Translated from “‘Richt’-Linien durch Deutschland”,

Germanien, 1943, 27–33.

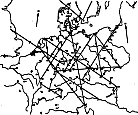

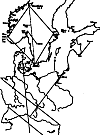

This is Gerlach’s final paper in Germanien on his landscape-geometry theories. Here he extends the system of lines from Bohemia to England and Scandinavia. These “guidelines” (richtlinien) fall into groups of parallel lines labelled A, B, C, etc. The article ends with another bit of propagnda.

The notes at the end, relating to the two maps, are repeated in this Web version as captions to the maps.

„Richt“-Linien durch Deutschland

In the following the term “guidelines” (richtlinien) will be used for what have hitherto appeared in the literature as “holy lines” (heilige linien), because here we shall concentrate on the practical use of these alinements – that being obviously the main reason for their existence, though it can in a sense be described as a sacred one. Among the many possible instances that have come to light, we shall cite a number which can be supported from documents and literary authorities with the year they are first mentioned and the name of their organizer or surveyor – which is not to say that this surveyor was the first, or that the year in question is the original year of construction. However, it seems that we are dealing with a universal custom, by which every high spot or conspicuous elevation on German soil required the following: a panoramic view over the landscape; the finding of one’s way within it; the observation of the place from which one had come and the place where one wished to go, with the aid of certain well-defined points, for which purpose sunrise and sunset would be used if possible even today, if other means of finding direction, eg the compass and sextant, were unknown. That at an early stage the division of the distant horizon and the location of markpoints might have been achieved by means of a wheel (such as the spoked wheel of an overturned wagon) must remain a conjecture, as long as we have no further evidence than the mention in Shakespeare (Ref. 8) and the fact that from time immemorial the wheel has symbolized the law and used to be found at every place of execution.

Lines in Bohemia have been measured mainly on 1:200 000 maps, occasionally on 1:75 000; and in Saxony on the official map at 1:100 000 and surveyors’ maps at 1:25 000. But when on comparing maps (even official ones) it turns out that two neighbouring sheets, at say 1:100 000 scale, disagree by over 5 mm, one can easily judge the limitations of mapwork.

Nevertheless such a guiding system was perfectly adequate for purposes of long-distance communication and travelling; and bands of migrating people (such as the crusades into the Holy Land), or missionary journeys, or merchants’ caravans, could have been directed along it, just as these long-distance alinements made it possible to govern such a large empire as the Carolingian. It is hard to imagine what it means when Charlemagne, for instance, called sixteen imperial parliaments during his reign: how first the messengers, then the bishops and counts with their retinues, had to travel to and fro far across the country. Or what administrative work, what a coming and going of messengers, how many journeys by foot, horseback and wagon were needed in a diocese such as Salzburg, which owned over sixteen hundred properties. Since fiscal and administrative affairs in the Middle Ages were largely in the hands of the Church, we shall here describe a number of straight alinements linking important church foundations in an “oriented” way.

Line A1: York/Utrecht/Amöneberg/Fulda

According to Hauck (Ref. 5) it was by chance that the Frisian people attracted the attention of the English clergy. In 678

the quarrelsome archbishop Wilfred of York was trying to escape to Rome, and is supposed to have been driven onto the

Frisian coast. At any rate that is what the sources say. Then Wictberct worked in Frisia, and in 690 Willibrord landed

with twelve men at the mouth of the Rhine and took himself to Utrecht. The Frisian duke Radbod was conquered by Pipin.

Willibrord went to Pipin and requested permission and support for his work. The Anglo-Saxons chose their own Frisian

bishop, but Pipin himself settled the matter and decided to have an archbishopric in Frisia. In 695 Willibrord was

consecrated in Rome as archbishop of Frisia and went to Utrecht. There a church and a Benedictine monastery were

founded. This line was lengthened, first apparently by the Anglo-Saxon Wynfrith (alias Boniface) when he founded

Amöneberg monastery on a basalt cliff near Marburg, then by Wynfrith’s Bavarian pupil, Sturm, who built Fulda

in 744. The circumstances are remarkable, so we shall quote them from Hauck (Ref. 6): “Then he (Boniface) agreed that

Sturm, after his consecration as priest, should spend three years in the Buchonian forest seeking a suitable place for a

retreat. He found it where the Haune and Geis flow into the Fulda, the site where Hersefeld monastery was later built.

Sturm lived there with two companions. But the cell did not immediately become a monastery; Boniface had it in mind to

found a monastery there, but the nearness of the heathen Saxons seemed a threat to its survival. He instructed Sturm to

look for a protected spot further to the south. Sturm made many a fruitless journey in the wooded valleys in the

foothills of the Rhön and Vogelsberg ranges. Finally it seemed to him that a place called Eichloh suited all

requirements.” The village was in the possession of Karlmann. Karlmann granted the monastery a site eight thousand

paces in diameter. Sturm arrived at Eichloh on 12th March 744 with seven brothers from Fritzlar; in May Boniface came to

consecrate it. The monastery was placed under Roman rule, an unprecedented step in the Frankish church.

According to Hauck (Ref. 5) it was by chance that the Frisian people attracted the attention of the English clergy. In 678

the quarrelsome archbishop Wilfred of York was trying to escape to Rome, and is supposed to have been driven onto the

Frisian coast. At any rate that is what the sources say. Then Wictberct worked in Frisia, and in 690 Willibrord landed

with twelve men at the mouth of the Rhine and took himself to Utrecht. The Frisian duke Radbod was conquered by Pipin.

Willibrord went to Pipin and requested permission and support for his work. The Anglo-Saxons chose their own Frisian

bishop, but Pipin himself settled the matter and decided to have an archbishopric in Frisia. In 695 Willibrord was

consecrated in Rome as archbishop of Frisia and went to Utrecht. There a church and a Benedictine monastery were

founded. This line was lengthened, first apparently by the Anglo-Saxon Wynfrith (alias Boniface) when he founded

Amöneberg monastery on a basalt cliff near Marburg, then by Wynfrith’s Bavarian pupil, Sturm, who built Fulda

in 744. The circumstances are remarkable, so we shall quote them from Hauck (Ref. 6): “Then he (Boniface) agreed that

Sturm, after his consecration as priest, should spend three years in the Buchonian forest seeking a suitable place for a

retreat. He found it where the Haune and Geis flow into the Fulda, the site where Hersefeld monastery was later built.

Sturm lived there with two companions. But the cell did not immediately become a monastery; Boniface had it in mind to

found a monastery there, but the nearness of the heathen Saxons seemed a threat to its survival. He instructed Sturm to

look for a protected spot further to the south. Sturm made many a fruitless journey in the wooded valleys in the

foothills of the Rhön and Vogelsberg ranges. Finally it seemed to him that a place called Eichloh suited all

requirements.” The village was in the possession of Karlmann. Karlmann granted the monastery a site eight thousand

paces in diameter. Sturm arrived at Eichloh on 12th March 744 with seven brothers from Fritzlar; in May Boniface came to

consecrate it. The monastery was placed under Roman rule, an unprecedented step in the Frankish church.

Line A2: Worms/Salzburg/Ptuj

In 696 Hrodbert (Rupert), bishop of Worms, having been summoned by the Bavarian duke Theodo, founded the church of St Peter and St Paul on what later became the site of Salzburg. “He worked in Bavaria, not as a foreign bishop coming to organize, but as a wandering bishop seeking a home and a mission. He met the duke in Regensburg, but did not remain in the Bavarian capital. … Hrodbert looked further down the Danube; he reached as far as the ruins of the old Roman town Laureacum (Lorch). Then he turned along the Traun up into the mountains. Thus he reached the lakes of the Salzkammergut. … Here he was needed and here he resolved to stay. His first foundation was St Peter’s church on the south bank of the little Wallersee, around which the village of Seekirchen soon grew up. Then he turned his attention towards Juvarum (Salzburg). Of the former Roman city there remained nothing but ruins, overgrown by the forest, but the site was not completely deserted; there was even a duke’s castle on the hill later known as the Nonnenberg.” The duke granted him the village and castle and the pasture belonging to it. Hrodbert was a distinguished man and related to the Merovingian house. In 874 the archbishop of Salzburg consecrated a church in Ptuj.

Line A3: Dokkum/Minden/Zeitz/Prague/Sázava/Rajhrad/Nitra/Vac

In 968 Otto I founded the archdiocese of Magdeburg and placed under it the newly- founded dioceses of Brandenburg, Havelberg, Merseburg, Zeitz and Meissen. Then in 973 the diocese of Prague was founded; in 993 Vojtěch, the second bishop of Prague, a descendant of the Slavnikovec family and related on his mother’s side to the Saxon royal house, built Břevnov monastery a short distance southwest of Prague; it had a priory in Rajhrad. The stage Rajhrad–Prague is the same length as the stage Prague–Zeitz. It may be remarked that according to the Bohemian chronicle by Cosmas, archdeacon of Prague, the sacred hill on the Prague citadel bore the name “Zizi” (Ref. 1). But as early as 836 the first church in Moravia had been founded on this line at Nitra southeast of Rajhrad. A second one came into being on the hill Skalka not far from Trenčín in the same year. In 880 Methodius, whose bishop’s see was at Uherske Hradiště, saw his worst enemy, the German Wichin, installed as his suffragan in Nitra.

In 1032 Duke Břetislav I founded Sázava monastery on this line, in a bend of the river Sázava at 44 km from Prague. Beyond Zeitz on this line we have still the diocese of Minden, consecrated by Louis the Pious, where however Charlemagne had founded a church in 803. The endpoint of the line A3 is formed by Dokkum. There must have been an important Frisian ritual and administrative centre at Dokkum, for Wynfrith (Boniface) summoned the baptized Frisians to be confirmed there in 754, and there he was killed near the river Borne.

Line A4: *Attigny/Basel/Chur

“The death bond of Attigny linked the bishoprics of Basel and Chur with the imperial episcopate” (Ref. 3).

*Tr: A mistake. The reference is to a council in the town of Attigny in 765, but Gerlach draws his line through a small village of the same name in the Vosges.

Line B1: Würzburg/Erfurt/Brandenburg

In 741 Wynfrith founded the dioceses of Würzburg and Erfurt. In 968 Otto I extended the line to Brandenburg.

Line B2 is given by Wynfrith’s first monastery at Amöneberg and his see at Mainz.

Line B3: Bremen/Osnabrück/Köln/Verdun-sur-Meuse

In 787 the diocese of Bremen, founded by Charlemagne, was placed under Bishop Willehad, who was consecrated in Worms. The Saxon dioceses of Minden, Münster, Bremen and Onabrück belonged to the archdiocese of Köln. The line Bremen–Köln cuts through Osnabrück, and extended beyond Köln meets the see of Verdun.

Line B4: Toul/Trier/Minden/Hamburg/Oldenburg in Holstein

After Charlemagne’s victory over the Saxons “the land north of the Elbe was also added to the Saxon missionary area. The work there was given to the diocese of Trier. Bishop Amalar built the first church in this region; it stood in Hamburg” (Ref. 7). The line also cuts the see of Toul.

Line B5: Bamberg/Zeitz/Kołobrzeg

This line was drawn in 1007 when the diocese of Bamberg was founded. Bamberg was given by Otto III to the father of Heinrich II, Heinrich of Bavaria. Kołobrzeg was a diocese by 1000 and was placed under the archdiocese of Gniezno.

Line B6: Niederalteich/Rinchnach/Prague/Głogow/Poznań/Tenkitten

The southwest portion of this line is the work of the hermit Günther, a descendant of the Thuringian counts von

Schwartzburg. After a journey to Rome he became in 1008 a Benedictine lay brother at Niederalteich on the Danube. He

founded Rinchnach and afterwards a cell at Hartmanice on St Günther’s Hill. Rinchnach lies 27·5 km

from Niederalteich, and the cell on St Günther’s Hill the same distance from Rinchnach, on the line from

Niederalteich to Prague.

Frind (Ref. 4) says of Günther: “With untold labour he built the so-called Golden Trail

through the trackless mountains around Prachatice.” After Günther’s death Duke Břetislav buried

the hermit’s body in Břevnov abbey, founded by Vojtěch.This Vojtěch, educated in Magdeburg,

resigned as bishop of Prague in order to travel to St Benedict’s foundation Monte Cassino and to Rome; then a

second time to travel via Poznań as a missionary in Prussia. At Tenkitten in Samland he was killed in 997. The line

B6 ends at Tenkitten.

Frind (Ref. 4) says of Günther: “With untold labour he built the so-called Golden Trail

through the trackless mountains around Prachatice.” After Günther’s death Duke Břetislav buried

the hermit’s body in Břevnov abbey, founded by Vojtěch.This Vojtěch, educated in Magdeburg,

resigned as bishop of Prague in order to travel to St Benedict’s foundation Monte Cassino and to Rome; then a

second time to travel via Poznań as a missionary in Prussia. At Tenkitten in Samland he was killed in 997. The line

B6 ends at Tenkitten.

Yet this region had been travelled before. In 965 the sister of Boleslav II of Bohemia, Dobrava, married the Polish prince Miesko, who was baptized in 967. Consequently in 968 the diocese of Poznań was set up by Emperor Otto I with German clergy. In 973 the diocese of Prague was founded.

Line B7: Rajhrad/Olomouc

In 1063 the diocese of Olomouc was founded.

Line B8: Pecs/Vac

In 1002 Stephen the Holy was crowned king of Hungary in Pecs. Pecs became a royal seat and a diocese, as Vac was already a diocese.

Line B9: Chełmno/Elblag

The later Baltic dioceses are the archdiocese of Riga, Tartu, Chełmno, and Elblag. Both Chełmno–Elblag and Riga–Tartu have the direction B. Riga became a diocese in 1202. The first church was built in 1184 at Ikskile on the river Duna.

Line C1: Worms/Würzburg/Bamberg/Teplá/Prague/Libice/Opatovice/Pěčín/Kraków

Line C1, set out from Prague, is marked by Opatovice as a cell of Břevnov, and later by Pěčín as a priory of Opatovice monastery. On this alinement lies Libice nad Cidlinou, the home town of Vojtěch, then Kraków which became a bishop’s see in 1000, subordinated to Gniezno along with Kołobrzeg, Poznań and Wrocław; then west of Prague the village of Krakov, reputedly at one time the home of Krok, the father of Libuše in Czech tradition. In 1193 the convent of Teplá was founded on the line C1. In addition it touches Bamberg, Würzburg and Worms, also perhaps Reims.

Line C2: Amöneberg/Erfurt/Zeitz/Meissen

Line C2 joins the bishoprics of Meissen and Zeitz, both founded in 968; then again Boniface’s foundations Erfurt and Amöneberg.

Direction C can also be established in other ways.

Line D1: Aarhus/Odense/Oldenburg/Magdeburg/Merseburg/Zeitz/Salzburg/Aquilèia

The longest line appears to be D1, which in the south is based on the Roman (later Carolingian) bishoprics at Aquileia and Salzburg. Both places were designated by Charlemagne as bases for the Saxon mission. In the middle of the empire, D1 was again marked out by Otto I at Zeitz, Merseburg, Magdeburg and Oldenburg in Holstein, all in the year 968.

Ansgar (died 865), a monk at Corbie and later at Corvey, who finally became archbishop of Hamburg, built two churches, in Schleswig and Ribe. The churches in Schleswig and Hamburg lie on the direction D. Under Svend Estridssen (died 1076) the Danish church was organized into eight dioceses: Lund, Roskilde, Odense, Schleswig, Ribe, Aarhus, Viborg and Bornholm. In 1104 Lund became the archdiocese for the northern territories. In 1152 Norway received an archbishop in Trondheim, and in 1164 Sweden one in Uppsala, though the archbishop of Lund remained Primate of Sweden (Ref. 2). Here corrections to lines A and B are noticeable, obviously imposed by the more northerly latitude. Nevertheless the lines Lund–Stavanger (diocese) and Uppsala–Trondheim are almost equal and run parallel to each other, proving that orientation and measurement were also practised in the north.

Line D2: Kołobrzeg/Legnickie Pole/Broumov/Pěčín/Rajhrad

Line D2 is clearly marked by priories that arose with the founding of Břevnov, and can thus at once be ascribed to Vojtěch. Priories of Břevnov included Rajhrad, Broumov, and Legnickie Pole in Silesia. In Broumov and Legnickie Pole there were later priories of Opatovice monastery. An extension of the straight line Rajhrad–Pěčín–Broumov–Legnickie Pole takes us to Ko#322;obrzeg, which was already a bishop’s see by the year 1000.

Line D3: Dokkum/Köln

The Frisian mission was attached to Köln. Wynfrith (Boniface) was originally to have been archbishop of Köln.

Line E1: Utrecht/Köln/Mainz/Aquilèia

Line E1 results from the dependence of Utrecht on Köln. Then Mainz was also linked by Boniface with Utrecht. When extended, this line ends at Aquilèia.

Line E2 is given by the stage Kraków–Kołobrzeg, drawn in the year 1000.

The examples given here are not a complete proof of orientation and measurement in Germany, but they are striking enough when taken with the author’s previous articles in Germanien. It should now be clear, for instance, how the peculiar unit of 11 km came into the Bohemian landscape, where it measures out long distances: it must embody the Lower Saxon or Frankish hour-measure, used all over the empire from the Carolingian period to the Staufers (1154–1254); the Dutch ure or the raste, which still gives its name to hills in the mid-German landscape called Urenberg or Rastenberg. The existence of this vast geometrical survey in early times shows us that there was more territory in central Europe occupied by the ancient Germans than has been conceded to us – the nation without room – in later times.

| 1. | Bachmann, A. Geschichte Böhmens, 1, 73. Gotha 1899. |

| 2. | Ekklesia II. Die Kirche in Dänemark, 21. Leipzig 1937. |

| 3. | Ekklesia III. Die evangelischen Kirchen der Schweiz, 19. Gotha 1935. |

| 4. | Frind. Kirchengeschichte von Böhmen, 4, 361. Prague 1864. |

| 5. | Hauck. Kirchengeschichte von Deutschland, 1, 431 (edns. 3 & 4). |

| 6. | Hauck. Kirchengeschichte von Deutschland, 1, 580. |

| 7. | Hauck. Kirchengeschichte von Deutschland, 2, 415. |

| 8. | Shakespeare. Hamlet 3.3.17. |