Ancient Mysteries no. 16, July 1980 (continuation of Journal of Geomancy)

{22}

It may be of interest to readers to have an account of a recent Russian theory about the layout of Stonehenge. Most readers are probably familiar with Mike Saunders’s booklet Stonehenge Planetarium (1979) in which he links the various rings of stones and holes with the orbits of the planets about the sun.

The Russian theory, proposed by Vladimir Avinsky and Valentin Tereshin, is also of a planetary nature, but links the rings of stones and holes with the sizes of the planets themselves, rather than with their orbital radii.

Details of the Russian theory are hard to find. A brief account appeared in the Daily Mail for September 20th 1979, hut no full account seems to have been forthcoming in English. The present article, which I hope will fill the gap, is based on a paper called New Discovery of Stonehenge, printed in Volzki Comsomolets (N21, 1976), translated by V. Sinin. The English of this translation, which was kindly sent to me by Mike Saunders, is not as good as one would like, and some of the ideas in it are not very clearly defined to boot. In fact, as regards two parts of the proposed planetary basis for Stonehenge, I am making something of a guess based on a none-too-precise diagram accompanying Sinin’s translation.

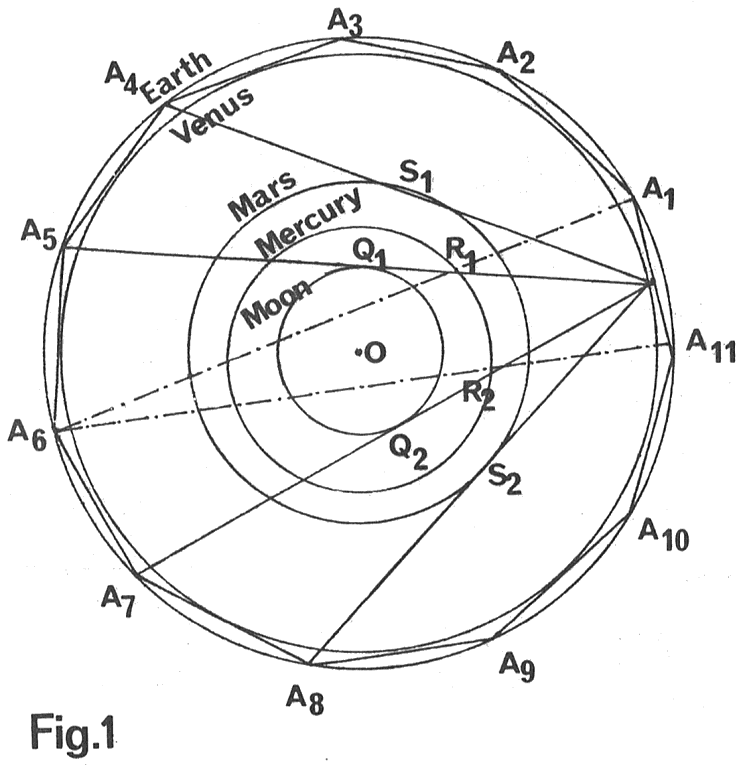

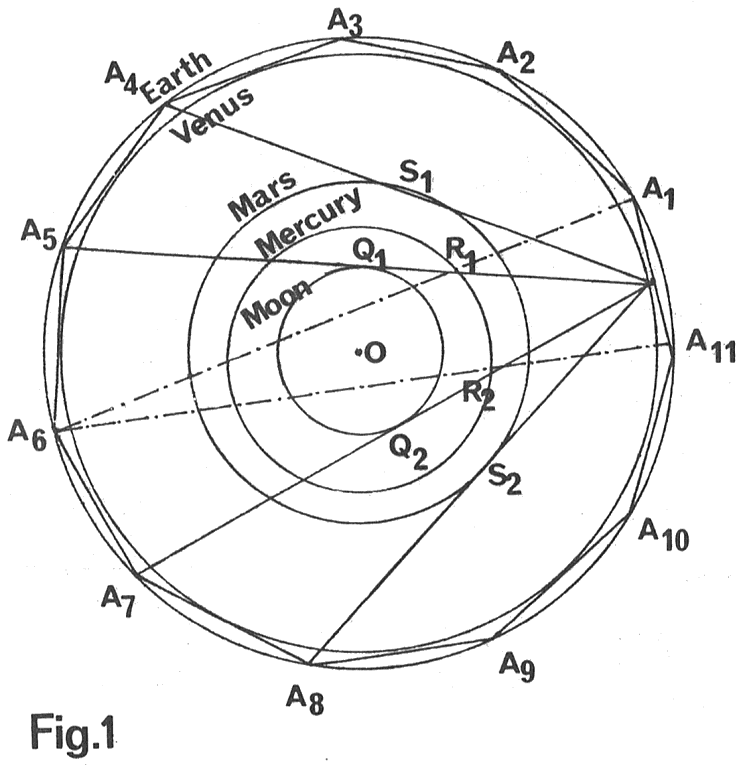

Basically Avinsky and Tereshin contend that Stonehenge was constructed from a regular 11-sided polygon, 11-gon for short, A1, A2, …, A11 of Fig. 1. O is the centre of this polygon.

If the circumscribed circle of this 11-gon be taken to represent the earth, then its inscribed circle will represent Venus. That {23} is, the outer two circles of Fig 1 represent the earth and Venus. For simplicity, in what follows, the radius of the earth circle as taken as 1 unit. “Avinsky and Tereshin give” will mean that a radius being quoted is that calculated from the geometry of Fig 1. The phrase “in practice this should be” will refer to the actual planetary radii on a scale of earth = 1 radius.

If the radius of the outer, earth, circle in Fig 1 is 1 unit, then Avinsky and Tereshin give 0.9595 units for the radius of the Venus circle. In practice this should be 0.9489 units.

Now, in Fig 1, join P, the midpoint of A1A11, to A4. Then the Mars circle has centre O and is tangent to PA4. For the radius of this circle, A & T give 0.5293 whereas in practice it should be 0.5320.

Now join P to A5 and construct a circle centre O, tangent to PA5. This circle represents the Moon, A & T giving its radius as 0.2759 units whereas in practice it should be 0.2725 units.

The circle representing Mercury appears to have centre O and to pass through the point of intersection of PA5 and A1A6. (This is one of the places where I’m guessing what the theory is from Sinin’s diagram). If this is the case then A & T give the radius of this circle as 0.3767 units, whereas in practice it should be 0.3826 units.

Now, it is upon this remarkable geometric link between the sizes of the inner planets that A & T claim the groundplan of Stonehenge was based. The earth and Venus circles define the surrounding bank. The Y holes are on the Mars circle, the Z holes on the Mercury circle, and the Sarsen Circle defines the Moon circle.

The central horseshoes and the bluestone circle seem to have no place in A & T’s construction, or if they do, it isn’t clear from Sinin’s diagram. The Aubrey Holes seem to have a rather obscure derivation based on the so-called pentagram.

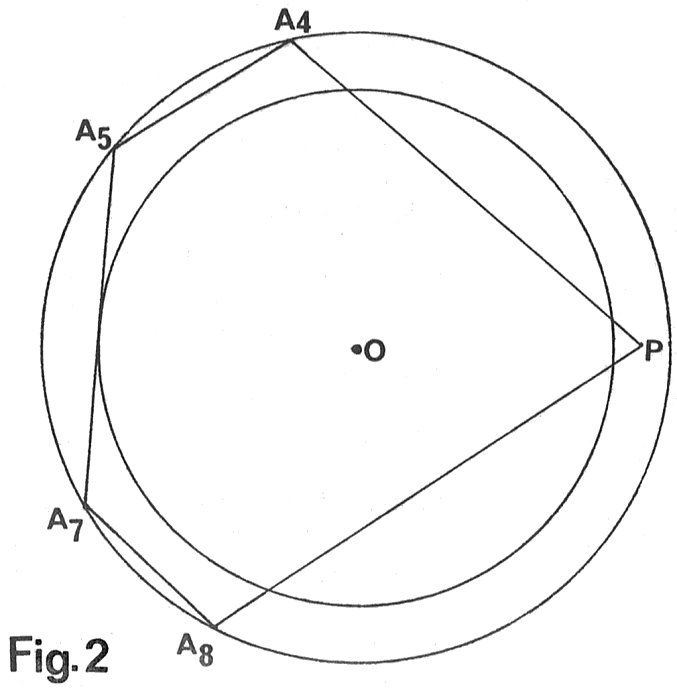

The English newspapers suggested that A & T’s construction used a pentagram, which to English readers rather suggests a regular pentagon and 5 {24} pointed star (compare Inigo Jones’s 6 pointed star). However the pentagram here appears to be PA4A5A7A8, and the diagram accompanying Sinin’s translation suggests that the Aubrey Holes are defined by a circle centre O and tangent to A5A7 (see Fig 2).

I make no attempt here to discuss A & T’s claim that a regular 11-gon can be marked out by observing the extreme azimuths of the rising moon as seen from Stonehenge, or that this same bag of geometrical tricks can be used to square the circle. Readers who want to go into those matters must hunt out the original for themselves.

Nor do I intend to list one thousand and one reasons why I think Messrs. Avinsky and Tereshin are well and truly up the creek.

I am writing this largely because details of this Russian extravaganza are not readily available in English, but also because, if nothing else, A & T’s “new discovery” shows how easy it is to fit intriguing theories to a monument like Stonehenge.

Now, there’s a fellow called Thom … professor of Engineering or something … who’s got the real dope on the layout of Stonehenge … well, he’s a professor, so he must know, mustn’t he?

{25}