Translated from Germanien, 1934, pages 359–365

This translation was first published in Ancient Mysteries (Bar Hill, Cambridge), No.16, pages 26–31 and 34–36 (1980). A few corrections have been made in this Web version.

{26}

Troytowns

Everyone is familiar with the word labyrinth – although in most cases there is nothing more behind it than an uncomfortable memory of the schoolroom. Perhaps these dim recollections can still be concentrated into names such as “Theseus”, “Ariadne”, and “Minotaur”. But then in most cases we comeThese words accidentally omitted in 1980 version to a full stop. The distribution of labyrinths, mazes, shepherd’s races, Julian’s bowers, Troytowns, or whatever other names may be used, is as little known as the names themselves.

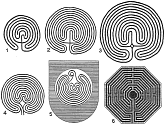

The best-known Troytown is probably that at Visby on the island of Gotland (Fig. 1,3), although on this island alone there are three others. It is laid out with tracks about a foot wide by means of stones as big as a man’s head, and according to tradition originated with a king’s daughter who was held prisoner by pirates under the Galgenberg (Gallows Hill). {27} Every day she placed one stone against another, until on her release the Troytown was complete. In North Slesvig, now ceded to Denmark, there exists near Visby, not far from Tondern, an earthwork which still bears the name Troiburg. A hill not far away is the Galgenberg, a name rare in those parts. Near Tondern itself old engravings show a place of the Rantzauschens, which is labelled “arx troiburgum” and is likewise situated on a Galgenberg. In the immediate neighbourhood of both these Troiburgs lies Gallehuus, which was in the news because of the golden horns found there. The Galgenberg at Meldorf in Ditmarschen is still a spiral today. And the Troytown of Steigra (Fig. 1,4 & 2–5), which will be further discussed below, is like the one in North Slesvig 5 km away from a Galgenberg, namely that at Burgscheidungen an der Unstrut, the town where, according to Widukind von Corvey, the Saxons erected their Irminsul pillar in 530 after defeating the Thuringians (Widukind, Res Gestae Sax. 1, 12). Another German Troytown existed at Graitschen near Camburg (Fig. 1,5), south of NaumburgWrongly ‘Hamburg’ in 1980 version (Fig. 2). Of this only the memory is left, preserved in the municipal coat of arms, which shows a Troytown. Again, the March of Brandenburg contained similar layouts, which were there known as “Jekkendanz” or “Wunderberg”. We find further examples of Troytowns from Iceland, where they are called “Völundarhus” (Wayland’s House) – from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, where the name Troytown is general – from Lapland, Finland and the shores and islands of the White Sea in Northern Russia. In Russia they are called Babylon, in Wales Caer-Droia, in England Troytown, walls of Troy, way to Heaven and road to Jerusalem. The last name is also used in France: chemins de Jerusalem. The name “labyrinth” derives from Greek mythology. The Cretan mazes inscribed on coins (Fig. 1,1) go back to the sanctuary of the bull-god Labyrinthios, whose symbol was the double axe (Greek labrys = double axe). Finally we also know of Egyptian mazes, of which the best-known was laid out by Lake Moeris about 2200 BC by King Amenemhat III as a temple for the whole kingdom. {28}

Ernst Krause cites, in connexion with the name Trojaburg or Troytown, the Old German “drajan”, the Gothic “thraian”, the Celtic “troian” and the Middle English “throwen”. In addition there are the Anglo-Saxon “thrawan”, the Dutch and Low German “draien”, the Danish “drehe” and the Swedish “dreja”, and the English “throe”. All these words mean “turn” and were applied to the twists and turns of the layout. Perhaps also the “Wunderberg” used in the March of Brandenburg is a corruption of an earlier “Wenderberg”, in which case the word “wenden” (to turn around) would be the origin. The Low German word “traaje” also belongs here. It denotes a deep wagon track, a rut, and nowadays may be replaced by the word “spoor” (same in English). As a verb it means to follow in the track of another. In pronunciation the double a changes, as in the Nordic languages, to an almost pure O, so that “traajen” is pronounced like “trojen”. From here the inference would extend to the tracks, dug in the earth or formed from stones, which one must follow on entering the Troytown. When one views the spirals cut in the turf, which look like the tracks formed by a wagon, the relationship cannot be denied.

Fig. 1

The period at which Troytowns were laid out has been the subject of lively debate. Dr Aspelin of Finland places

Troytowns in the Bronze Age, while the Russian researcher Yelisseyev considers them even older. Dr Nordström of

Stockholm was of the opinion that the designs were Christian ones, which were later transferred from churches into the

open air. He based this interpretation on the fact that in many old Italian and French churches such mazes still exist

as pavement mosaics. However, this must be erroneous, for Pliny reports in his Natural History (Book 26,

12, 19) on Troytowns in the open fields in Italy. Also the Greek and Egyptian labyrinths are

{29}

much older than the Christian church. And it seems strange that such things should have developed when they have no

foundation in the Christian religion. Actually the church took over Troytowns as it did many other things that for all

its efforts it could not suppress. This is shown for example by the remarkable drawings in the vault of the parish

church at Räntmaki in Finland

(Fig. 1,2).

If the labyrinths set into church floors can at a pinch be explained as “the

way to Jerusalem” etc., in the present case any such interpretation is impossible. For at Räntmaki the

Troytown is drawn on the roof of a vault, among other drawings still apparently pagan in style. Thus only one conclusion

is possible, that here a pre-Christian usage was taken over and given a new interpretation. Then during the Crusades the

name “way to Jerusalem” emerged. To the same period belongs an East Prussian tradition of the Order of

Teutonic Knights: in front of their castles the knights are said to have laid out mazes which they called

“Jerusalem” and which they won in battle from their servants every day, amid laughter and joking. They did

this in order to fulfil their vow that pledged them to unceasing struggle for the liberation of Jerusalem. Such is the

tradition. It harks back to much older things and customs. And it can hardly be supposed that the knights occupied

themselves with the Troytowns, nor constructed them. Much more probably, they built their castles and churches on the

sites of such designs, as indeed nearly all old churches and monasteries were located on old sacred sites of

pre-Christian times. The church can be given credit for one thing only: the more regular and perfect layout of the

mazes, which is certainly easier to recover among church mosaics than among the pre-Christian turf and stone mazes. The

artistry of many of the church labyrinths is shown by the one laid out in 1495 in the Quintinus Basilica at St. Quentin

(Fig. 1,6).

The design, built up

{30}

from 2200 pieces of stone, is based on 12 rings set around a central point. An artistic maze was then formed by moving

only 47 pieces (Möller-Fernau, Kosmos, 1932 p. 307).

Of course the shape of the Troytown was materially altered in the process. It is a feature of all ancient designs, whether in Greece or Scandinavia, that while the rings have a common centrepoint, they are not exact circles, so that the centrepoint is displaced somewhat downwards. It can safely be assumed that the various windings of the Troytown symbolize the yearly course of the sun. The fact that there are 12 separate rings speaks in favour of this; for there are only a few Troytowns with any other division. The horizontal arms of the clearly visible cross are then perhaps to be regarded as the horizon, so that the various complicated and rather compressed turnings beneath it represent the sun’s path under the earth (during the night). Perhaps this is also the origin of the bad reputation of crossroads, which must similarly have a Pagan basis because otherwise it is quite incomprehensible that the holy symbol of Christianity should be the haunt of the Devil. The crossing point is often occupied by a stone or, in turf-cut designs, marked out as a square baulk. On it sat the imprisoned maiden, who had to be freed, as we know from many customs still in use today. Something of this is preserved in the well-known children’s song “Mariechen sass auf einem Stein”. From many traditions and legends we know that bewitched people were changed to stone or banished into a rock. It is thus not too much to suppose that the sun as a maiden was exiled to a stone, guarded by a dragon, i.e. the winter, and that a knight, as spring, rescued her. The fact that these battles are often fought out in darkness or under the earth strengthens our hypothesis. For the Troytowns are regularly connected with the tradition of an {31} imprisoned and rescued maiden, as has been briefly mentioned above for the Visby design, where the maiden actually appears as the builder of the maze. That she was kept prisoner under the Galgenberg, just as other Troytowns lie in the neighbourhood of Galgenbergs, again points to a pre-Christian origin and a subsequent satanization.

Fig. 2

The numerous German traditions of the dragon-fight for the maiden may no doubt be assumed known, likewise the stories.

The best-defined is the legend of Siegfried with the fight against the dragon, the entry into the stronghold, and the

release of Brynhild from her magic sleep. In the oldest form of the Greek legend of Troy, Heracles kills the dragon

before the gates of Troy and rescues Hesione. Likewise Perseus rescues Andromeda from a sea-dragon. Theseus overcomes

the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth. He extricates himself from its false turnings with the help of a ball of thread

that Ariadne has given him. Frobenius also reports a fight against a dragon in his tales from Kabylia in Algeria

(Atlantis 2, p. 183 No. 20). Here the dragon-killer remains standing inside the pavement. He kills

a second seven-headed dragon by the sleeping maiden in a castle (thraja). The ball of thread is here divided into a

black and a white, which two men wind backwards and forwards to produce night and day. According to a Bulgarian legend

Sir George again fights with a dragon before the gates of Troy, as he wishes to free the maiden.

As a folk-custom the fight with the dragon is perpetuated today in Germany, Austria, England and France. Often there is connected with it the freeing of a maiden, known as the May Queen, etc. Even the bathing in dragon’s blood survives in a weakened form; for in some of these customs people try to soak up the streaming “dragon’s blood” with cloths. How old these games are is evident from 14th-century manuscripts that mention the wurme spil (dragon game). At the beginning of the 15th century the schoolchildren of Magdeburg were forbidden to play the ludus draconis. And if Hans {34} Sachs writes a new text for the dragon play, this is made to conclude with a singing of the old one. And that lasts for a very long time. Particularly often the legends and customs involve the appearance of St George, who is however nearly always known as “Sir” George. The festivals are frequently celebrated on his day, the 23rd of April. And it can be assumed at once that the May games, May dances, riding round the Maypole, and the choice of the May king and queen have a close connexion with his festival. Often the introduction of Christian feast-days in place of the old ones is to be blamed for the displacement and disruption of the festivals. Often also the change to the present calendar. However, there are many indications that the beginning of May had twelve holy nights, analogous to the New Year. What is now called “Old May Day” ends with the three ice-saints, just as in winter the twelve nights end with three holy kings„ So it is possible that all those games were part of a single whole, which began with St George’s day and was enacted in and around the Troytown. Now Krause links the May dances in the Troytown with the morris dances. Indeed the region where these dances are at home is the countryside around Whitby in Yorkshire. But St Maurice (= morris) has his day on 22 September. Nevertheless morris dances can be connected with Troytowns to this extent, that Maurice and the dragon-fighter Michael (29 September) are the winter counterparts of Sir George. Just as the latter releases the sun in springtime, the two autumn saints take it into their care at the end of summer. The opposition between summer and winter expresses itself through many customs and traditions. Thus Shrove Tuesday and Kirmis customs are similar, and the fir-tree at Christmas corresponds with the May Tree and the Whitsuntide Birch. Further, the old calendar signs on the Gallehus horns would also agree with this, for they show May by a snake stretched full-length, and autumn by one coiled into a spiral. St Quentin also had his day in {35} autumn, on 4 November.

Perhaps the shells with which the Narros decorate their hats are connected with Troytowns, which are also known as “snails”; likewise the eating of snails customary during many popular festivals. St Benedict’s day, 21 March, is also connected with the Troytown, for in the rural calendar his symbol is a spiral emerging from a bowl decorated with nine semicircles. Nowadays it is reinterpreted as a bishop’s staff.

It may also be observed that the late middle ages used the Troytown as a symbol of human behaviour and character. At least those portraits which show a maze on the subject’s breast, as embroidery or an ornament, can hardly mean anything else. The hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that occasionally the person in the painting clearly points to the labyrinth with a finger.

The only surviving Troytown in Germany, as far as I know, is that at Steigra, a village between Querfurt and Freyburg an der Unstrut. It has remained in existence to the present day (1935) because every year about Easter the villagers cut out the rings afresh. Just as the Troytown preserved in the arms of Graitschen is supposed to be a memory of Swedish rule, so the one at Steigra is called “Schwedenring”, although in both cases it is quite certain that an origin in the Sweden of Gustavus Adolphus is out of the question. Of the customs once practised here no memory is left. But it is not wrong to restore the customs belonging to this spot by reference to other similar layouts. And it is a striking fact that in the region around Steigra, out as far as Merseburg, Sir George plays an important part. There are many representations in churches of the knight and his fight against the dragon. A much-weathered one is also situated on the Querfurter Berg. The church at Steigra is dedicated to St George, and the inn bears the name “At the Sign of {36} Sir George”. If we consider the custom mentioned above, of recutting the rings at Easter, we may readily conclude that here too a spring festival was once celebrated. However, though there is no more information available about the customs and games for which the Troytown at Steigra was once used, there is still good reason to thank the village for the steadfast loyalty with which it still protects and cares for its maze, thereby preserving this unique prehistoric monument into our own time.