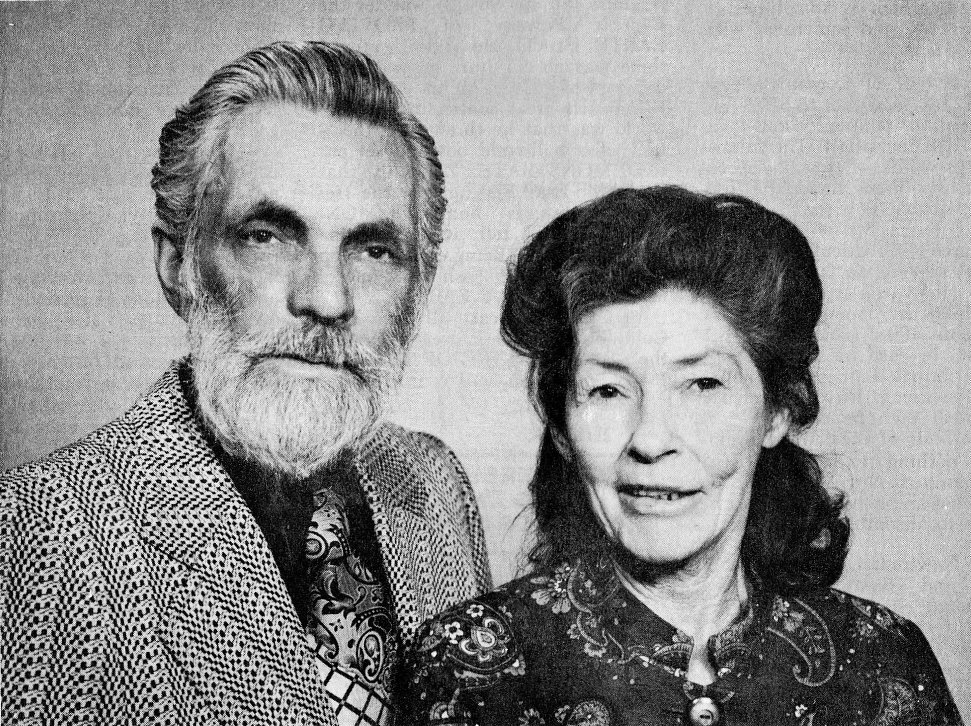

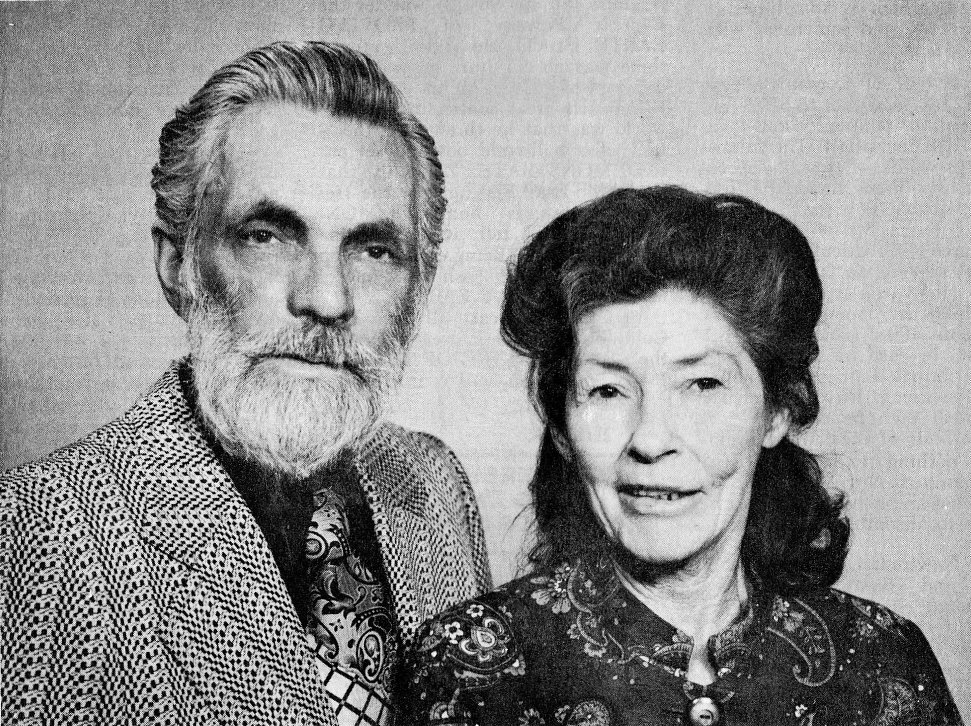

Charles and Marjory Johnson (from The Flat Earth News, September 1979).

When the year 2000 approached, the Flat Earth Society was headquartered on a California hillside among Joshua trees, creosote bushes, and tumbleweeds. The Mojave Desert lies below, looking flat as a pool table. About 20 miles to the west is the desert city of Lancaster; you can see right over it. Beyond Lancaster, 20 more miles as the cue ball rolls, the Tehachapi Mountains rise up from the desert floor. North of Lancaster is the Rockwell International plant where the Space Shuttle was built. Further north, out of sight behind a nearby hill, lies Edwards Air Force Base, where the Shuttle was tested. Los Angeles is not far to the south.

The headquarters building, a modest cabin on a 5-acre plot, was home to Charles and Marjory Johnson since 1972. At election time, it doubled as the polling place for the eastern half of the precinct. The power lines ended at the bottom of the hill, but the Johnsons had a diesel generating unit that supplied power for home and headquarters during the cool evening hours. Heading the Flat Earth Society was a full-time job for Charles Johnson, and having his office at home made it easy to catch up on his work after the desert sun set.

A small, nonprofit organization can take on the image of its leader, and Johnson’s Flat Earth Society was no exception. Johnson was a remarkably well-read, strongly opinionated, self-taught individualist. Part of his time was devoted to editing what surely was the nation’s most frankly worded quarterly, The Flat Earth News, for distribution to members. Part of his time was devoted to answering inquiries about the society.

Charles Johnson was a bearded, distinguished-looking man who drank coffee seemingly by the gallon. He chain-smoked, hand-rolling cigarettes so skillfully that they would seem factory made. His soft voice still had a touch of Texas. Unlike the stereotypical prophet, he had a wry sense of humor and a booming laugh. Fond of plays on words, he stated “The foundation of science is the spinning grease-ball. They claim the ball comes from Greece, so I just say ‘grease-ball.’ It’s a ball-bearing universe.”

Charles Kenneth Johnson was born on his father’s ranch near San Angelo, Texas, in 1924. Soon afterward, his family moved into town. Johnson’s father was born “dirt poor” but, according to Charles, with hard work and a bit of borrowed money he became “quite a cattleman in Texas” to the extent that (also according to Charles) Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove could have been a biography of the elder Johnson. His father always told Charles to live in such a way that he wouldn’t be ashamed to look any man in the eye. The elder Johnson died in the early 1940s when Charles was a young man of about 20 years. His mother, quite a bit younger than his father, died in 1996 at the age of 93.

Johnson could vividly recall the day, sometime in the early 1930s in San Angelo, Texas, when his grade school teacher first presented the globe to his class. Johnson was skeptical. Why, he asked, didn’t things fall off? The teacher told him that if you swing a bucket of water over your head fast enough, the water won’t spill out. When he got home from school, he took a bucket out to the well, pumped some water into it, and swung it around. The water didn’t come out but, like John G. Abizaid (see Chapter 8), he could see that the demonstration had nothing whatever to do with the shape of the earth. Johnson rejected the globe on the spot, and never found reason to change. “You can train the two-footed Animals in the schools,” he once said. “You can tell them that the earth is a bowl of jelly, and they’d accept that just as well as anything else. Somebody would come along and say, ‘It must be jelly, ’cause jam don’t shake like this.’ It would be a good dogma, and the average person would accept it just as well.”

Johnson formally parted company with the spherical school system as a teenager, but he continued his education on his own, reading voraciously. He worked in various places in Texas, then in Colorado, and finally ended up in California. In 1959, he walked into a San Francisco record store to buy a copy of Acker Bilk’s haunting hit, “Stranger on the Shore.” Inside he found Australian-born Marjory Waugh buying the same record. He soon discovered that they had more in common than their taste in music. They were both ethical vegetarians and ardent antivivisectionists, but their overriding interest was geodesy. Marjory also was a life-long flat-earther. When fate plays cupid, who can resist? Love and marriage ensued.

Charles and Marjory Johnson (from The Flat Earth News, September 1979).

Sometime in the late 1960s, the Johnsons heard about Samuel Shenton, a Dover, England, sign painter who was trying to revive the British flat-earth movement. Charles Johnson immediately wrote to Samuel Shenton and applied for membership. He was accepted and a satisfying correspondence ensued.

Shenton and William Mills founded the International Flat Earth Society on December 20, 1956. Shenton was the guiding force. Mills died soon afterward, on May 25, 1960. Mills provided one of the links with the past, for he was related by marriage to Frederick Henry Cook, whose Terrestrial Plane, or the True Figure of the Earth was self-published in 1908. Indeed, one of Mills’ sons died suddenly on December 18, 1957, and left £500 to be used to finance publication of his uncle’s unpublished flat-earth manuscript. It is titled Our Earth Flat, Not Spherical and is 382 pages in length. Cook apparently completed it in about 1947 as he wrote, “Nearly forty years have passed since the Author wrote his first book (on the true figure of the earth) …”

Shenton actively promoted the International Flat Earth Society. He gave dozens of lectures on the flat earth in which he would use his skill as a sign painter to prepare flip charts illustrating his view of the earth and universe. Shenton’s view differed slightly from previous flat-earthers. He believed in a literal seven heavens, the first immediately above the dome covering the known world, and the rest stacked above it. He had a complex theory of how the alleged space capsules moved above (not around) the earth, and he explained this in detail in his lectures.

Shenton received enquiries from all over the world. Roughly half of them seem to have come from high school students, many of them in America. A typical letter began, “Dear Mr. Shenton, I am 14 years old …” Most of the letters from adults were obviously from curious skeptics, many of whom requested free information, pamphlets, and so forth. It’s not clear how many of these requests Shenton honored. Some wrote to argue, assuming (generally wrongly) that they knew more about the evidence for the shape of the earth than Shenton did. Almost invariably these writers offered arguments flat-earthers considered decisively answered a century previously. Some were ambiguously worded as if intended to be misunderstood, and one doubts that Shenton was either conned or favorably impressed by these.

Another common class of letter was an invitation to speak. Shenton frequently honored these requests, and the correspondence shows that he usually requested a modest fee (perhaps £5) plus travelling expenses. Many of the requests came from secondary schools, social clubs, or school-affiliated clubs (the Young Liberals or Young Conservatives, for instance). A few came from college and university departments.

The rarest letters were undoubtedly most valuable. A goodly minority wrote to Shenton to express their whole-hearted agreement with his flat-earth views. Some provided nuggets of history or links with the past. It was presumably from these that Shenton selected his members.

Shenton did his best, but he was never able to attract many members. With the advent of the space program, however, he attracted a lot of reporters eager to hear him explain the satellites allegedly orbiting the earth, photos of a globe supposedly taken from deep space, etc. As is their custom, the British news media had a lot of fun with Shenton. A few articles about him were printed in America, and it was one of these that alerted the Johnsons.

Before he died in 1971, it was Shenton’s last wish that the mantle of leadership be passed on. After Shenton’s death, there was a brief false start for the International Flat Earth Society as Shenton’s widow, Lillian, tried to keep it going. Shenton, himself, had picked Ellis Hillman to become president, but it wasn’t meant to be. With Hillman’s unwillingness to step up and Shenton’s experience with the British news media, Johnson believed that America would be more hospitable than England as international flat-earth headquarters and so the transfer to America was made. The mantle of leadership along with a small but precious library of flat-earth books was passed on to Johnson in 1972. Johnson’s Flat Earth Society was a spiritual inheritor of the Universal Zetetic Society, which had flourished in England.

Letters poured into his Lancaster, California, headquarters from all over the earth. His job was to get the Plane Truth before the public, and he conscientiously answered all requests for information. He also reached the public through interviews in magazines and newspapers, frequent appearances on radio call-in talk shows, and occasional TV interviews and public lectures.

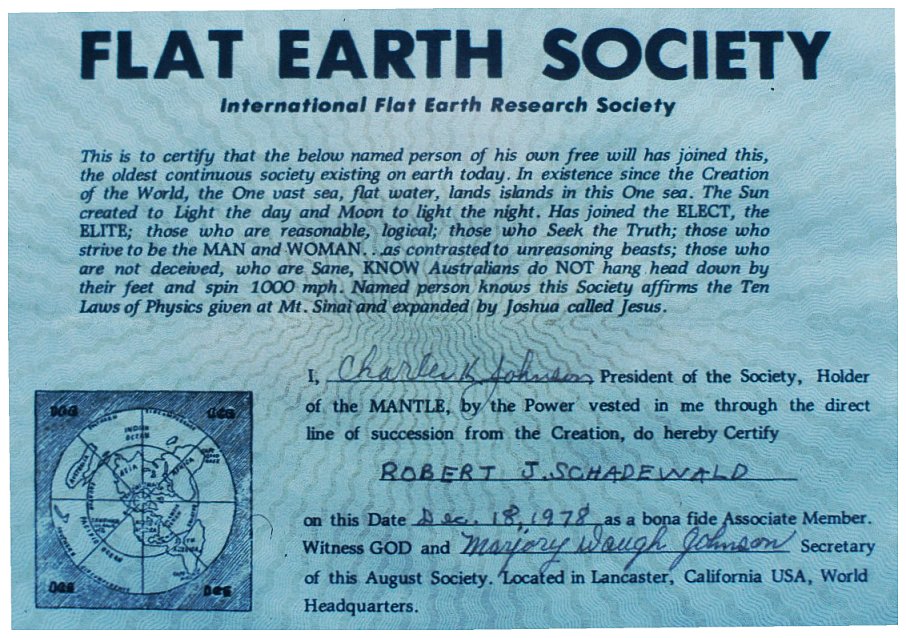

Under Johnson’s full-time presidency, the society’s paid-up membership grew from a few to a few hundred paid-up members. Membership was open to anyone regarded as sincerely seeking the truth. Ever since Johnson felt compelled to evict a skeptical writer for spherical tendencies, he required prospective members to sign an agreement stating that they would never defame the society. Those accepted received a membership card, a certificate, and a subscription to The Flat Earth News, a marvelously outspoken quarterly tabloid with a style reminiscent of 19th century southern journalism.

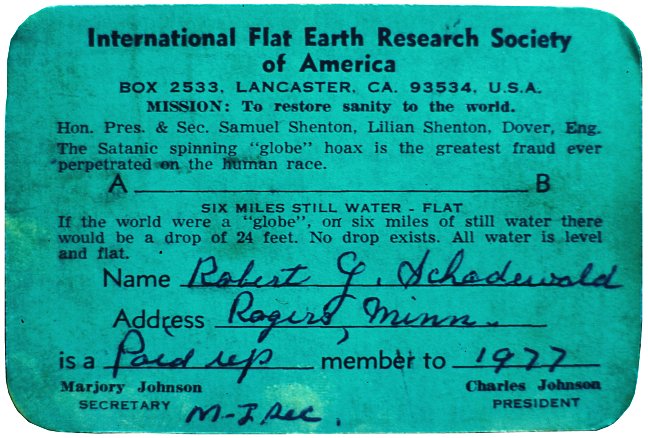

The author’s membership card for the Flat Earth Society. Samuel and Lillian Shenton are named as Honorary President and Secretary, though Samuel, at least, was no longer alive.

While Johnson didn’t contribute much to flat-earth theory—he considered the zetetic system to be well established and essentially complete—he did speculate a bit on why the globular theory prevails. Johnson believed that the governments of the world are all run by flat-earthers, but they keep up the spherical pretense to keep the masses under control. The space program is partly for the latter purpose and partly as a WPA [note 9.1] project to provide jobs for otherwise unemployable Kennedy Democrats. One of these days, however, there will be a public declaration that the earth is flat, and a new era will follow. It almost happened at the end of World War II.

“Uncle Joe [Stalin], Churchill, and Roosevelt laid the master plan to bring in the New Age under the United Nations,” Johnson declared in a 1980 interview. “The world ruling power was to be right here in this country. After the war, the world would be declared flat and Roosevelt would be elected first president of the world. When the UN Charter was drafted in San Francisco, they took the flat-earth map as their symbol.”

Seal of the United Nations.

Indeed, the United Nations seal, an azimuthal equidistant polar projection, is precisely the flat-earth map as drawn by Rowbotham and identical with the world map that hung on Johnson’s office wall. However, Franklin Roosevelt died coincident with the UN’s birth and Johnson believed that threw a monkey wrench into the plans. But, according to Johnson, the setback was only temporary, and the declaration may come sooner than most people think. When it does—when the government publicly admits that sunrise and sunset are mere optical illusions—the declaration will fulfill the prophecy of Isaiah 60:20 that “the sun shall no more go down.” Johnson believed it will usher in an era of peace, prosperity and morality under a benevolent world government. Surely that’s something to think about.

Johnson’s Flat Earth Society’s official letterhead boldly proclaims its mission: “To restore sanity to the world.”

“In order to be sane,” Johnson once told me, “you have to understand the reasonableness of your own common sense. You have to start out with self-evident things, instead of this wild, weird stuff” (read: space program).

Most people don’t know the Flat Earth Society exists. Those who do are typically confused about who runs it. Some think it’s an English society and that Johnson’s group was a U.S. branch. Others confuse it with a Canadian outfit whose seriousness about the flat-earth business is open to serious question. Many seem astonished to learn that it still exists at all.

Membership certificate for the Flat Earth Society, somewhat later than the card shown above.

As seen in earlier chapters, old-time flat-earthers were often Scripture-spouting zealots. Indeed, Wilbur Glenn Voliva, America’s foremost flat-earther in the 1920s, was head of the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church of Zion, Illinois. While Johnson acknowledges the work of his religiously-oriented predecessors like Voliva and England’s Samuel Shenton, he had a different image of the Flat Earth Society.

“We don’t quote Scriptures,” he said, “though we mention that the Bible is a flat-earth book. We concentrate on the evidence.”

Most of those currently seeking scientific truth in the Bible ignore its flat-earth implications. Geocentricity is another matter, and several prominent scientific creationists repudiate Copernicus on scriptural grounds, opting for the fixed-earth system of Tycho Brahe. Johnson scorns such halfway measures.

“I like ‘Co-pernicious’ much better,” he said, deliberately mispronouncing the name of that Polish luminary. “Imagine this ball that they claim is just hanging there with ships sailing over it! At least ‘Co-pernicious’ had the sense to set the whole thing whirling to try to give some explanation for why you can hang on. Certainly, if I had to choose between the two, I’d choose Cope.”

Johnson contended, “Nobody knows anything about the true shape of the world. The known, inhabited world is flat. Just as a guess, I’d say that the dome of heaven is about 4,000 miles away, and the stars are about as far as San Francisco is from Boston.”

Although Johnson did not use the Bible as his sole evidence for the flat earth, his beliefs were nevertheless firmly confirmed by the Bible. Many verses of the Old Testament imply that the earth is flat, but there’s more than that. According to the New Testament, Jesus ascended up into heaven.

“The whole point of the Copernican theory is to get rid of Jesus by saying there is no up and no down,” declared Johnson. “The spinning ball thing just makes the whole Bible a big joke.”

Not the Bible, but Johnson’s common sense allowed him to see through the globe myth while he was still in grade school. In 1981, Johnson went back to the John H. Reagan School that he attended in San Angelo, Texas. “It still looks like it always did. I know what room they showed me the globe in” he said. There it was, almost 40 years after Johnson first discounted it. Johnson printed a picture of himself pointing to the globe in The Flat Earth News. “The same school building, the same room, and the same globe responsible for the present Flat Earth Research Society.” Johnson said, “It started with me right here when I was seven or eight years old.” He contends that it is not just Bible believers, but sensible people all over the world who realize that the earth is really flat.

In the early 1970s, Charles Johnson heard about a group in San Diego dedicated to defending the Bible. The new organization, the Institute for Creation Research, insists that the Bible is literally true. Johnson contacted his San Diego counterpart, fellow Texas native and founder of the Institute for Creation Research, Henry Madison Morris.

The two titans of modern Bible-science, so alike and yet so different, did not hit it off. Johnson was a simple son of the Texas soil, unpolished, unpretentious, and largely self-educated. Morris was an unrepentant elitist who would flaunt his Ph.D. in hydraulic engineering like an insecure big spender flashing a roll of bills. [note 9.2] Morris headed a big-budget nonprofit organization, from which he drew a substantial salary. Johnson and the Flat Earth Society languished in semiobscurity, operating on an annual budget which was typically supplemented from Johnson’s personal funds.

Both considered themselves instruments of the Almighty. Both were self-educated students of the Bible, although they came to markedly different conclusions about what it teaches. Morris would get hysterical when anyone suggested that the Bible is a flat-earth book. Johnson felt that the Bible was partially corrupted, and contains many things that don’t belong there, such as the stories of divinely ordered massacres. Morris ardently defended the Biblical stories of genocide. He would argue, for instance, that if the Canaanite women had not been massacred, they would have led Israelite men into idolatry. Likewise, the massacred infants were saved from earning damnation through idolatry.

Perhaps it was Johnson’s experience with Morris that led him to purge the Bible-thumpers from the Flat Earth Society. Whatever the reason, Johnson did with the Flat Earth Society what Morris only claimed to have done with creationism: he put it on a secular, nonsectarian footing.

It was not science that led Johnson to his conviction that the earth is flat, but facts and evidence that he gathered through his own experience. Johnson believed that science is a religion of its own with its own dogmas and absurdities. “We concentrate on the evidence,” Johnson said.

When asked his opinion of a bill which was proposed to be introduced in various state legislatures called A Balanced Treatment of Flat-Earth Science and Spherical-Earth Science Act Johnson replied, “But we don’t believe in science. I mean, this is what you call the kiss of death when you say ‘flat-Earth science’. That’s what happens to the creationists, for instance.” He continued, “It’s like Baptists going into a Catholic church and wanting to teach Baptist doctrine.” What, then, was the basis of the Flat Earth Society under Johnson? “Our stuff is not science, because science is the blind faith in Asiatic religion. In order to be a scientist you have to give up all desire for truth and facts.” He continued, “It’s not flat-Earth science, but flat-Earth facts that we have.”

Would he have supported this type of bill, though, in the interest of fair-mindedness? “No, I wouldn’t support that at all. This is a confrontation. We don’t want to get equal time. The two can’t exist together. The flat-Earth and the ball are not the same. If the flat-Earth is taught, the ball must be exposed as a total hoax and thrown out all together. It’s all or nothing.”

Would he have supported Morris’s stance that creationism should be taught as an alternative theory of the origin of humankind? “If it weren’t for Morris and his gang, they could teach creation in the schools: Some people think the universe and all forms of life were created, and that’s it. That’s all that needs to be said. But Morris wants to argue over how many hours were in a creation day, he wants all this science, and that has ruined everything. Morris wants to get in one version of religion and quote scriptures all the time.”

As secretary of the Flat Earth Society, Marjory Johnson assisted in running it, and wrote a regular column in the News. She also helped her husband perform experiments to determine the earth’s shape. If it is a sphere, the surface of a large body of water must be curved. The Johnsons checked the surfaces of Lake Tahoe and the Salton Sea (a shallow salt lake in southern California near the Mexican border) without detecting any curvature.

Charles Johnson claims that most of the people who shaped our modern world were flat-earthers, and some of them didn’t have it easy, either.

“Moses was a flat-earther,” he reveals. “The Flat Earth Society was founded in 1492 B.C. when Moses led the children of Israel out of Egypt and gave them the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai.”

Conventional biblical chronology, as established by Archbishop Ussher, dates the Ten Commandments to 1491 B.C., but it may be imprecise. Perhaps Johnson prefers 1492 for the symmetry. It was, after all, in 1492 A.D. that another famous flat-earther made history.

Have you heard the story about Columbus’s problems with his crew? As some tell it, the crew nearly mutinied because they regarded the earth as flat, and feared they might sail off its edge.

“It was exactly the reverse,” explained Johnson. “There was a dispute out there on the ship, but it was because Columbus was a flat-earther. The others believed the earth to be a ball, and they just knew that they were falling over the edge and couldn’t get back. Columbus had to put them in irons and beat them until he convinced them they weren’t going over any curve, and they could return. He finally calmed them down.”

Johnson believes that the ball business—though it goes back to the Greek philosophers—really got rolling after the Protestant Reformation.

“It’s the Church of England that’s taught that the world is a ball,” he argues. “George Washington, on the other hand, was a flat-earther. He broke with England to get away from those superstitions.”

If Johnson is right, the American Revolution failed. No prominent American politician is known to have publicly endorsed the flat-earth theory in the past two centuries.

What did happen, according to conventional historians, was that Russia and the U.S. began space programs. After the Russians sent up Sputnik in 1957, the space race was on in earnest. The high point came in 1969, when the U.S. landed men on the moon.

That, according to Johnson, was nonsense, because the moon landings were faked by Hollywood studios. He even named the man who wrote the scripts: the science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke. But he acknowledged that the moon landings were at least partly successful.

“Until then,” he said, “almost no one seriously considered the world a ball. The landing converted a few of them, but many are coming back now and getting off of it.”

Perhaps the Space Shuttle was intended to bolster the beliefs of these backsliders. Whatever its purpose, Johnson was once convinced that it was never intended to actually fly. Because it was built and tested almost in his back yard, he knew many of the people who worked on it. What they told him about some aspects of its construction only reinforced his convictions.

“They moved it across the field,” he sneered, “and it almost fell apart. All those little side pieces are stuck on with epoxy, and half fell off!”

The Shuttle had other problems besides heat resistant tiles that wouldn’t stick. For instance, when the testers tried to mount it on a 747 for its first piggy-back flight, it wouldn’t fit.

“Can you imagine that?” chortled Johnson. “Millions of dollars they spent, and it wouldn’t fit! They had to call in a handyman from Rosamond to drill some new holes to make the thing fit. Then they took it up in the air—and some more of it fell to pieces.”

Flat Earth Society members are still working actively to bring the Shuttle charade to an end. They hope to force the government to let the public in on what the power elite has known all along: the plane truth.

“When the United States declares the earth is flat,” Johnson once told me, “it will be the first nation in all recorded history to be known as a flat-earth nation.

“In the old days, people believed the earth was flat, because it’s logical, but they didn’t have a picture of the way it was, as we have today. Our concept of the world is new.

“Marjory and I are the avant garde. We’re way ahead of the pack.”

The Johnson home was a half-mile from the nearest neighbor. Friends would drop in now and then, but their primary companions were a half-dozen dogs, several cats, a flock of chickens, and a myriad of sparrows roosting in the Joshua tree outside the door. No electric-power line ran to the house, and water had to be hauled up the hill. The physical isolation was the ultimate in privacy—but another kind of isolation proved to be less desirable.

“We’re two witnesses against the whole world,” Johnson once observed. “We’ve chosen that path, but it isolates us from everyone. We’re not complaining; it has to be done. But it does kind of get to you sometimes.”

In 1995, the Johnsons’ home caught fire. Charles Johnson managed to rescue his wife, Marjory, by then an invalid, but most of the Flat Earth Society’s records and its fine collection of flat-earth literature were destroyed. Marjory Johnson died in May 1996; Charles Johnson in March 2001.