Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1879, 180–183

This paper was chosen to go with the statistical study by Forrest & Behrend.

{180}

The “Devil’s Arrows,” Yorkshire.

By A. L. Lewis, Esq., M.A.I.Member of the Anthropological Institute

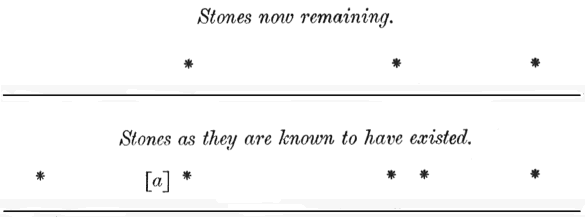

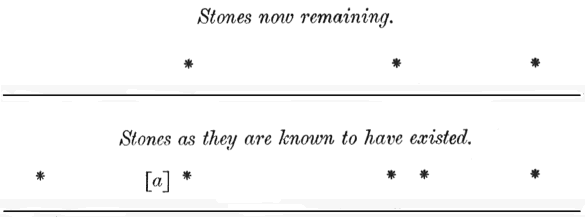

Near Boroughbridge, about 15 miles north-west of York, are situated certain stones, known as the “Devil’s Arrows,” at the present time three in number. They stand in a line nearly north and south by compass, the most northerly being about 18 feet high, 7½ feet broad, and 3½ feet thick; 197½ feet from this is a second, about 22 feet high, by 4½ broad and thick; and 362 feet farther, standing nearly on the brow of a slight hill, is the third, about 23 feet high, by 4½ broad, and 4 thick.

Camden, Leland, and Stukeley speak of a fourth stone, which, by putting their descriptions together, may be supposed to have stood between the first and second, and close to the latter. Leland says they stood within 6 or 8 feet of each other. Stukeley says two of the stones are exactly 100 cubits apart, and 100 cubits, at his standard measurement of 20¾ inches to the cubit, equal 172 feet 11 inches only, against about 187 according to my measurement (197½ feet, less 4½ for the thickness of the lost stone, and 6 feet for its distance from the second existing one). He says further, that two more stones, doubtless my second and third, are 200 cubits asunder, that is 345 feet 10 inches, instead of 362 as measured by me. Again, he says in an unpublished letter, that another stone, now (1740) carried off, was 100 cubits more, in the whole making 400 cubits distance. {181} This stone would obviously be in prolongation of the present line southwards. It will be seen that there is a considerable difference between Stukeley’s measurements and mine; but I am not the only one who has had occasion to differ from him as to facts and details concerning these monuments, and after comparing a number of his measurements, given both in feet and cubits, I have come to the conclusion that the feet represent his view as to the actual measurement, and the cubits his view as to what the distance was intended to be or ought to have been. That his cubits were only approximate in the present instance may be judged from the fact that even if we suppose his 100 cubits, 200 cubits, and 100 cubits, making in all 400 cubits, to be taken from the centre of the stones, so as to omit their thickness, the distance between the lost stone and the second existing one, and half the thickness of both these, say 10 or 12 feet in all, must either be added to his 400 cubits, or subtracted from the 100, the 200, or the second 100 cubits.

The arrangement of the stones past and present will be understood from the following diagram:—

The next points for consideration are naturally the probable date and object of this monument.

The Rev. W. C. Lukis, whose opinions on rude stone monuments must always command the most respectful attention, and to whom I am indebted for valuable information respecting these very stones, read a paper before the Society of Antiquaries, a short time ago, in which he suggested that the stones were the remains of a series of lines, like those of Carnac, a view which I do not at present see sufficient reason for adopting. A series of avenues of stones at an ordinary distance from each other, and extending more than 700 feet in length, and a proportionate breadth, would require some hundreds of stones, none of which would have been very small if we may judge from those left, and I cannot believe, without further evidence than is afforded by the known destruction of two stones in two centuries, that {182} all these would have been removed, leaving no trace behind except the three survivors. Mr. Lukis, informs me, however, that he is going to survey the country round thoroughly, to see if he can find any indications of other stones, and it is but right to wait the result of his search before giving a final opinion on this question.

While contending stoutly for the pre-Roman and probably Celtic origin of the stone circles and dolmens of our country, I should be disposed to listen favourably to any evidence that might be brought forward for a Scandinavian authorship for the “Devil’s Arrows.” There seems to be some reason to believe that the Scandinavians did erect stones in commemoration of battles, and there is no part of Britain in which we might more expect to find such a Scandinavian monument than in Yorkshire. The monument, as it is known to have stood, is very nearly symmetrical, and of a very different character from those which I have always held to be British; the addition of a single stone at the point marked [a] in the diagram, would make it perfectly symmetrical, by matching the two stones which are known to have stood close together, but those two might have been placed so to mark some special point in the battle (if battle there were), and I do not therefore insist upon the existence of even one other stone. I am not aware that any sepulchral deposits have been found here. If so they would perhaps settle the date. If not, it might be inferred that no battle had taken place here.

The stones themselves are of a soft grit, full of tiny pebbles, and the rain has worn long and deep channels on all sides of them, narrowing from the top downwards. These channels have been mistaken by at least one antiquary for artificial “flutings,” but that they are waterworn channels is evident from their running straight down two slanting sides of a stone which leans, and from their being very long on the uppermost (third) side, and very short on the overhanging (fourth) side of the same stone.

These stones being of great size, questions naturally recur as to the means by which they were carried to and erected on their present site, and I may therefore be excused for repeating an account which I have received, but have never seen in print in this country, of the manner in which these things are done by some of the hill tribes of India.*

* This account was given by Mr. Greey, C.E. (since deceased) to the late Dr. Inman, who sent it to me for publication. I sent it to the “Materiaux pour l’Hisioire Naturelle et Primitive de l’Homme” (April, 1876), but have seen no notice of anything of the sort in English.

A stone having been selected from some place where there {183} are natural cracks, into which levers and wedges may be introduced, is split from the parent rock by those instruments, and moved on rollers till its weight is transferred to two or three straight tree trunks cut for the purpose, under which strong bamboos are placed crosswise, which again rest on a number of smaller bamboos, and these again upon others, if the stone be very large, the smallest being far enough apart to allow a man to stand between them. All these being lashed together at each crossing, form a simple but substantial framework, which may be made of such size as to allow a sufficient number of men to grasp, lift, and transport it and its burden, so that a stone weighing twenty tons has been known to be carried up a hill 4,000 feet high in a very few hours. It has been calculated that three or four hundred men, could in this manner transport either of the “Devil’s Arrows” any distance that might be wished.

On reaching the spot where the stone is to be erected, a hole is dug of sufficient depth to keep it steady, into which one end of the stone is allowed to slide, ropes are then attached to the framework, on which the other end still rests, and by hauling at them the stone is quickly set up.

These operations, based as they are upon a sound natural principle, are yet so simple and so well suited for a state of society in which unskilled labour is very plentiful, that we may readily believe them to have been carried on in our own country. There might be some difficulty in getting a stone perfectly perpendicular in this way, and that may be one reason why so many are found leaning, and why so many others, which were doubtless more or less upright in the first instance, have fallen altogether.