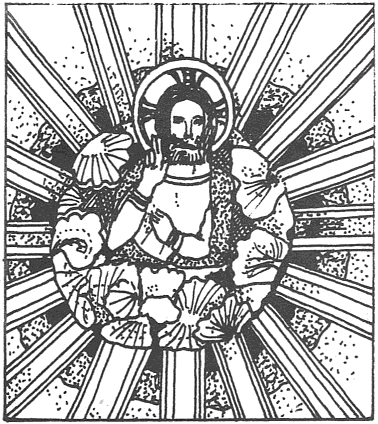

John Burwell’s woodcarving of Christ which marks the centre from which the sacred geometry of “Ad Quadratum” and “Ad Triangulum” are derived – God, the centre of all.

Journal of Geomancy vol. 1 no. 1, October 1976

{17}

The cathedral city of Ely surmounts a small rise in the formerly impassable fenlands, still titled the Isle of Ely. The City, in reality a small town, owes its existence to the cathedral, once a mighty and important monastic establishment, now frequented more by tourists than worshippers. Despite this near cessation of the practice of Christian worship, the Cathedral still dominates the flat landscape of the fens.

One thousand three hundred years ago, Æthelthryth (Etheldreda), daughter of King Anna of East Anglia, founded the monastery. Although married twice, she had made a vow of virginity, and kept it. In the twelfth year of her second marriage, she entered the monastery of Coldingham in Berwickshire. When her husband attacked the monastery with the intention of getting her back, Æthelthryth fled to Ely, her journey being punctuated by several miracles. On the way, at Altham, her staff, thrust into the ground for the night, took leaf, becoming in later years a mighty ash tree, the greatest tree in all that country. The place later became known as Etheldredestow, and is crying out to be geomantically analyzed.

Arriving at Ely, she fixed the site of her future monastery at Cradendune, about a mile south of the present site, where there had formerly been a Roman church. However, this was for some reason unsuitable, and the site was moved northwards to the site where the present cathedral stands. In 673, the monastery began to function. When Æthelthryth died in 679, the brethren of the monastery (which was for both monks and nuns) went out to seek a block of stone for a shrine. In the ruins of Roman Grantchester (the Armeswerk at Cambridge), a Roman marble coffin was found by divination.

From early times, like Glastonbury, the island of Ely (etymologically supposed to be the island of Eels) possessed a religious aura. Site of a Roman church, it became, on the death of Æthelthryth the site of a great religious fair, St. Audrey’s (October 17th), from whence the word Tawdry, describing the shoddy trinkets sold at the fair, is derived. The Danish Army, in 870, destroyed the monastery, although a small band of secular clergy soon re-occupied the site. A century later, Athelwold, bishop of Winchester, purchased the whole district of Ely from King Edgar, and founded the Benedictine Abbey. The Benedictines were the major order connected with the geomantic founding of Abbeys in Bohemia, (ref. 1) and operated Glastonbury, the other end of the vesica discovered by Michael Behrend (ref. 2). From the reign of Ethelred to the Conquest, the Abbots of Ely were Chancellors of the King’s Court alternately with the Abbots of Glastonbury and St. Augustine’s Canterbury, each holding office 4 months of the year.

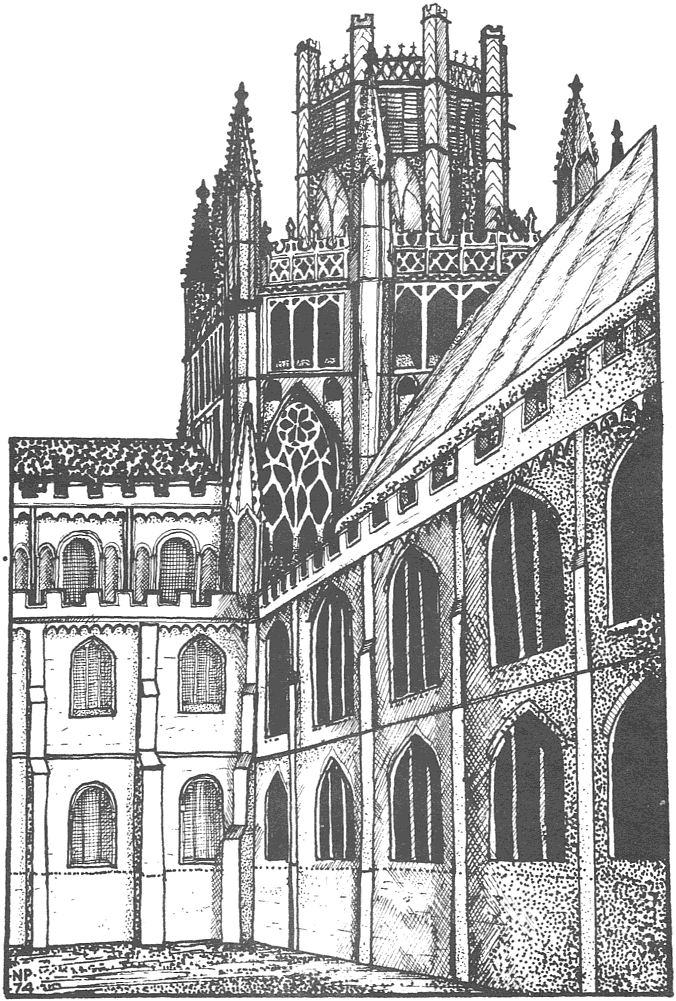

At the Conquest, Ely held out against the Normans for five years under the leadership of Hereward the Wake. The last Saxon Abbot of Ely died a year later, in 1072. The present Cathedral was laid out under the rule of Simeon, first Norman Abbot, in 1082. When it was partly built, in about 1100, St. Etheldreda’s body was translated from the still-standing Saxon church into the new Norman edifice. The site of the Saxon church has not been determined with any accuracy, although the partially-completed nature of the new Cathedral points to its having been demolished in order that the new building could occupy its space. {18} The Cathedral was originally designed to terminate in a rounded apse; however, this was squared off in 1103–6. There was a central tower, and, at the west end, a single tower with four flanking turrets. This westwork later influenced the church of St. Mary, Stralsund. The building was finally completed in about 1180.

In the 13th Century, a Galilee was added, in the same position as at Durham and Glastonbury. The parallels with Glastonbury constantly recur, being the building geomantically linked with Ely. An eastward extension of the chancel was made, as at many English churches, costing £5040. This extension was according to the system of “Ad quadratum” with which the basis of the Cathedral was laid out, an extension by one oblique square of Nave width plus a 45° triangle of vault width. This oblique square was later utilized to define the width of the Lady Chapel, begun in 1321.

John Burwell’s woodcarving of Christ which marks the centre from which the sacred geometry of “Ad Quadratum” and “Ad Triangulum” are derived – God, the centre of all.

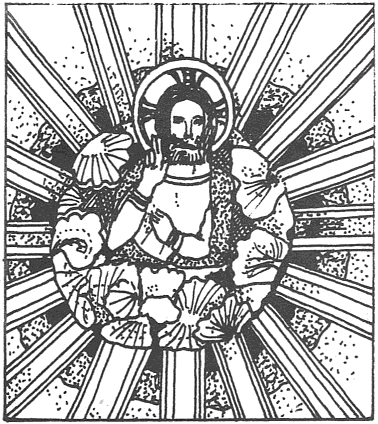

View of the wooden vaulting of the Ely octagon, designed by William Hurley, with central boss above the omphalos showing Christ in majesty.

Like its counterpart at Glastonbury, (ref. 3) Ely Cathedral is laid out according to a combination of the two Masonic systems of sacred geometry – “Ad quadratum” and “Ad triangulum”. The year after the Lady Chapel was begun, the central tower over the crossing omphalos fell down. It collapsed towards the east, perhaps weakened by the earlier reconstructions in that quarter, and demolished the western bays of the Norman choir.

Reconstruction commenced, and the original sacred geometry of “Ad quadratum” was adhered to. The tower was not rebuilt in its previous form, however, an “octagon” being erected in its place. The octagon’s technical method of construction is almost an exact copy of the system used in the mausoleum of Ilkhan Uljaitu at Sultanieh (1307–13). The Islamic octagon, itself derived from Classical antique architecture, was often incorporated in European building, after the crusades. This octagon was based upon the inner octagon projected around the omphalos, eight massive piers supporting an octagonal structure, completed in 1328. On top of this, a major work of English carpentry was designed and executed by William Hurley, the Royal Carpenter. Eight oaks of 63 feet (7 × 9) had to be found, with a sapless scantling of 3ft 4ins × 2ft 8ins. These vast oaks, the like of which no longer exist as living trees in England, were rare even in 1328, and were difficult to find. Inspection of the lantern to-day shows one of these angle-posts to be made of two shorter sections joined together. However, this may be due to later “restorations” (see below). Transportation of these trees from various parts of the realm proved a not insuperable problem, even with only ox-power and bad roads.

The eight angle-posts of the octagonal lantern are tied together at the bottom and at the top with collars of horizontal bracers, resting on the tips of inclined beams, whose lower ends are supported by corbels behind the capitals of the eight piers of the octagon.

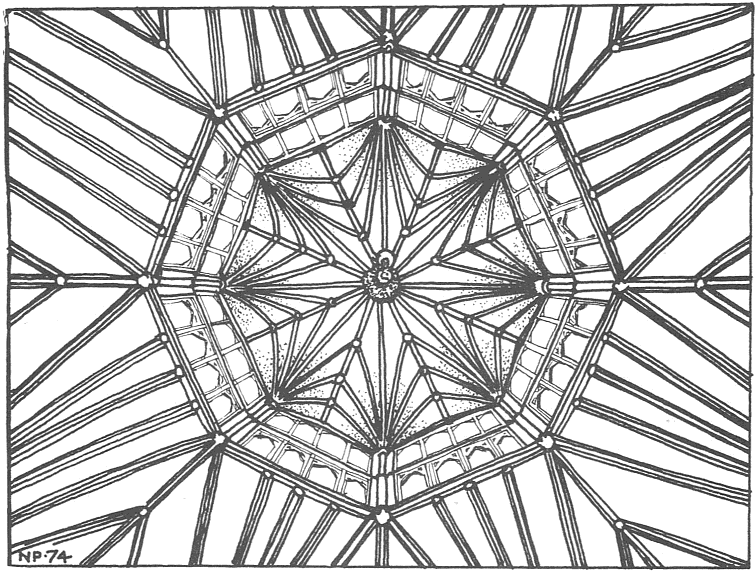

The exterior of the octagon tower (from a photograph of 1854) before its late 19th century reconstruction.

View from the north-west of the octagon in 1974, showing the late 19th century remodelling, with 1950s leadwork on the 8 uprights. The octagon is the landmark, visible from many miles, which expresses the importance of the omphalos.

This unique lantern was vandalized by the architect James Essex in the eighteenth century. Essex removed the external supports (the spire was destroyed earlier), reduced the windows in size, and generally ruined it. In 1860, another “restoration” took place, the lantern receiving its present appearance. (see illustrations; 1854 and 1974).

At the same time as the chancel and tower were being rebuilt, construction of the Lady Chapel was in progress. The size of this Chapel is determined by the two Masonic geometrical systems. The west end wall is in line with the east end wall of the transepts, and extends northwards as far as the point where an extension of the oblique square on the circle defining the transept size crosses this line. {19} The dimensions of the Lady Chapel are defined by a circle whose radius is r = a little less than 105 feet (the same as the basic radius defining the octagon), based upon the northeast vertex of the “Ad Triangulum” hexagram. The internal corner on the northeast is produced by a curved triangle, radius r, and the northwest corner also. The diagonal line defining the cathedral’s east end meets the north west corner of the Lady Chapel after passing thru the door into the chapel. A radius from the omphalos touching the end buttresses of the Lady Chapel touches the end buttresses of the east end of the Cathedral, as well as the centre-point of the western octagram, being 2r = 210 feet.

r is evidently 96 Saxon feet of 33·5cm, a number mystically linked with the 8-fold nature of “Ad Quadratum” 12 × 8, just as the number 288 feet = 96yards was used in King’s College Chapel. The internal length of King’s Chapel is 1/3 of 500 Royal Cubits, whilst Ely’s length is 300, a ratio of 5:9. One recurring fact is that many sacred building are so arranged as to incorporate significant dimensions in several units. (ref. 4).

Inside this large circle of radius 2r, the circle encompassing the Lady Chapel is drawn. Internally, the Cathedral is 517 English feet in length. This corresponds to 470 Saxon feet, 628 Welsh feet, 533 Roman feet and 300 Royal Egyptian Cubits, (a measure found by Hugh Capstick in Salisbury Cathedral).

The ground plan is fundamentally unchanged from mediaeval times, unlike the superstructure. During the middle ages or reformation, the parish church of St. Cross (the Holy Cross) was demolished. (1 on plan) This had been constructed upon the dimensions of part of the parallel square of the western octagram. The north-west transept and its accompanying towers was demolished also at some unspecified time. The south-west transept remains ostensibly Norman architecture. However scrutiny of Harris’s Plan “The Ichnography of the Cathedral Church of Ely”, which depicts the layout before the eighteenth century, shows no apse on the southwest transept. In the eighteenth century, that part was known as the South Galilee, and was the church workhouse. It must therefore be concluded that the apse is nineteenth-century addition.

This combination of “Ad Quadratum” and “Ad Triangulum” has also been found by the author to occur at Glastonbury Abbey. At Ely, the predominant system is “Ad Quadratum”, exemplified by the octagon. Eight is symbolic in Christian numerology of the New Covenant and Salvation, Christ having risen, in Christian mythology, on the eighth day of the week, there being 8 benedictions on the Sermon on the Mount, and the 8 saved from the Flood.

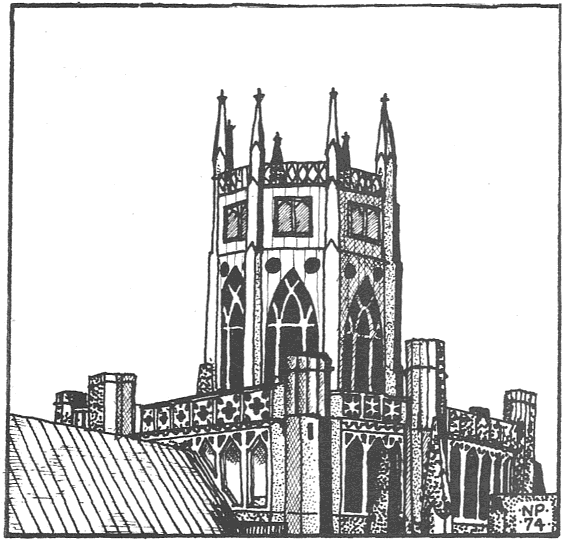

The octagon occurs at Ely Cathedral also in the West tower, where the upper part is octagonal, flanked by four small subsidiary towers, the formal layout found in domed ‘Ad Quadratum’ structures, such as Byzantine and Russian Orthodox churches and Islamic mosques. Flanking this central tower were 4 small towers, making 9 in all. This 9 is said to represent the nine hierarchies of angels (or devils!).

This symbolism occurs thruout Gothic architecture from the smallest item to the layout of towns such as Glastonbury and Cambridge. (refs. 5 & 6.) Such is the completeness of destruction of the concepts behind the system that many churchmen today deny the symbolism, the geometry or even dismiss as evil the geomantic layout of the churches. The suppression of this knowledge was the result of the so-called ‘renaissance’, where other systems, derived in the main from Classical antiquity, were imposed in place of those practised by the masons, with the inevitable consequence of a loss in continuity. {20}

Gothic knowledge survived with operative masons well into the 18th century, with Köln (Cologne) and Wien (Vienna) having operative lodges until 1707 and Strasbourg until 1771. However, in England, the destruction of the monasteries in 1539 effectively damaged the masonic lodges to an irreparable degree, and vandalism and demolition proceeded apace. The masons were reduced to working on scanty repairs and small-scale projects, whilst Vitruvian ‘Architects’ took over construction of churches, using Greek and Roman models. Occasionally, though, combined systems occurred, the most notable example being Wren’s St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, itself based on Ely Cathedral, where his uncle had been bishop and where Wren had rebuilt the western corner of the north transept after an earthquake in 1699.

A long term project of the author is analyzing the ground-plans of English Cathedrals, which will be published in future editions of the Journal of Geomancy.

1. Kurt Gerlach: Frühdeutsche Landmessungen (1940) and “Heilige” oder Zweckmässige Linien über Böhmen (1942). Trans. M. Behrend and P. Jones in Central European Geomancy. (IGR Occasional Paper No. 3).

2. Michael Behrend: (unpublished communication).

3. Nigel Pennick: The Geomancy of Glastonbury Abbey. (Megalithic Visions Antiquarian Papers No. 11, Fenris-Wolf 1976).

4. Ian P. Worden: The Round Church of Orphir, Orkney. (IGR Occasional Paper No. 6). In press.

5. Nigel Pennick: The Mysteries of King’s College Chapel. (Cokaygne 1974).

6. Michael Behrend: Cambridge: The Hidden City. (unpublished).