The title of this presentation is, perhaps, provocative. There ought to be a question mark after it, as indeed there ought to be a question mark after all attempts to explore ancient mysteries. The author therefore again emphasises that his attempts at contributing to some further glimmer of comprehension in regard to the puzzles of the past necessarily involves the element of speculation. Having posted his disclaimer he now invites your company on his journey.

The journey begins in Egypt and ends in England. “Why doesn’t it begin in England and end in Egypt?”, you may ask. Well, I’ve already offered an hypothesis that early cultures first flowered in the Tropical Zones because of extraterrestrial intervention due to contact from within the Solar System (Ref. 1), and I’ve got to face the fact that some of the most impressive of the early monuments manifesting a high degree of organization and possibly astronomical knowledge were raised in England. So it would be personally satisfying (and might even contribute to science) if there were links between Egypt and England that commenced in Egypt.

The pyramids at Giza represented the pinnacle of Egyptian pyramid building. The latest historical dates for the Fourth Dynasty cover the interval from about 2565 to about 2440 B.C. These dates can not vary widely because of archeological synchronisms with Palestine and Mesopotamia in that period (Ref. 2). The earlier step pyramid at Saqqara is Third Dynasty for which a date of about 2686 B.C. has been assigned (Ref. 3). The major Egyptian pyramids may therefore he dated with some confidence to the period commencing about 2700 B.C.

Modifications to the method of radiocarbon dating based on bristlecone pine studies have had a significant influence on the dating of early monuments in Europe and elsewhere (Ref. 4). For the monuments in England we shall be considering below, the central date now assigned for the construction of Stonehenge I is 2775 B.C. and for Silbury Hill is 2745 B.C. (Ref. 5). As pointed out by Ivimy, if the above dating techniques are accepted these constructions are contemporary with, if not slightly earlier than, the early Egyptian pyramid-builders in Egypt.

The classic diffusion hypothesis of Elliot Smith (see Ref. 4) postulated the migration of culture bearers from Egypt. My own hypothesis postulates the migration of culture bearers from selected extraterrestrial contact areas in the Tropical Zones, with major source regions being located in North Africa around the Tropic of Cancer, and certainly including Egypt (Ref. 6). Elliot Smith’s diffusion hypothesis has long been a subject for dispute among anthropologists. My own hypothesis, should it succeed in attracting any attention from them at all, may not be immediately accepted.

When I examine the dates quoted above for some measure of assurance, I don’t really find it. However, it seems to me that the door to further developments is ajar. The bristlecone pine data is probably not the final source of dating for the period. As that which is not precluded must be treated as possible, we will proceed with our adventure. At some future date we must be prepared either (a) to quietly forget the whole thing or (b) to enjoy the recollection of our prescience.

In planning a pyramid there are two basic decisions to he made in fixing its size and shape. For the classic Egyptian pyramid the factors are the height and the length of the sides at the base. This then fixes the slope of the faces of the pyramids. The circular mound with a flat top at Silbury Hill in England, the largest prehistoric man-made mound in Europe, is essentially a pyramid also. The important dimensions to be fixed are the height and the radii at the top and at the base, here fixing the slope of the curved surface. The horizontal dimensions could be marked out using a rolling drum as suggested by Connolly (see Ref. 7). This could account for the supposed early knowledge of the value of “pi”, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter.

I noticed a series of apparent geometric relationships between some of the Egyptian and English monuments in a sequence of notes published in The News, now the Fortean Times (Refs 8, 9, 10). In case anyone read these exercises I should record that I have abandoned one of my speculations and modified some of the others. I have abandoned my consideration of the significance of one of Watkins’ alignments through Stonehenge as pointing to Giza mainly because I have a lessened persuasion of the significance of his ley line.

My attention was first drawn to this field of study when I realized that the slope of some of the major Egyptian pyramids, about 52 degrees, corresponded closely with the latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere of some of the major English monuments, i.e. Avebury, Silbury Hill and Stonehenge, all of which lie between latitudes of 51 degrees and 52 degrees North. After I had submitted the first draft of my article to Bob Rickard I acquired a copy of Ref. 5, which had just been published, and saw that Ivimy had discussed the matter in some detail. I therefore incorporated a reference to Ivimy’s studies in the article as published. Not only was Ivimy in there first, but he was first with the mostest. I returned to the problem with renewed zeal.

A diagram of Silbury Hill (Ref. 11) showed a slope of 30 degrees. Here was something of a clincher: 30 degrees is almost precisely the latitude of Giza. So the reciprocal relationship also applied. The pyramid slope at each latitude represented the latitude of the related pyramid (well, quite closely).

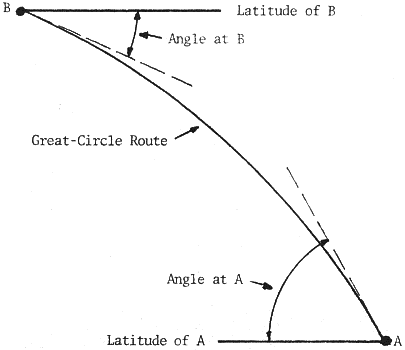

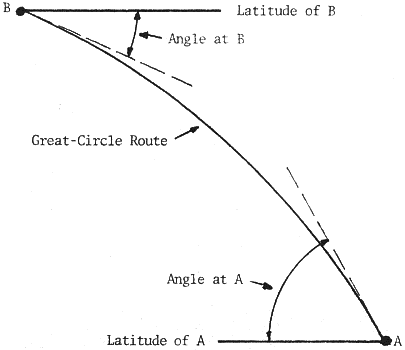

In considering the significance of Watkins’ ley line I had stretched a thread on a globe between Stonehenge and Giza to check the correspondence of the ley line with the direction of the great-circle route between the two locations. It is difficult to check angles on a spherical surface with a protractor, but a rough check showed that the great-circle route made angles at each end of the route with the local parallel of latitude of 29 degrees at Stonehenge and 52 degrees at Giza.

The numbers had a familiar ring about them, and a colleague of mine, Captain William W. Bull, was kind enough to check the data on a navigation chart plot. Within the limits of error of the method, the numbers appeared to look quite good. I felt encouraged to continue.

At my request, Dr. Michael A’Hearn of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Maryland furnished me with details of a computational method for determining the angles with improved precision. When I applied the method to the Giza–Stonehenge great-circle route I was rather disappointed. The correspondence of angles was within 1 degree at Giza and within 2 degrees at Stonehenge. It is just a feeling in my bones, but while 1 degree doesn’t seem too bad, 2 degrees seems rather too large for a significant relationship. I decided to move a bit further afield from these locations.

I realized that if I moved North from Stonehenge or South from Giza (or both moves simultaneously) I could get the margin to narrow. I settled on Avebury to the North of Stonehenge and Meydum to the South of Giza as my alternates. Silbury Hill is just South of, and close to, Avebury and so results applying to Avebury may also he applied to Silbury Hill in this context. Avebury was selected because it is the site of a great stone ring, and Meydum was chosen as it is the site of the first of the pyramids initially having a slope of about 52 degrees.

When the angle correspondence was examined for the extreme of those cases, the Meydum–Avebury great-circle route, the correspondence was within one-tenth of a degree at Meydum and one-fifth of a degree at Avebury. Perhaps we had a Meydum–Avebury connection instead of a Giza–Stonehenge connection. Moreover the slope of about 52 degrees for the pyramid at Meydum was fairly close to the latitude of Avebury, about 51½ degrees, while the slope of Silbury Hill near Avebury was fairly close to the latitude of Meydum at about 29½ degrees.

We don’t know the true initial slope of the pyramid at Meydum as it is now in a state of disrepair following the collapse of the outer casing (Ref. 7). And Silbury Hill is a much-weathered mound, so its true initial slope is also unknown. Inspection of photographs suggests a present slope slightly less than 30 degrees.

As a basis for further investigation we here postulate a Meydum–Avebury connection, with Giza and Stonehenge as proximate but associate or secondary sites. Of course, this calls for a further look at the whole question of dating. Perhaps it would be too outrageous to suggest that the close relationships outlined above may assist in the establishment of the relative dating of the monuments considered, so we’ll stop just short of doing so.

I noticed that the Tor at Glastonbury in England, a natural mound rising from a surrounding area of land that is comparatively level, appeared to be oriented with its axis pointing toward Avebury. Glastonbury is an ancient place of worship strongly associated with early Christian tradition in England. The angles calculated for the great-circle route between Glastonbury and Avebury were about 28 degrees at Glastonbury and 27 degrees at Avebury. John Michell refers to the alignment of the Tor with the direction of Avebury in Ref. 13, and suggests that the Tor appears to have been artificially shaped for this purpose. The alignment may support the emphasis on Avebury indicated in the present treatment. It may be noted that the angle of 27½ degrees at Avebury corresponds to the angle made by two of the openings in the reconstruction of the Avebury circle illustrated in Ref. 14.

Last, but not least, I would like to refer to the work of Nigel Pennick (Ref. 15). Among other relationships he has examined the location of the so-called “Zodiacs” close to latitude 52 degrees North in Britain. The world of the past breathes mystery and beckons our involvement.

| A | B | Latitude of A | Angle at B | Difference | Latitude of B | Angle at A | Difference |

| Giza | Stonehenge | 29.98 | 28.18 | 1.80 | 51.17 | 50.35 | 0.82 |

| Giza | Avebury | 29.98 | 28.50 | 1.48 | 51.42 | 50.75 | 0.67 |

| Meydum | Stonehenge | 29.39 | 28.89 | 0.50 | 51.17 | 50.94 | 0.23 |

| Meydum | Avebury | 29.39 | 29.20 | 0.19 | 51.42 | 51.34 | 0.08 |

| Glastonbury | Avebury | 27.35 | 28.01 |

The author wishes to thank Captain William W. Bull, Assistant Professor of Aerospace Studies of the AFROTC, University of Maryland, for his plots on a Lambert Conformal Chart, and Dr. Michael A’Hearn of the Department of Physics and Astronomy for details of the computation method for determining angles made by great-circle routes.

| 1) | Stuart W. Greenwood, “Extraterrestrials and the Tropical Zones”, The INFO Journal, May 1974, pp 19–21. |

| 2) | Gus W. Van Beek, Curator – Old World Archeology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Personal Communication, 29 March, 1974. |

| 3) | I. E .S. Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt, Pelican Books, 1947. |

| 4) | Colin Renfrew, Before Civilization, Knopf, 1973. |

| 5) | John Ivimy, The Sphinx and the Megaliths, Turnstone, 1974 |

| 6) | Stuart W. Greenwood, “Giza: Extraterrestrial Focal Point?”, Ancient Skies, March–April, 1975, pp 1–2. |

| 7) | Kurt Mendelssohn, The Riddle of the Pyramids, Praeger, 1974. |

| 8) | Stuart W. Greenwood, “Pyramid Slope and Northern Latitudes’’, The News, April, 1975, pp 12–13. |

| 9) | Stuart W. Greenwood, “On the Slope of Silbury Hill”, The News, December, 1975, p 6. |

| 10) | Stuart W. Greenwood, “The Giza–Stonehenge Connection”, The News, April, 1976, pp 14–15. |

| 11) | Andrew Davidson, “Silbury Hill”, paper in Britain: A Study in Patterns, a publication of the Research into Lost Knowledge Organization, 1971. |

| 12) | Janet and Colin Bord, Mysterious Britain, Doubleday, 1973. |

| 13) | John Michell, The View over Atlantis, Ballantine Books, 1972. |

| 14) | Jacquetta Hawkes (Editor), Atlas of Ancient Archaeology, McGraw Hill, 1974. |

| 15) | Nigel Pennick, “The Geomancy of the Nuthampstead Zodiac”, Stonehenge Viewpoint, First Quarter Issue, 1976, pp 7–9. |