| St. Ryburgh | 15C | Sax. & Norm | 15C |

| Horsey | Norm. | 15C | |

| Potter Heigham | 14C | Norm. | 14C |

| Theberton (Suff.) | Norm., 15C | Norm. | 1300 |

Since this article was written, several studies on the subject have been published by the Round Tower Churches Society.