View larger image

View larger image

{165}

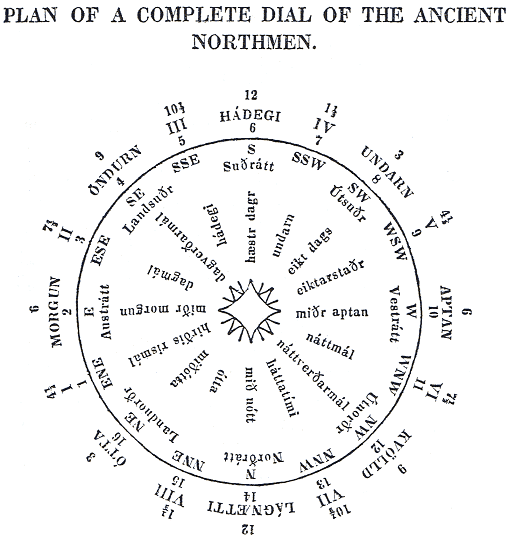

IT is well known that the ancient Scandinavians, like the modern Icelanders, divided the heavens or the horizon, first into 8 grand divisions, of which the middle points were named as follows:

| S. | suðr, South; | N. | norðr, North; |

| SW. | útsuðr, Southwest; | NE. | landnorðr, Northeast; |

| W. | vestr, West; | E. | austr, East; |

| NW. | útnorðr, Northwest; | SE. | landsuðr, Southeast; |

and, secondly, into 16 minor divisions, each of the grand divisions being bisected into equal portions by intervening lines, midt á milli. One of such grand divisions was called átt or ætt, the term being with great plausibility explained to signify an eighth part, and being supposed to have its derivation from the numeral átta, common to all the Germanico-Gothic, nay also to the Graeco-Latin and Persico-Indian languages. The word átt is still in common use in Iceland for such a division or aliquot part of the heavens, and likewise in Norway; where, however, as in days of yore, it is still written ætt.

Formerly the Scandinavians divided the times of the artificial day, dagr, (or of the natural day, dægr) according to the sun’s apparent motion through the above mentioned divisions of the heavens. They supposed that the sun percurred each of the grand divisions in 3 hours: so that on this supposition they divided the times of the day into as many corresponding portions as amounted to {166} 8 in each natural day, nycthemeron. Such a portion of time they called eykt or eikt (eicð, eykþ, öikt), which word has also been traced, through átt, to the numeral 8, and is likewise explained to signify an eighth part [166.1]. This eikt, or aliquot part of the day, was again divided, like each of the grand divisions of the heavens, into two smaller and equal portions, to which they gave the name of stund [166.2] or mál [166.3].

In order to know and settle those divisions of time, the inhabitants of each place carefully observed the diurnal {167} course of the sun, and in as far as this could be done, they accurately noted the terrestrial objects over which it seemed to stand when in each of the above mentioned celestial points; cf. Henderson’s Iceland I, 186.

In Norway, Iceland and the Ferroe-Isles, all of them mountainous countries, it was in general easy to find crags, hills, rocks, cascades, reefs, or to raise pyramids etc., whereby fixed points were obtained for each time of the day. Such natural or artificial objects were in Iceland called dagsmark, in the Plural dagsmörk, daymarks, or marks for such aliquot parts of the day. In Iceland each separate farm or estate had its own daymarks. The same was also in former times the case in Norway, where it still prevails to a certain extent among the common people, for example in Söndfiord in the West of Norway and Diocese of Bergen, from which district came the earliest inhabitants of Iceland, and where the names of the celestial points or divisions of the horizon agree with those of Iceland and the Ferroe-Isles. On this subject, Arntz [167.1], the most minute describer of this district, remarks (after having enumerated the 8 aliquot portions into which the inhabitants divided the day): “It is by marks on the hills and dales that the above mentioned times of the day are known. There is seldom much discrepancy between their noon and that shewn by the clock.” This last remark will in general hold good in the case of the daymarks of Iceland and of the Ferroe-Isles.

As the word dagsmark (singularly enough) is omitted in the only serviceable Icelandic Dictionary which we as {168} yet have [168.1], we shall here quote concerning it the following passage from Olafsen and Paulsen’s Journey (1772 Part I, p. 40), “The oldest and principal division of time has been found out by the course of the sun, and the cardinal or main points of the horizon. The primeval inhabitants of the country understood at all events to divide it into 8 equal portions and called the intersecting points dagsmaurk or daymarks.” The subsequent account given by the authors is, in point of reasoning, somewhat confused, inasmuch as they had found in different places the daymarks either double or not settled uniformly, and were not then aware of the true cause of this, which we shall forthwith proceed to unfold. Their accounts of the individual position of certain daymarks, however, particularly in the interiour of the country, which has longest retained the old customs, are very remarkable, and will in their proper places be noticed by us in what follows.

There can be no doubt, and indeed it follows as a consequence of the remark of the authors above quoted, that the most ancient inhabitants were originally led to fix the daymarks by a division of the horizon according to the principal winds; “as is the general opinion in the country itself. But they were also guided”, as they go on to say, “by the wants of their domestic economy, a circumstance which we have had occasion to remark during our journey almost every where throughout the interiour of the country, where the daymarks have not as yet been altered either according to the compass or sundial”. Con-{169}fusion was, however, gradually introduced in many places, particularly during the Catholic times, by the daymarks or their appellations being altered so as to adapt them to the Mass hours (horæ canonicæ), whereby in some instances the primeval words and significations were forgot, and in others new appellations were introduced. The Calendars published by Bishop Theodorus Thorlacius at Holum in 1671 and at Skalholt in 1692 seem also to have contributed much to this confused state of things by the incorrect names given in them for some of the times of the day and hours of the clock. The old way of counting time was notwithstanding maintained undisturbed in many places, while in others, the ancient names of the several Eikts or Stunds were entirely forgotten, and were only partially supplied by other incorrect ones. The names of the Eikts and of the Stunds became confounded with each other, and there was in this way formed a new and incorrect system, which now-a-days in colloquial intercourse has to a considerable extent got a fixed footing in the country, particularly in some maritime districts where clocks and compasses are in use: so that for example, dagmál is there put down for 9 o’clock instead of the half past 7 of the ancient Icelanders: náttmál, on the other hand, is put down for 9 o’clock p. m. instead of the ancient half past 7. In certain places, however, the inhabitants could not agree about this, insomuch that in such places, as Olafsen remarks, they got 2 different dagmáls, or marks for the same.

This is a circumstance which has given rise to some disputes among modern scholars as to the correctness of the different ways of fixing the daymarks. The profound antiquary and lawyer Paul Johnson Vidalin, Lagman or superiour judge of the southern and eastern district of {170} Iceland (born 1667, died 1727) who travelled on royal business throughout every parish in the whole country, and who accordingly was likely to possess the greatest imaginable local knowledge in regard to such matters, was the first who brought this literary dispute on the carpet, in one of his many commentaries which he composed chiefly in Iceland itself on certain expressions in the ancient laws of the country. The treatise in question was explanatory of the law expression “Allr dagr til stefnu”, and accordingly bears that title; but hitherto no complete edition of it has been published. A very short abstract of it, which merely exhibits the general result, may be found along with many others of a similar nature in the Transactions of the Royal Literary Society of Iceland vol 2, (1782, p. 113, 114). It is said that on this subject Vidalin wrote another separate treatise, but with which we are not acquainted; an abstract of them both, and, as it would appear, a very complete one, is to be found in the work of the celebrated scholar Bishop Finn Johnson, entitled Sciagraphia Horologii Islandici, tam veteris quam novi, p. 56, 58.

A contemporary of the lawyer Paul Vidalin, viz. John Arnason, Bishop of Skalholt (born in 1664, died in 1743) who certainly was deeply versed in theology, foreign ecclesiastical history and ecclesiastical computation, but who at the same time could not otherwise than acknowledge Vidalin’s profound and certainly very superiour learning in every thing that concerned the traditions of the country , took nevertheless several opportunities to impugn sundry of his opinions, and especially his opinion on this subject; about which he composed a separate treatise called “Eyktamörk, or Horologium Islandicum,” which however, first appeared in print as an appendix to {171} his Fingrarím or Dactylismus Ecclesiasticus Copenh. 1739, 12° p. 315. It was again published at the same place with a Latin translation, as an appendix to the ancient Rímbegla and Blanda (two Icelandic works of astronomical computations from the middle ages, here united) 1780, 25 p. in 4to. The author attempts to prove that our forefathers in general reckoned the natural day from the commencement of the night at 9 o’clock p. m.; and further that all the Icelandic daymarks, as now used and received in the maritime districts, are the same as they have always been: but his erroneous views of this matter have been completely confuted by the aforesaid Finn Johnson, partly in his above mentioned work, which has likewise been published as a second appendix to Rímbegla 62 p. in 4to; and partly previously, but in a shorter and less complete form, in his classical work Historia Ecclesiastica Islandii Tom. I, 1772 p. 153–157; wherein are, however, to he found occasional important remarks, which may help to supply the deficiencies of the separate treatise. Professor Rafn has inserted the whole of the passage hereunto relating into his Antiquitates Americanæ p. 435–438 referring at the same time to the same author’s Sciagraphia, (p. 5, 23–26, 56–58). Finally Finn Johnson has quoted and explained several passages hereunto relating in the ancient MSS in his separately published work: Tractatus historico-theologico- criticus de Noctis præ Die naturali prærogativa, aut dubia aut nulla. Hafniæ 1782, 8vo.

To Finn Johnson’s Sciagraphia we must also refer our readers in all the essential points, since in the main we perfectly coincide with the representation of the times of the day given there in pages 24–27 according to the system of the ancient Scandinavians. We shall by and by, in the course of the present article, ex-{172}hibit a view of this in a tabular form, compared with the corresponding way of reckoning time prevalent among the peasantry of Norway, and more especially those of the Ferroe Islands, with which neither Paul Vidalin nor Finn Johnson were acquainted; although it is precisely here that we find the clearest proof of the correctness of the views given by them, and especially by the last mentioned, the more so that the inhabitants of the Ferroe-Isles have scarcely at any time had any direct communication with the Icelanders, and can by no means be supposed to have borrowed their chronometrical scale from them: but on the contrary each people must have brought it from their common aboriginal land Norway.

According to Finn Johnson’s laborious and profound investigations the ancient inhabitants of the North made the working day or civil day commence at the first rising time as fixed by the ancient codes of the country Grágás and Jónsbók, viz. the shepherd’s rising time, called hirðis rismál, which was at half past 4 o’clock, and which down to this very day has continued to be the rising time of the workpeople in the hay making season. The passages of the law above alluded to, however, owing to a form of construction which in our days seems somewhat peculiar or obscure, have been understood in different senses by the interpreters. We are therefore under the necessity of quoting and elucidating their expressions.

First, then, in the Grágás (promulgated in 1118) in that section of it entitled Landabrigða-bálkr, Cap. V, it is enjoined a landed proprietor or farmer in certain cases (when for example several of his neighbours complained that his sheep had passed over into their grounds and in this way had damaged their pastures): Þá skal hann láta reka fèit í miðian haga sinn of apna. Hann skal {173} fundit hafa fè sitt, er sól er í austri miðju; þat heita hirðis rismál: that is: “He shall cause his sheep (or his cattle in general) to be driven to the centre of his own pastures every evening. He must have found (collected) his sheep (or cattle) when the sun is due East. This is called the rising-time of the shepherds.” On reading these words with attention (not merely running the two last clauses together and so taking the literal sense of the words) it will be obvious to every one that the meaning of the whole passage is this, that the farmer or his shepherd (or in general all shepherds) must rise so betimes in the morning as to be able to have found and collected his flock, when the sun in the morning was due East, consequently 6 o’clock. For the performance of this task we have allowed at the most an hour and a half; that is, a stund, or the half of an eykt, which in this way must have commenced at half past 4 o’clock, (at which time of the day, particularly in summer, it is still the practise in Iceland for shepherds and others to get up) and which was therefore called hirðis rismál. In pastures so extensive as those generally belonging to an Iceland farm, where in the course of a night’s roaming the flocks naturally get widely scattered, it is not to be supposed that the shepherd should be able to find and to collect his scattered flocks in a moment (viz. at the precise time of 6 o’clock). Our learned friend, the translator of this code, has not rightly understood the real import of the expression “skal hafa fundit” (shall have found), as he translates it merely by the single Latin word recolligat (pecora) [173.1]. Subsequently in the framing of the Glossary he has had occasion to take notice of {174} Finn Johnson’s mode of translating another passage taken from this law, or of a parallel passage in Jónsbók, and he has accordingly altered his own translation to the more correct one recollecta habeat (pecora). Yet be still persists in maintaining that it is the precise moment of 6 o’clock, which is signified in the law by hirðis rismál, where as it must necessarily be an earlier period.

The parallel passage in the later Code called Jónsbók [174.1], promulgated in 1280, is as follows: Þá skal hann láta reka í miðian haga sinn fè sitt um aptna. Hann skal hafa rekið það úr haga hins, þá er sól er í austri miðju, það sem hann mátti finna; það heita hirðis rismál, Landsleigubálkr, Cap. 16. The above passage is thus rendered into Danish in the printed translation of this Code [174.2]: “Da skal han lade drive sine Kreature om Aftenen midt udi sin Græsgang. Han skal have bortdreven af den andens Græsgang alt sit Fæ, som han kunde finde, naar Solen er midt i Öster, det hedder Hyrdens Opstaaelses Tid.” Or literally translated into English: “He shall let be driven his cattle in the evening into the middle of his pastures. He shall have driven out of the others pastures all his cattle, which he could find, when the sun is due East. This is called the shepherd’s rising time.” Finn Johnson makes the following comment in Latin on the true meaning of this passage: “(Lex) jubet opilionem tam mane surgere, ut armenta et greges heri sui, quæ nocturno tempore limites transgressa fuerant, ex vicinorum pascuis abegerit, i. e. hora VI, ok heita þat hirðis rismál, i. e. hoc tempus (non quo opus absolverat, sed quo sur-{175}gendum erat) vocatur opilionis surgendi tempus.” In the passage above quoted this Code conveys in more express terms the import (which, however, must also be ascribed to the Grágás) that the shepherd was to search for his sheep (or his cattle in general) not only on his own pastures or fields, but also in such as were situated in the grounds of several different neighbours. That an hour and a half would often be required for the completion of this task, is, therefore, more evident from the expressions of the later Code than from those of the elder one.

That the shepherds, to whom the passage in question chiefly relates, were wont in Iceland formerly (as is frequently the case now) to be up before the other people of the farm, may also be seen from the Sagas; for example Liósvetnínga Saga, Cap. 14.

Reckoning from this earliest rising time, or the beginning of the morning half past 4 a. m., the eighth stund (or eighth half eikt) elapses precisely at half past 4 in the afternoon, and therefore this period was called, κατ’εξοχηνPre-eminently, par excellence, eykt, the eighth stund (octona) in like manner as every eikt or aliquot part of the day had the same appellation, because it consisted of an eighth part (octava) of a whole natural day. This eighth, eykt, in question commenced strictly speaking at 3 o’clock, and ended at half past 4 p. m., in what was called the eyktar staðr, or the eykt’s place, limit or termination. The precise moment the sun appeared therein indicated the lapse of half the natural day, and was therefore held especially deserving of notice by our forefathers, the more so that, according to their way of reckoning, it also indicated the termination of the day proper and the commencement of the evening. That, excepting during the seasons of harvest {176} and haymaking, the working hours of the free people generally closed at that time, is very probable: but this is quite certain in the case of the holy eves after the introduction of Christianity. On which account in the Grágás, the oldest written civil Code, the expression eykthelgr (holy eykt) is employed in reference to saturday eve, and other eves then kept holy, most likely for this reason, that on such evenings all persons, both free men and thralls, were commanded to discontinue labor at the expiration of that eikt, or as soon as the sun appeared to be in the eiktarstaðr or eykt place as it was called. This did not correspond to the customs of other countries, in as much as the holy eve in this way commenced as early as 3 o’clock; wherefore the Bishops, as soon as a separate Churchlaw was framed for the country, got an adjusting clause introduced, namely the alteration that cessation from labour was not required to begin before half an hour later, viz. at half past 3, or the time that the daily mass of vespers called nona (from the hora nona of the Romans) was wont to he celebrated. This aliquot part of the day, therefore, or the time of 3 o’clock, got another name (of which more by and by) and was called nón; and the holy eves were now called in the churchlaws nónhelgir dagar (days kept holy after the time of nón). Yet there was partly retained in them the ancient name of the stund in question (from 3 to half past 4) viz. eikt; with this alteration that in regard to ecclesiastical matters it was shortened by half an hour: and (with reference to the people’s responsibility for desecration of a holy eve) it was considered as not commencing till half past 3. On this subject the following passage occurs in the 13 Chap. of the most ancient ecclesiastical Law of {177} the country [177.1]: Vèr skulum halda þvâttdag inn siöunda hvern nónhelgan, svâ at þá skal ekki vinna er eicð liðr, nema þat er nú mun ek telja. Þá er eicð, er utsúðrs ætt er deild í þriðiúnga, oc hefir sól gengna tvâ luti, en einn úgenginn; that is, “We must keep each seventh day holy from nón, so that when the eikt comes on (liðr), there must not be performed any other work than what I shall now enumerate. Then is eicð (commenced), when the South West division of the heavens or the horizon being divided into 3 sections, the sun has traversed two of these sections, but one is not yet traversed.” Here the Church law certainly says that Saturday is to be kept holy from the time of nón, viz. 3 o’clock p. m., but it does not adhere strictly to the precise hour, but allows the labourers half an hour to come and go upon, inasmuch as it fixes that the eikt shall not be considered as having commenced (in reference to the enjoined cessation from labour) until half past 3 o’clock, although it really commenced at 3. In consequence of this change, this stund has accordingly got the name of biskupa eikt, viz, the eikt regulated or altered according to the Bishop’s way of counting.

It is, however, the regular unabridged stund called by way of excellence eykt (of an hour and a half in duration) that is mentioned as follows in Grágás (Kaupabálkr Cap. V Part I p. 395), when treating of the payments of bonds falling due on a holy day or half holy day, Ef eycþhelgan dag er eindaginn, oc á maþr cost at stefna fyrir eycþ, en viþ skal hann taka, þótt viþ aptan gialdist, ef allr dagr var til stefnu; that is, “If the term of payment falls on a holy-eikt day, the creditor has a right to cite {178} (the debtor who does not pay) before the eykt commences; but he must receive the money even if it should be paid in the evening, in cases where the term day is no holy-day” (for in such cases the citation could be served up to sunset in summer, and to the coming on of darkness in winter). From this the obvious inference is that the Eykt, κατ’εξοχην, was the time or moment that most nearly preceded evening, which commenced precisely when the sun was in the eykt’s place (eyktarstaðr) [178.1] at half past 4 o’clock.

We certainly consider this explanation as of itself sufficiently clear; however, what we find said in Skálda of the daymark eyktarstaðr, or of the close of that aliquot part of the day called the eykt, according to the sun’s then apparent position in the horizon, is still more clear. The passage is worded as follows in all the ancient manuscripts, whether on vellum or otherwise, (in the enumeration of the seasons and the 12 months of the year in the ancient Icelandic or Northern Calendar): Frá jafndægri er haust til þess er sól setz í eyktarstaþ. Þú er vetr til jafndægris. – Haustmánuðr heitir hinn næsti fyrir vetur; fyrstr í vetri heitir Gormánuþr; that is, “From the Equinox is Autumn until the sun sets in the Eykt-place (at the end or close of the eykt). The month immediately before winter is called Harvest month, (Autumn month); but the first in winter Gor-month {179} (Slaughter month) [179.1]. Skálda was written in the southern part of Iceland in the 13th century, but the way of reckoning time here alluded to is much older, and derives from the heathen period. After Christianity was introduced, such computations were accomodated somewhat to the Julian Calendar, and whilst that Calendar remained in use, winter was considered as commencing about the 17th October. Bishop Theodor Thorlacius ascertained by astronomical calculations in his Icelandic Calendar (Skalholt 1692), that the sun set on that day at half past 4, consequently in perfect accordance with the statements given in Skálda and with the Eyktarstaðr as fixed by Paul Vidalin and Finn Johnson.

By way of distinguishing it from eykt in its more extended import, viz. the eykt of the natural day, the aliquot part of the day was expressly called eykt dags, that is, the eykt of a portion of the day. This expression occurs in several passages not quoted by any of our predecessors; for example in the fragments of the very ancient Heiðarviga Saga, which were long considered as entirely lost after the destruction of a valuable Vellum MS., containing the beginning of the Saga, which was consumed in the great fire of Copenhagen in 1728, together with a copy that had been taken of it. The celebrated Professor Arne Magnusson had borrowed it from Stockholm, where also another fragment, which contained the continuation and conclusion of the Saga, was discovered by the Icelandic Bishop Dr. Hannes Finnson (Johannes Finnæus) in 1772. It was in this latter fragment that the passages above alluded to were contained. In the most remarkable of them the author gives an account of an event, that happened in the summer of 1013, and in his narrative the following {180} circumstance is mentioned, that the harvest labourers on a farm in Iceland came home from work with their implements of labour at eykt dags, that is when the sun’s position was over that mark of the day. In other passages of the same fragment, the same time of the day is mentioned as belonging to the afternoon [180.1]. Yet in Norway. even during the heathen period, it was customary to call the stund without any distinction eykt; for example in Fornmanna Sögur Vol. XI, pag. 136. We may here remark that our much esteemed colleague, residing in Iceland, Sveinbiörn Egilsson, who may deservedly be looked on as one of the most profound scholars in the ancient language of the North, has explained this word in harmony with the acceptation given to it by the editor of the Antiquitates Americanæ; see Fornm. Sögur Vol. XII, in the Glossary.

Moreover Bishop Thorlacius, the calculator of the astronomical Calendar, fixes sunrise in the South of Iceland on the 17th October at half past 7 a. m., which again completely corresponds with the dagmál of the ancients as fixed by Vidalin, Finn Johnson and others; and thus it becomes perfectly clear that the expression applies to the very same time for sunrise in Vineland on the shortest day, and likewise that the expression eyktarstaðr applies to the time of half past 4 for sunset on the same day [180.2]. The counting of time by means of sun dials and hour glasses (or other vessels contrived for that purpose with sand or water, nay even watches and clocks) was most likely not unknown to the Northmen in the 11th century. After the introduction of Christianity such instruments naturally became indispensable for the use of {181} the clergy, since if they were not employed, many rules in the above mentioned astronomico-computistical writings Rímbegla [181.1] and Blanda would have been entirely useless. So far back as the earlier part of the middle ages, we find that clockwork, both for indicating time by hours and also for shewing the motions of the celestial bodies, was used among the Eastern Goths, Burgundians and Germans, who in general paid some attention to Arithmetic, Grammar and Astronomy, as is attested by both Cassiodorus and Dithmar of Merseburg. Even if we should not be disposed to admit that such knowledge existed among the ancient Scandinavians (which, however, their distant maritime expeditions as well as the express evidence of history [181.2] give good ground for admitting), still we must not forget that Vineland’s first discoverer, Leif {182} Ericson, who was born heir to the sway of the Northmen’s Greenland colonies, was brought up and instructed by the southern German Tyrker, and that Leif’s successor, Thorfinn Karlsefne, was not only descended from princely lineage, but had moreover educated himself by long trading voyages to countries of Europe at that time by no means barbarous, such as England, Scotland and Ireland, agreeably to the practise then so prevalent among the more wealthy Icelanders [182.1]. Of the Northern merchant’s {183} and shipmaster’s education in the middle ages, the reader will certainly be led to form a favorable idea from the Speculum Regale [183.1], as it was called, written in the 12th century. In this book the merchant is exhorted to make himself well acquainted with the laws of all countries, especially as regards commercial and maritime laws, and also with the languages of all countries, particularly the Latin and Italian, which were then the most generally diffused. He should also thoroughly understand the phases and the motions of the celestial bodies, the times of the day, the division of the horizon according to the cardinal and minor points, the movement of the sea, ebb and flood, the climates and the various qualities of the several countries thence arising, the seasons of the year best adapted to navigation, the equipping and rigging of ships, arithmetical calculations, the judicious investment of capital, etc. Moreover the merchant must distinguish himself by what according to the standard of those days was considered the most polished and decorous way of living, both as regards moral conduct and behaviour, and also manners, dress, the etiquette of the table etc. Whence it is easy to infer that the better educated among our ancestors in the 11th and 12th centuries were by no means so rude and ignorant as many southrons still imagine.

Before submitting to our readers the Table promised above, exhibiting a comparative view of the methods adopted by ancient and modern Scandinavians in the division and nomenclature of the points of the horizon and {184} times of the day, we think it fit to premise the following illustrative remarks.

The first main division of the Table exhibits in separate columns the order and number: 1, of each of the 8 larger divisions or aliquot parts of the natural day, or of the civil day, which formerly throughout the North (as is still the case in Iceland) was called eykt (eikð eikt, eycþ, öikt), and is still in the Ferroe Isles called ökt, in Norway ökt, ögt, and in some Swedish dialects ökn [184.1]; 2, of the 16 minor divisions of this cycle, which are still known in the two first mentioned countries, but seem to be forgotten in Norway. The Iceland statement corresponds accurately with the system so ably developed by Finn Johnson, which, it will here be clearly seen, is in every respect confirmed by the system still prevailing in the Ferroe Isles.

This Eykt- or Ökt-system we have taken from Landt’s attempt to describe the Ferroe Isles, Copenhagen 1800, 8vo, p. 443; wherein the following information is given of the inhabitants of the islands: “In regard to the division of the hours of the day, they know well enough, like the inhabitants of other countries, to divide the day into 24 hours, and have a tolerably accurate notion of the names belonging to each; nevertheless they have also their own customary method of dividing the day and naming its aliquot parts: and according to this method a natural day consists of 8 ökts, each ökt being equivalent to 3 hours; but for the purpose of indicating the time of the day {185} with greater precision, they have also half ökts, which consequently consist of an hour and a half each, to which they give names corresponding to the sun’s position, for example, ENE is called Halfgone East, i. e. ½ past 4 a. m.; E is called East, i. e. ½ past 6 a. m. etc.” a statement of which the author gives as far as the 13th division of the horizon and of the eikt. The three remaining concluding divisions we have taken from passages thereunto relating in Svabo’s Materials for a Ferroish Dictionary, which have not yet appeared in print [185.1]. From this source we have also given the names of the points of the horizon and of the stunds as used by the inhabitants of the Ferroe Isles in their vernacular or colloquial speech, which is well known to be a dialect of the Old-Northern, or, as it is now called, the Icelandic language.

The accounts we have of the national division of the day among the common people of Norway are of a scattered nature, and by no means so complete. In the large Danish Dictionary, published by the Royal Society of Sciences, which comprehends words of the dialects of the Norwegian peasantry, we find in the 4th Vol., Let. O. p. 17. “Ögt,– in the dialect of the Ferroe Isles and of Nordlands ökt, in Icelandic eikt, – a period of 3 hours. The Norwegian peasant still divides time into ögts”. It is doubtless these 8 ancient divisions of time about which Arntz (the author above quoted) in his Description of Söndfiord remarks, that they amount together to an ætmaal (or the 24 hours of the natural day. See page 167 above, Note 1). Some of them appear in later times to have got new names, and our author himself remarks that since the inhabitants have become accustomed to use the {186} printed Almanac, they have forgotten their ancient mode of reckoning time, and their knowledge of the stars. Nevertheless from what Arntz and others have stated, I have felt myself warranted in referring the said divisions of time to the ancient Norwegian Eikt-system, which follows precisely the same order in respect to the primary divisions of the horizon, and the enumeration of the times of the day.

The names of the points of the horizon, such as landnorðr for NE, landsuðr for SE., also útnorðr for NW. and útsuðr for SW. were evidently imported into Iceland and the Ferroe Isles at their first colonization from Western Norway; for both NE. and SE. were land winds, which blew across the land before reaching the coast; NW. and SW., on the other hand, were sea winds, which, agreeably to the ancient mode of expression, blew from without over the sea. In Iceland and the Ferroe Isles the first mentioned of these winds were considered as coming from the extensive sea coast of Norway, consequently from the great Scandinavian continent; the last mentioned, on the other hand, from the Atlantic Ocean or Polar sea, wherefore the ancient appellations were retained unaltered in the language. The table shews that these appellations, with a few trifling alterations so as to accommodate them to the modern dialects, have been preserved in the language of the common people both in the Ferroe Isles and also in the western and northern districts of Norway. Bishop Thorlacius, however, in his Calendar of 1692, p. 95–97, has not inserted them in Icelandic, in the enumeration of the principal winds, but on the contrary has tried to frame a new nomenclature for them, so as to harmonize better with the Danish, German, English, Dutch, etc., being nearly the same as what we now see delineated on the card of the compass, among most of the European nations. {187}

Formerly it was customary in Iceland at a very remote period – as is still the case in Norway – to designate the times of the day, or the stunds, by the sun’s apparent position above the points of the horizon. In the former land this is now entirely gone out of use. The half ökts, according to the division now in use, are, however, designated in Iceland in this way, that the sun (which is only understood) is said to be half way between miðmorgun and dagmál (midt á milli), or at an equal distance from both (jafn nærri báðum). The ancient word miðmundi or miðmunda is only used for one particular such daymark, viz. half past 1 o’clock p. m., instead of undarn – an expression now completely obsolete in Iceland.

{188}

| ALIQUOT PARTS OF THE NATURAL DAY. |

ASSUMED POSITION OF THE SUN. | NAMES OF THE VARIOUS TIMES OR PORTIONS OF THE DAY. |

HOURS. | |||||

| TERMS | TERMS USED IN | |||||||

| Eikt. | Stund. | now in use. | Iceland. | Ferroe. | Norway. | Iceland. | Norway. | |

| I | 1 | ENE | Midm. Ln. ok A. | Hålga [1] Estur. | — | Hirðis rismál [2]. | Solrenning [18]. | 4½ a. m. |

| 2 | E | Austr. | Estur. | Ouster. | Miðr morgun [3]. | Memorra [19]. | 6 | |

| II | 3 | ESE | M. A. ok Ls. | H. Landsuur. | — | Dagmál [4]. | För-Duur [20]. | 7½ |

| 4 | SE | Landsuðr. | Landsuur. | Landsör. | Dagverðarmál [5]. | Davremaal [21]. | 9 | |

| III | 5 | SSE | M. Ls. ok S. | H. Middag. | — | Hádegi [6]. | Hög Dag [22]. | 10½ |

| 6 | S | Suðr. | Suur (Middag). | Sör. | Hæstr dagr [7]. | Högst Dag [23]. | 12 | |

| IV | 7 | SSW | M. S. ok V. | H. Utsuur (H. Noon). | — | Undarn [8]. | Undaalen [24]. | 1½ p. m. |

| 8 | SW | Útsuðr. | Utsuur (Noon). | Utsör. | Eykt dags [9]. | (Ögt) Noon [25]. | 3 | |

| V | 9 | WSW | M. Ús. ok. V. | H. Vestur. | — | Eyktstaðr [10]. | Ögterdag [26]. | 4½ |

| 10 | W | Vestr. | Vestur. | Vester. | Miðraptan [11]. | Midefta [27]. | 6 | |

| VI | 11 | WNW | M. V. ok Ún. | H. Utnoor. | — | Náttmál [12]. | Natmaal [28]. | 7½ |

| 12 | NW | Útnorðr. | Utnoor. | Utnör. | Náttverðarmál [13]. | Naattvær [29]. | 9 | |

| VII | 13 | NNW | M. Ún. ok N. | H. Noor. | — | Háttatimi [14]. | Afdag [30]. | 10½ |

| 14 | N | Norðr. | Noor. | Nör. | Mið nótt [15]. | Högstnaatte [31]. | 12 | |

| VIII | 15 | NNE | M. N. ok Ln. | H. Landnoor. | — | Ótta [16]. | Otta [32]. | 1½ a. m.Not in the original |

| 16 | NE | Landnorðr. | Landnoor. | Landnör. | Miðótta [17]. | Ottemaal [33]. | 3 | |

{189}

| 1. | Hålga signifies halvgaaen, halfgone, used here with reference to the sun, as otherwise generally with reference to the time and the hour. |

| 2. | See 18. Here the morning commenced. |

| 3. | Midmorning (middle of the morning). See above p. 172–175, also called rismál, rising time, from risa, to rise, now obsolete in the Icelandic. |

| 4. | That dagmál is by the peasantry of Iceland still referred to this time, may be seen in the following books of travels: Olafsen, I, 40; Troil p. 90. Henderson (about 8 o’clock, for he never mentions half hours) Iceland I, 187. |

| 5. | Forenoon meal time: for other persons than travellers who took this meal earlier. |

| 6. | In most places of Iceland the peasantry still place this daymark correctly; see Olafsen’s, Troil’s, and Henderson’s accounts in the passage above quoted. |

| 7. | That is (like the corresponding Norwegian denomination) highest day. This very ancient term is still used by the peasantry of the West of Iceland instead of hádegi, which many now-a-days incorrectly refer to 12 o’clock. Biörn Haldorson’s Atli p. 47. |

| 8. | Now called miðmunda. Undarn occurs in Old-Northern MSS, both as afternoon, and also a meal or convivial party held at that time: see, for example, Rafn’s Krákumál or Loðbrokarkviða p. 2, 29, 96–97. In a similar acceptation for noon or afternoon, we found in Mœso-Gothic undaurn, in Alemannic (old High German) untorn, Anglo-Saxon undern: also in the old English of Chaucer, although the word was also occasionally used in Anglo-Saxon for a particular part of the forenoon; s. Note 9 and 24. |

| 9. | As this stund formed the latter half of the “Eikt” undarn, it is remarkable enough that the Anglo-Saxons called its close 3 o’clock p. m. heah undern; see note 8 {190} On the other hand the Catholic clergy in England called it non from the Mass Nona (belonging to the horæ canonicæ), which took place at the same time; whence the Old-Saxon non, Old High German nuon, Scandinavian nón; see note 25. |

| 10. | The word signifies the Eikt’s place (here termination or close). It was also called aptan or aptansmál, as the evening commenced here; see above p. 175–178 and notes 26, 27. |

| 11. | The middle of the evening (now called miðaptan in Iceland); see note 27. |

| 12. | That in most parts of Iceland this daymark is still correctly placed, is testified by Olafsen, Troil and Henderson at the passages above quoted. |

| 13. | The name denotes the evening meals time. |

| 14. | i. e. Bedtime. |

| 15. | Midnight. |

| 16. | The word corresponds to the Mœso-Gothic uthvo, the Alemannic uohta, ouht, ocht, uht, uchtenstond, the Netherland and Frisian ucht, Anglo-Saxon uht, uhtentid. See Rafn’s Krákumál or Loðbrokarkviða p. 12, 124, and note 32, 33. |

| 17. | The middle of the ótta; called also hana-ótta, the cock ótta; or hana-galan, cock-crowing; Anglo-Saxon hancreð; see note 33. |

| 18. | Sólrenníng, sunrise time; aabitsmaal is still known both in Iceland and in the Ferroe Isles: from ábitr, aabit, refreshment time in summer at the earliest part of the morning. |

| 19. | Also in modern Danish midmorgen, Swedish midmorgon, etc. |

| 20. | The earliest breakfast: corresponding to the Frisian vordard. This stund is also called in particular districts {191} of Norway frokostbeel; see note 21. Corresponding expressions to the ancient dagmál are also found in the dialects of the common people in modern Denmark and Sweden. |

| 21. | Called also daguur. The ancient dagurðr, dagverðr, has in the later dialects undergone the greatest alterations, for example it has become among the Norwegians dul for dur. Otherwise in Swedish it is dagvard, in Danish davre, daver, dover, douer, in Frisian daagerd, dauerd, daaerd, dard, etc.; see note 5. |

| 22. | To this there are sundry corresponding terms, in German, Dutch, etc.; see notes 6, 7, 23. In certain districts of Norway this portion of time was also called halvgaaet til middag. |

| 23. | Otherwise also hæsdag; corresponding to the Old-Northern term. See 22. |

| 24. | Called also ondol, ondolsmaal. Traces of the ancient undarn (ondarn) especially as applied to noon or afternoon meal time, midday sleep, etc. are to be found in the peasant dialects in Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherland and Great Britain: viz. in the last mentioned in aundern, ownder, onederin, orndors, orndinner, orn-supper, orntren, etc. |

| 25. | See above note 9. To this corresponds the British shepherd’s high noon as applied to 3 o’clock p. m.; the Bavarians non and the Westphalians none etc. still in use. On the other hand the English noon and the Dutch noen now signify midday, 12 o’clock. See Sir Henry Ellis’s Edition of Brand’s Popular Antiquities. I. 457–460. We have otherwise ground for supposing that down to the year 1700 the common people in Denmark called this stund ögt; see note 26. It would appear that several expressions among the German nations having reference to holy eves, and which are still in use among the common people, {192} are related to the eykt, or öikt of the Scandinavians: for example aecht in Suabia, ucht in Ditmarsch, etc. |

| 26. | Also ögterdags beel, ögtebeel. These and several other words which are of great importance in fixing the time of the day now in question, are to be found collected from the Danish and Norwegian Peasant Dialects in the large Danish Dictionary, 4 Vol. 3 Section, p. 17. O. |

| 27. | The Anglo-Saxons called this time of the day ofer-non, as the Norwegians in Telemarken still call it etter-ökt (for similar etymological grounds). To the Icelandic and Norwegian term there are several corresponding ones in Denmark and Sweden. |

| 28. | Among the Scandinavians the late part of the evening commenced here, called kveld, kvöld, cvylcwyld: in use in the modern dialects. |

| 29. | See note 13. |

| 30. | The word denotes the expiration or end of the day. |

| 31. | Literally the highest night. In some British authors we meet with the expression “noon of the night”. |

| 32. | This word is also used in the modern Danish and Swedish Dialects. |

| 33. | See above note 17. |

From a drawing executed by Eggert Olafsen, Biörn Haldorson (in a work entitled Atli, 3 edition, Copenhagen 1834, p. 45–46) has exhibited and explained a plan of a sun dial constructed agreeably to the view now given of the Iceland daymarks, as the only correct one; for the use of the common people of Iceland.

Footnotes

| 166.1 | From ætt (átt) or eykt comes undoubtedly the Danish and Norwegian word Ætmaal or Etmaal (the period of the 24 hours of the natural day) as the meted division both of the points or portions of the horizon and times of the day. It occurs likewise in the Frisian language in the form of aetmal, etmal, in Dutch etmaal. |

| 166.2 | Also in Anglo-Saxon, Danish and Swedish stund, in German stunde, in Dutch stond, in English and Scotch (though now obsolete) stound. When the times of the day began to be reckoned in the North according to the Roman or Catholic horary division, the word came at length in the Norwegian and Icelandic languages to signify one of such hours. Accordingly John Olafsen in the Glossary to his Syntagma de Baptismo, Copenhagen 1770, 4to, translates it by hora major sive minor. |

| 166.3 | In Danish maal; in Swedish and Ferroeish mål; in German mal, mahl; in Dutch maal; in Anglo-Saxon mæl, mel; in Mœso-Gothic mel. Hence (and not as many now-a-days imagine, the converse) the Oldnorthern mál, máltid; Danish maal, maaltid; Swedish mål, måltid; German mahl, mahlzeit; Anglo-Saxon mel, mælmete; English meal; Dutch maal, maaltyd. It was not only meals that were regulated according to such fixed times of the day, but also the time for milking of the cows, which, therefore, was also called mál in Iceland; maal in Danish; mål in the Ferroe Isles; meal in the North of England (the appointed time when a cow is milked, according to Brocketts Glossary of North Country Words 1825 p. 136; cf. the Craven Dialect, Lond. 1821 p. 92). |

| 167.1 | Arntz in his Account of Söndfiord in the Norwegian Topographical Journal 33 Nr. 1808, p. 13. See also Nr. 29, 1802, p. 37. |

| 168.1 | Björn Haldorson, Lexicon Islandico Latino-Danicum, Hafniæ, 1814. In this work, which otherwise is very valuable, especially as regards the modern Icelandic, the daymarks hirðisrismál, dagmál, náttmál are incorrectly explained; while the important word eyktarstaðr is entirely omitted. |

| 173.1 | Codex juris Islandorum, qui vocatur Grágás, Pars II. Hafniæ 1829, 4to, p. 221. |

| 174.1 | Lögbók Íslendínga, hvöria samansett hefir Magnús konúngr, Hólum 1709, 8vo, p. 230. |

| 174.2 | Den Islandske Lov Jonsbogen, udgiven af Kong Magnus Lagabæter (oversat ved Provst Egil Thorhalleson). Kjöbenhavn 1763, 8vo, p. 181. |

| 177.1 | Kristinrèttr Þorláks ok Ketils, s. Jus ecclesiasticum Islandiæ vetus. Hafniæ, 1776, 8vo, p. 92, 93. |

| 178.1 | When reference is made to the length of the day, the word staðr, at the place fixed for a daymark, if the time be morning, shows the rising of the sun in or nearest the beginning of the aliquot portion of time indicated by it; but if the time be evening, it shews its setting near another daymark, which indicates the termination of the hour, or also of the day or diurnal course of the sun; for example, dagmálstaðr, and eyktarstaðr, Ant. Am. p. 32. |

| 179.1 | See Snorra-Edda ásamt Skáldu, ed. R. Rask, Stockholm 1818, p. 188. |

| 180.1 | Heiðarvíga Sögu brot in Islendínga Sögur |

| 180.2 | See Finni Johannæi Hist. Ecclesiast. Island. T. 1 p. 150–156. |

| 181.1 | In the ancient Icelandic work, called Rímbegla, are given many rules for the measurement of time, for the study of Astronomy, Geometry etc., which, no doubt, seem to have been translated and compiled from foreign works, but which nevertheless correspond with what the clergy of the North immediately after the introduction of Christianity taught their pupils, who were partly designed for ecclesiastical and partly for temporal employments. Among these are found scientific rules and computations for finding the course of the sun, moon and stars, also the division of time thereon depending; information respecting the astronomical quadrant and its proper use; different methods of ascertaining the spherical figure of the earth; the longitude and latitude of places, and of calculating their distance from each other; the sun’s declination; the earth’s magnitude and circumference; the times when the ocean could best be navigated, etc. |

| 181.2 | Thus, early in the 11th century (about 1018–1028) the rich chieftain Raudulf of Österdal in Norway, taught his son Sigurd the science of computing the course of the sun and moon and other visible celestial bodies, and particularly to know the stars, {182} which mark the lapse of time, that he might be able to know what time it was by day and by night, even if he could not see either sun or moon. See Fornmanna Sögur V. 334–335; Scripta Historica Islandorum V. 310–59. Even belonging to the period strictly heathen we have similar accounts of Icelandic chieftains and their sons, nay even of simple peasants, who paid sedulous attention to the motions of the heavenly bodies, in order from thence to find out the true lapse of time; also of their belief in Astrology, which was intimately connected with the Old-Northern Mythology. We cannot in this place develope this subject further, but we have in some measure done this in other writings. Here we shall merely add a remark from Olaus Magnus (Lib. I. Cap. 34), that in his time (about 1520) it was generally acknowledged in Sweden, that the common people in ancient times had more knowledge of the stars than they possessed in his days. |

| 182.1 | In several literary Journals the Northern discoverers of America have lately been called Pirates (Vikings). This they certainly by no means were, but on the contrary all their leaders were Merchants, and at the same time Shipowners (as, for example, Biarne HerlulfsonPresumably misprint for Heriulfson, Leif, Thorfinn, Helge, Finnboge, Biarne Grimulfson, Thorhall Gamlason). Their ships were called kaupskip, trading vessels. Neither is it a correct assertion that these men roamed about without aim or object. All of them had fixed objects in view in their voyages of discovery, although the first mentioned had not for his object to discover (to search for) America, but on the contrary Greenland, in order to spend the winter with {183} his father, who had removed thither, with whom he actually did establish his residence. Thorfinn and his 160 companions intended to colonize Vineland, on which account they carried with them cattle. |

| 183.1 | See Konúngs Skuggsio, Sorö 1768, 4to, p. 17-236. |

| 184.1 | Probably in Old-Saxon ekt or ett, (whence etti, intervalla, in a very ancient glossary contained in Graffs Diutiska). In Bavaria, according to Schmeller, the common people still say eicht for Weile, Stunde; and eichtlein (perhaps a half eikt) for a short Stunde. |

| 185.1 | MS. in the Library of the R. S. N. A.Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries (Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab), Copenhagen |